1. Zola’s early years

Zola was born in Paris in the spring of 1840. He spent much of his early life in southern France in the city of Aix-en-Provence, north of Marseille, where his father was working on the construction of a municipal water system.

His father, François Zola, was a Venetian engineer whose family had served in the army of the ancient Republic of Venice for generations. His father, Carlo Zolla, had been a captain in the engineers.

François, formerly Francesco, had followed the path of his family at first before deciding to follow his passion and study mathematics at the University of Padua. His career was diverse and impressive, including a role in planning the first public railway in Europe. He was responsible for establishing the fresh water supply for Aix and built the Zola Dam.

Zola’s mother, Émilie Aurélie Aubert, was French and the daughter of a seamstress and glazier. Her family had done fairly well for themselves after migrating to Paris from the rural area around the city in the early 1830s. However, they still lacked means. At the age of 20, she married François, who was 24 years her senior. Her parents could not offer much of a dowry, but François insisted that he would happily marry her for herself alone - he had fallen in love at first sight.

The family lived a fairly happy life, despite François’ struggles to find contracts for his engineering projects. He was cheerful and optimistic, certain that one of his ideas would come good. As a result, he continued to construct the life he wanted for his family, racking up enormous debts in the process.

When Émile was seven, just three months before the completion of work on the Aix-en-Provence project, François died of pleurisy. He had barely been ill throughout his entire life. Young Émile and his mother were left alone, straddled with enormous debts and in severe financial difficulty. Living on just 150 francs a month, whilst also supporting Émilie’s elderly parents, the carefree lifestyle the young family had had in the past was long gone.

In 1958, they moved permanently to Paris and Zola lived with his mother, either in the same house of very close by, until she died in 1880. Zola spent much of his youth in poverty, unemployed and working odd jobs where he could, pawning his belongings to get by during the worst times. He continued his hobby of writing fiction, which he had enjoyed since he was a boy, and spent much of his free time writing novels.

It was in 1864 that Zola met Gabrielle Alexandrine Meley. When Alexandrine began her romance with Zola, she was already an extremely tough and independent young woman. Alexandrine had been forced to fend for herself from childhood - her mother and father had been teenagers when they had her and were unmarried. Her father soon married someone else and her mother died of cholera.

As a result, Alexandrine was left without care. To survive, she trained as a ‘lingère’, a type of seamstress specialised in making, repairing and maintaining women’s undergarments and household linen.

Biographers have pieced together the story of Alexandrine and Zola’s marriage from letters and journal accounts of the time. What they have found is a tale of extreme drama and despair, on Alexandrine’s part.

Through the 1870s, after publishing his first novel, Zola experienced a sharp increase in popularity. His novels became bestsellers in France and abroad and for the first time in his life, he amassed a fortune. He and Alexandrine were able to live very comfortably, buying a house in Medan to the west of Paris, whilst keeping an apartment in Paris.

As a now bourgeois lady, Alexandrine hired a lingère to help her, as she had done for ladies in her youth. Jeanne Rozerot was just 21 when she met the Zolas. She did well in her role but she shortly resigned following a trip to Royan with the couple. Alexandrine did not have any further contact Rozerot. Unbeknownst to her, however, Zola arranged for her former servant to have an apartment close to their home and they began an intimate relationship.

By September 1889, Rozerot and Zola had their first child. A second child was born in 1891. In November 1981, Alexandrine received an anonymous letter telling her about their secret relationship and the children.

Her reaction was violent, her pain came out as physical destructive anger and she smashed the furniture in Rozerot’s home, swearing revenge. Zola had warned Rozerot to leave the flat before Alexandrine’s arrival as there was a significant danger that she could have been harmed in the process.

Despite the deep sense of betrayal, loss, shame and despair experienced during this time, Alexandrine eventually decided upon a new arrangement. She took control of her husband’s affairs, making contact with his children and establishing a relationship with them, albeit keeping them always at arm’s length. It was agreed that wherever they travelled, Jeanne and the children would accompany them. For the rest of his life, Zola divided his time between his wife and his second family.

2. Zola’s writing

The experiences of Zola’s childhood and romances would become one of the foundations of his writing career.

Zola was a champion of the ordinary French people and his writing frequently featured characters who he would have met through his early years. It is possible to trace some of Zola’s life experiences through his books, from the passionate but forbidden romance of ‘Doctor Pascal’ to the poverty and hunger of Florian in ‘The Belly of Paris’.

