1. Dejeuner sur l'Herbe (Manet, 1862-3)

Dejeuner sur l’Herbe (Lunch on the Grass) is the work that kick-started the impressionist movement.

Submitted by Edouard Manet to the Salon des Beaux Arts (the annual exhibition organised by the influential and conservative Academy des Beaux Arts), Lunch on the Grass was rejected by the jury.

The painting was instead displayed in a different exhibition held in 1863 called the Salon des Refuses (the “exhibition of the refused”), open to the 3,200 works that had been rejected by the Salon’s jury.

Critical reaction

The painting received a hostile reaction from both the public and reviewers. The public attended the Salon des Refuses in droves to mock and laugh at the work.

Interesting fact...

Reviewers said that Lunch on the Grass was so lacking in finesse that it could have been painted with a “floor mop”, that the figures reminded one reviewer of marionettes, and that the work was nothing more than a “young man’s practical joke”.

The problem was that the painting was not art as the French knew it. It did not depict Greek mythology, Roman history or a religious scene. And it was not produced using fine blended brush strokes that produced a near-photographic effect. Instead it used bold colours, broad un-blended brush strokes, and depicted a risqué modern scene.

The French would not come to appreciate such paintings for another two or three decades.

Clothed men, naked women?

As for the work, it has a striking nude female in the foreground chatting with two well-dressed young men. Another female bathes in the mid-ground. The four figures are depicted under a fairly coarsely painted canopy of leaves.

Interesting fact...

The eye is immediately drawn to the nude, but closer inspection raises a number of questions. Why are the men fully clothed when the woman is naked? Is she a prostitute? Why is the bathing female figure clothed? What is she doing (washing her feet, fishing ...)? Does the painting have a real problem with perspective?

Though interesting, such debates miss the real point. Manet was making a controversial statement with this work. He was challenging the orthodoxy and showcasing his new techniques. And it worked: the whole of Paris started to talk about him.

Where can I see it for myself?

Le Dejuner Sur l’Herbe is found in the permanent collection of the Musee D’Orsay in Paris. London’s Courtauld Gallery has a smaller earlier version of the work.

You might also enjoy our page on Manet's life story. Did you know that he fought a duel in February 1870?

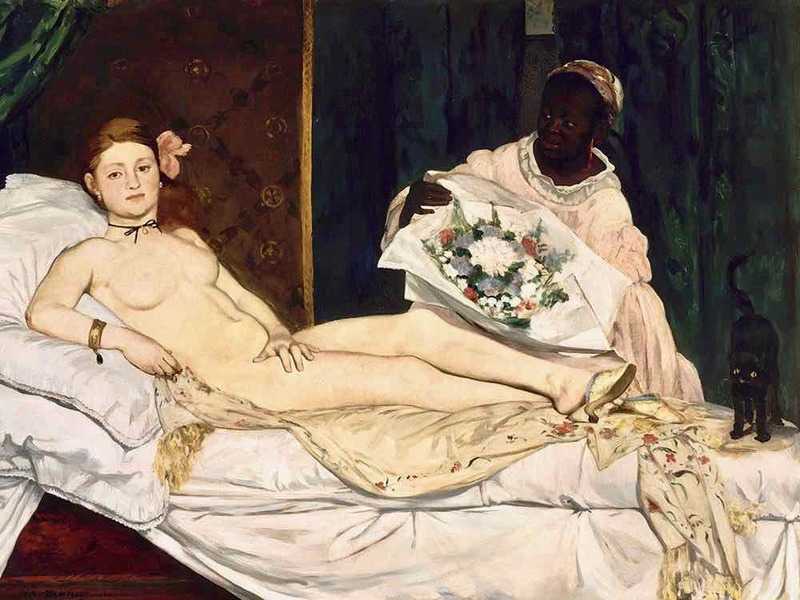

2. Olympia (Manet, 1863)

Though painted in 1863, Manet hid Olympia in his studio for 18 months before deciding to show it at the 1865 Salon. He knew that it would be controversial.