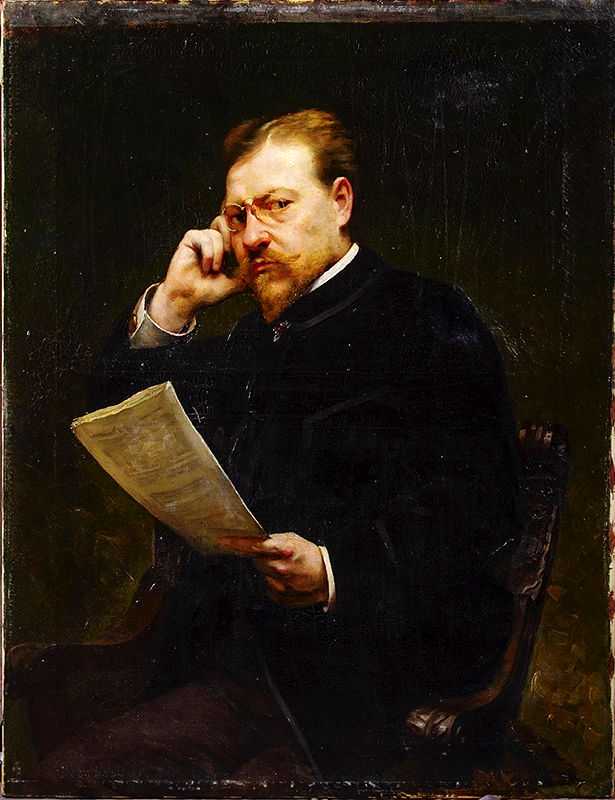

Zola first began writing as a way of supporting himself, writing articles for different periodicals. At the same time, he started a novel in his free time, which was eventually finished and published in 1865. The semi-autobiographical tale ‘La Confession de Claud’ was so sordid that it drew the attention of the police as well as the public, creating outrage among Zola’s employers at the time.

This first novel provided Zola with enough income to support him and his mother and he decided to become a freelance journalist. His next book was ‘Thérèse Raquin’, written in 1867.

This would become one of his most famous novels, still widely read today. In Thérèse Raquin, a tale of murder and regret, Zola’s painterly eye is clearly evident. His descriptions are colour-focussed and rich in visual description. Like all of his novels, it combines motion with vivid imagery to create an intense portrait of modern industrial society.

Perhaps Zola’s most notable literary contribution, however, was his ambitious project known as the ‘Rougon-Macquart’ series. This series, which began in 1870, totalled 20 volumes by the end of Zola’s career.

He completed roughly one per year and the novels intertwined and crisscrossed between different generations and relations of one family. In doing so, Zola mapped out the life of the working classes and lower middle classes of Paris, examining with an almost scientific lens the social, sexual and moral landscape of his time. Consequently, he penned a notable historical as well as literary resource for future readers.

In particular, Zola developed views on Naturalism, theorising on the use of scientific method to create characters in fiction. He believed in showing all aspects of life, including those that are ugly and unpleasant, taking a more extreme approach to the literary Realism that had come before. In conjunction, Zola often used animal imagery to depict humanity’s most bestial urges.

It was Zola’s combination of visual detail and movement that has led critics to name him as an important forerunner of the motion picture. Indeed, a number of his novels have shown themselves to be well-suited to adaptation into films.

3. Zola and the Impressionists

Zola’s early bohemian lifestyle inevitably led him towards the artistic community of Paris in the late 19th century, including the first Impressionist artists.

Throughout his life, Zola’s story interweaves with that of the Impressionist movement. He was one of the most closely connected French writers when it came to painters and artists.

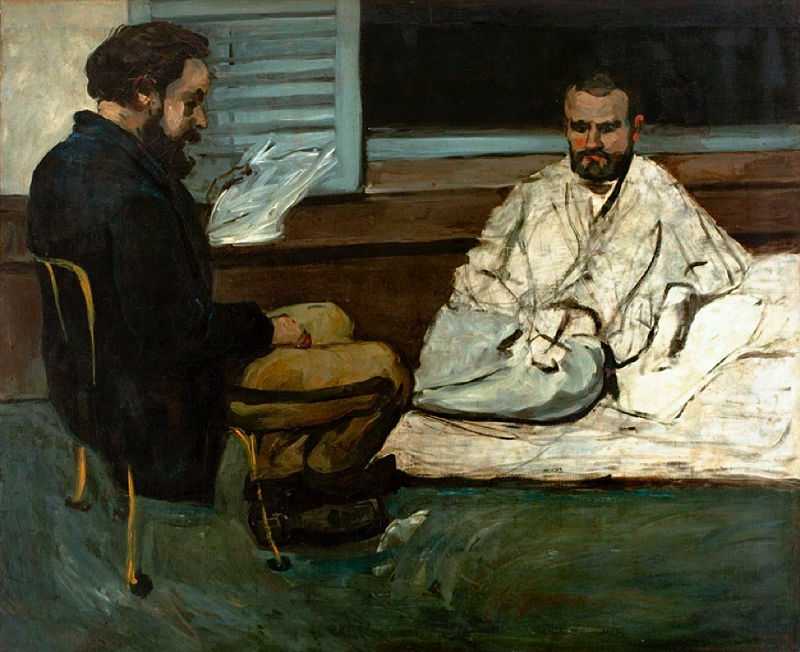

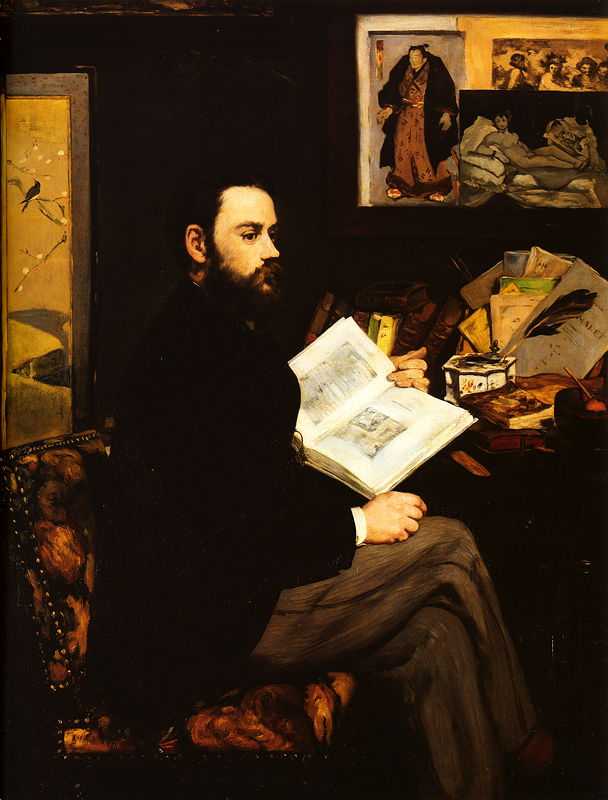

The foundation for these relationships began at a young age. When he was just a student in Aix, Zola was classmates with Paul Cézanne. This connection continued in Paris, where Cézanne introduced Zola to Impressionist painters like Édouard Manet.

Later, in the 1860s, he wrote articles on the work of the early Impressionists, including Claude Monet, Frédéric Bazille, Edgar Degas and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. He heavily defended their work in his writing, becoming close friends of many painters in the studios and cafes of Paris. He further organised evening gatherings at his large country home from 1866 onwards. In these informal gatherings, art theory was frequently discussed and debated.

The Impressionists served as a great source of creative inspiration for Zola, with Cézanne being the most prominent. In ‘The Belly of Paris’ from 1873 this influence is evident in Zola’s painterly descriptions of the markets of Les Halles in Paris.

His rich descriptions of the food on display and the colours and textures therein demonstrates his exposure to an artist’s perspective of the ordinary world. The character of Claude Lantier is said to have been based on Cézanne, from the detailed description of his appearance to his struggles with his creative ego.

Like many Impressionist artists in the late 19th and early 20th century, Zola also began experimenting with photography. He became highly accomplished in the art of photography, taking thousands of photographs that he would develop in the basements of his three homes. In doing so, he also mastered the chemical processes involved in photography and even experimented with making his own contact sheets.

It was in 1886 that Zola’s relationship with the Impressionists was dramatically severed, however, following the publication of Zola’s novel ‘L’Oeuvre’ or ‘The Masterpiece’.

The story follows the life of an accomplished painter who is unable to realise his full potential and so is driven to hang himself in front of his masterpiece. The Impressionists were shocked by the brutal portrayal of the artistic temperament and Cézanne in particular saw the novel as a personal criticism, jibing at both his character and his talent.