The painting

The painting depicts a Parisian prostitute lying naked on a bed, her left hand covering her modesty. Behind her stands a servant carrying a bouquet of flowers that have presumably been sent by a satisfied customer (not that Olympia seems remotely interested in them). And to the far right is a black cat with its tail raised.

Interesting fact...

There can be no doubt that the painting depicts a prostitute: Olympia was a name associated with the sex industry at the time. So were black cats. And Olympia’s appearance (orchid in hair, pearl earrings, black ribbon around her neck, bracelet and oriental shawl) is deliberately sensual.

The picture uses broad brush-strokes, and so could have been criticised by the establishment for this reason. But it was the courtesan’s unapologetic and brazen stare that caused uproar. The outrage was suffused with hypocrisy: in the mid-nineteenth century prostitution was rife in Paris (some studies suggest that almost half of the male population visited brothels on a regular basis).

The reaction

Manet was optimistic when Olympia was accepted by the Salon’s jury, writing “it won’t be too bad a year”. He couldn’t have been more wrong: a few weeks later he wrote to a friend to say that

“Insults are beating down on me like hail. I have never been through anything like it.”

That was no overstatement. One critic wrote that “Never has a painting excited so much laughter, mockery and catcalls as this Olympia”. Another said that “Nothing can convey the visitors’ initial astonishment, then their anger or fear”. A third that Manet’s motivation was to “attract attention at any price”.

Yet more critics wrote that Manet’s prostitute was a “female gorilla”, a lady of “perfect ugliness” and “a corpse … at an advanced state of decomposition.”

Manet travelled to Spain to escape the furore.

Where can I see it for myself?

Olympia was bought from Manet's widow, Suzanne, shortly after his death. It was paid for by a public subscription organised by Monet, which raised almost 20,000 francs, so that it could be hung in the Louvre (though it languished in the less prestigious Musee du Luxembourg until 1907).

These days Olympia is to be found in the Musee D’Orsay.

3. Impression Sunrise (Monet, 1871)

Impression Sunrise is the work that coined the word "Impressionism".

Disillusionment

By 1873, the group that would become known as the Impressionists had become thoroughly disillusioned with the Salon and had decided that they would host their own exhibition. Or most of them had: Manet refused to join the independent exhibition as he feared that it would further ostracise him from the French art establishment.

The group's first exhibition, held in 1874, included works by Monet, Cezanne, Renior, Degas and Pissarro and was hosted at the Rue de Capucines.

The group formed a company in which they each held shares and charged an entrance fee of 1 franc. Attendance was good (some 3,500 came), but Manet’s bad experiences of the Salon were repeated: the public came to jeer and the reviews were hostile.

More hostile reviews ...

One reviewer said that the exhibition was the work of a practical joker, who had amused himself by

“dipping his brushes into paint, smearing it onto yards of canvas, and signing it with different names”.

But the most famous and long-lasting review came from Louis Leroy, who wrote a spoof article about an art critic being shown around the exhibition by an art student. Of Impression, Sunrise, the critic remarks

“What freedom … what flexibility of style! Wallpaper in its early stages is much more finished than that.”

They, of course, didn’t get it: the Impressionists were trying something new; paintings that reflected what they felt about a scene, not paintings which were close to a photographic representation.

Leroy's article had an unintended effect. He used the word 'impression' as a term of insult; but the group gradually started to call themselves the "impressionists".

The work itself

Impression Sunrise is in fact a painting of the port at Le Havre, Monet’s home town, at sunrise. The eye is drawn to two small rowboats in the foreground and the red sun and its reflection in the water. Behind them are smokestacks coming from chimneys and the masts of clipper ships, giving structure to the work.

Where can I see it for myself?

Impression Sunrise is found in Paris' Marmottan Monet Museum, a small museum displaying more than 300 of Monet's works. It was stolen by five masked gunmen in 1985 and not recovered for five years (having been hidden in a small Corsican villa).

You might also enjoy our page on Monet's life story. Did you know that he was often penniless and once tried to commit suicide?

4. The Dance Class (Degas, 1870-1874)

Degas’ Dance Class series, painted at the rehearsal rooms of the Paris Opera in the early 1870s, are his classic impressionist works.

Degas

Edgar Degas, the son of a wealthy banker, was a complex individual. Degas’ father (unlike Manet's) did not rail against his son’s artistic ambitions. But Degas started out as a classical artist, copying the paintings of old masters in the Louvre and in Italy, Holland and Spain. He was not bitten by the impressionist bug until the early 1870s.

Degas exhibited at a number of the eight impressionist exhibitions held in and after 1874. Indeed, he played a key role in organising them. But his involvement was always controversial: he was demanding, cutting and didn’t like being called an impressionist.

Interesting fact...

Degas was difficult in other ways too. He would occasionally accept dinner invitations, but only if a long list of conditions were met: no cooking in butter; no flowers on the table; no perfume on female diners; no pets in the room; dinner to be served promptly at 7.30; and lights to be dimmed. He also, according to van Gogh, “... lives like a little notary who dislikes women”.

Degas refused to paint outside and indeed did not much like landscapes. It was this that made the opera house and its ballet practices ideal.

The Dance Class

Degas’ Dance Class series ticks all the impressionist boxes: they are modern scenes; they use bright colours; and they give the viewer the sensation of movement. They are also, as per Degas’ personality, devoid of any sentimentality.

Interesting fact...

But these are not paintings of the children of the wealthy elite. The dancers pictured are the offspring of the poor and the Parisian demimonde, seeking to earn a living. They practiced for long hours under the harsh tutelage of the famous and imperious dance master, Jules Perrot, who is often pictured in a standing pose resting on a large stick.

Degas’ main motive in painting ballet dancers was financial: they sold well. And, by the 1870s, Degas needed the money because his brother had run the family business into the ground.

Where can I see it for myself?

Versions of Degas’ Dance Class are found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and in Paris’ Musee D’Orsay.

You might also enjoy our page on Degas' life story. Did you know that Degas was an Anti-Semite?

5. Gare Saint-Lazare (Monet, 1877)

In 1877, Monet had a very good idea: he would paint fog.

But he didn’t want to wait around for the weather. He then had another very good idea: he would paint the steam and smoke of a railway station. But that too was a bit tricky: he would need to be allowed access to the platform, and would have to contend with trains coming and going.

The Station Master

Monet’s answer was a stroke of genius. As Renoir later explained:

“He [Monet] put on his best clothes, pulled his lace cuffs to rights, and, idly swinging his gold headed cane, handed the director of the western railways his card. The official froze, and ushered him in forthwith. The exalted personage asked his visitor to take a seat, and the latter introduced himself simply with the words ‘I am the painter Claude Monet’”.

The rest is history. Monet told the station master that he had been weighing up the competing virtues of the Gare du Nord and the Gare Saint-Lazare, and that he had come down in favour of the station master’s establishment.

For his part, the station master did not know much about art and so did not dare challenge Monet’s credentials. And, thinking that he had got an advantage over the Gare du Nord, he gave Monet everything he wanted: platforms were closed off; trains fired full of coal; departures delayed.

After days of painting, Monet left with half a dozen canvasses.

The paintings

They are tremendous successes: the viewer can almost feel the heat, noise and smell of the station. As one reviewer remarked, the paintings recreate the impression produced on travellers by the noise of the engines coming and going.

Even Albert Wolff, one of the most conservative commentators of the day, gave a back-handed compliment: the painting evoked the “disagreeable impression of several locomotives whistling all at once.”

Interesting fact...

The Saint-Lazare paintings had a more practical effect too. Paul Durand-Ruel, the impressionists’ most dependable gallery owner, bought the lot from Monet and advanced small sums to the rest of the group. He could see that they were powerful impressions of modern life. This was important: at this time, Monet was living from hand to mouth.

Where can I see it for myself?

Monet painted 12 pictures of Gare Saint-Lazare in all. They are found at, amonst other places, London's National Gallery and Musee D’Orsay in Paris.

6. Luncheon at the Boating Lake (Renoir, 1880-1)

Luncheon at the Boating Lake is a classic Renoir: it is contemporary, shows people enjoying themselves, is painted with fluid brushstrokes, and is finished in Renoir’s familiar rich and glossy style.