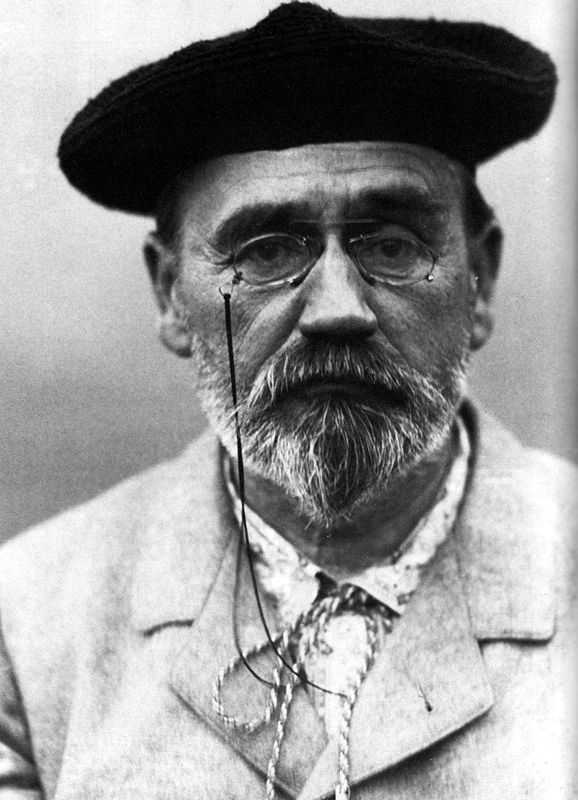

Though Zola and the Impressionists went their separate ways, their paths crossed once more during the Dreyfus Affair, which would come to be a defining moment in Zola’s life and career. In 1898, Alfred Dreyfus, a French Jewish army officer, was convicted of treason. The controversy surrounding the case continued for another 12 years, becoming a defining and divisive moment in French society.

Early on in the proceedings, Zola correctly deduced that Dreyfus was innocent. He published an open letter in L’Aurore newspaper in 1898, vehemently denouncing the War Office and many high-ranking military officers for their injustice. This letter has now become known by its first two words: “J’accuse” or “I accuse”.

The event divided the artistic community of Paris. Monet and Pissarro, who was also Jewish, sided with Zola and were staunchly pro-Dreyfus. Monet wrote to Zola following the publication of “J’accuse” to congratulate him on his courage. However, many more artists including Mary Cassatt, Cézanne, Renoir and Degas were staunchly anti-Dreyfus. Both Renoir and Degas were openly anti-Semitic and Renoir spoke out against his old friend Pissarro, protesting against having his work shown alongside that of a Jew.

Of all the Impressionists, Degas was by far the most anti-Semitic, however. In the years following the Dreyfus affair, he cut all ties with his boyhood friend, Ludovic Halévy, who was from a Jewish family. He only returned to his home briefly to pay his respects after his death. Degas further shunned fellow Impressionist Pissarro, dismissing his works as unworthy and ignoble, when once he had praised his works highly.

For his intervention in the Dreyfus affair, Zola was found guilty of libel and he fled to England in 1899. He returned to France the following summer as the Dreyfus case was being reopened. By speaking up about the affair, Zola helped to undermine French nationalism, militarism and anti-Semitism, encouraging scrutiny of the French military and swaying public opinion.

4. Zola’s legacy

The death of the author death was as filled with drama as his life. On the 28th September 1902, he and Alexandrine returned to their home after a visit to the country.

A smokeless coal fire was lit in their bedroom and they slept with the window shut and the door locked, as Zola was still receiving death threats over his denouncement of the Dreyfus affair. Over the following hours of the night, they were slowly overcome by carbon monoxide fumes from the fire. At 3am, both were awake and feeling sick but Zola prevented Alexandrine from waking the servants as he assumed it was just indigestion.

The following morning, Zola was found dead on the floor of the bedroom. Alexandrine was unconscious in bed. She later recovered in a clinic and sent word to Rozerot of what had happened.

Rozerot’s immediate assumption was that Zola had been murdered and indeed, a later inquest and tests done on the room showed little sign of carbon monoxide. Two guinea pigs placed in the sealed room survived. To avoid public upset, the report from the inquest omitted the details that would suggest Zola’s death had been unnatural.

Much later, in 1953, a French newspaper published a letter claiming to that Zola’s death was perpetrated by a pro-nationalist stove-fitting contractor who had deliberately blocked the chimney whilst working on the roof of the house next door.

The following morning, they unblocked the chimney, leaving without a trace. It is not known if this story is true or not. Zola had made a great many nationalist enemies after his involvement in the Dreyfus affair, so it is entirely plausible.

What Zola left behind was a legacy as one of the greatest novelists of the late 19th century. His written works had an enormous impact on Western literature as he championed the lives of the poor and downtrodden.

He believed in the betterment of society through individual and collective action and his novels reflect this pursuit. Though many of his characters are ultimately tragic figures, they steadfastly stand by their ideals and are unwavering in their conviction. In this way, Zola wrote himself into his work and his legacy is one of immense bravery and belief in social justice.