The painting

Renoir loved the boating lake just north of Chatou/Croissy. It was adjacent to the Hotel Fournaise, where Renoir had courted his wife Aline and where the two often returned in summer.

The painting is thoroughly impressionist: it depicts a modern scene, contemporary clothing and does not seek to impart any moral message. This is just about people having fun on a Sunday afternoon.

This was in keeping with Renoir's general philosophy of painting. As he said:

"a picture has to be pleasant, delightful and pretty -- yes, pretty. There are enough unpleasant things in the world without us producing more."

The details

Aline is pictured in the foreground with a griffon dog on her lap. She is talking to a group of people who include the impressionist painters Gustave Caillebotte and Mary Cassatt.

The painting is particularly impressive for rolling three genres into one: portrait, still life (see the fruit on the table) and landscape (see the lush foliage in the background).

Reaction

But whilst Renoir’s love life was in order, his career was still struggling. Like the other impressionists, he could not find regular purchasers of his work and went through a crisis in the summer of 1881 that led to his so-called Dry Period (he worried he was stagnating and wondered whether he should head in a new artistic direction). Indeed, he often paid for his food and lodgings at the Fournaise by donating paintings.

Interesting fact...

Luncheon at the Boating Lake was featured in the seventh impressionist exhibition, held in 1882. It even obtained back-handed compliments from a number of otherwise hostile critics. They included Armand Silvestre’s comment that it was one of the best pictures that “this insurrectionist art by Independent artists has produced” and Albert Woolf’s acidic observation that “If he had learned to draw, Renoir would have a very pretty picture”.

To learn more, check out our August Renoir biography page. Did you know that Renoir started his career by painting porcelain in a factory?

Where can I see it for myself?

Luncheon at the Boating Lake appears in the film Amelie and is the star attraction of Washington DC’s Phillips Collection.

7. Bar at the Folies-Bergere (Manet, 1882)

By 1882, Manet was dying of tertiary syphilis.

But he was still keen to paint and exhibit his works at the official Salon des Beaux Arts, where he had finally achieved success the previous year (being awarded a second class medal for a painting of the aristocrat Henri Rochefort). This was important: it meant that Manet was able to exhibit works without the consent of the hostile jury.

The Bar at the Folies Bergere was one of two works he submitted in 1882.

The painting

The painting is a classic Manet:

- it is principally a portrait, the type of work for which Manet is best known;

- it is a painting of one of the most exciting venues in Manet’s beloved Paris (the Folies Bergere often had circus acrobats performing, as can be seen from dangling feet at the top left of the picture); and

- the work is thoroughly modern (showcasing electric lighting, beer bottles from England and imported tangerines).

The painting, like many of Manet’s works, is enigmatic. The barmaid, Suzon, stares blankly at the viewer, seemingly lost in thought. In many ways she is dressed demurely, but she wears a black necklace that reminds the viewer of the ribbon work by Victorine in Olympic.

Interesting fact...

Suzon seems to be in intense discussion with a top-hatted gentleman. But are they talking about beverages or something far more serious? Is he a patron, a lover or Suzon’s disapproving father?

Reflection

Most important, however, is the curious use of reflection. The bar clearly has a large mirror behind it. But Manet intentionally plays with the reflection to give us a good view of Suzon’s back and the man she is talking to. The result baffled contemporaries and puzzles to this day.

Manet was too ill to paint the work at the Folies Bergere: Suzon had to come to his studio to pose behind a specially constructed bar.

Where can I see it for myself?

The Folies Bergere, Manet’s last major work, is found in London’s Courtauld Gallery.

8. The Card Players (Cezanne, 1890)

Cézanne is most famous for his series of five Card Players. One of the series set a world record price: it sold for $259 million in 2011.

Cezanne

Paul Cézanne was a complex fellow. Born in Aix en Provence in southern France, he struggled for years to escape his domineering father. He was ill-tempered and much of his early work was quite disturbing (it even includes paintings of murders).

But with Pissarro’s encouragement and support he was brought into the impressionist fold and exhibited in two of their eight independent exhibitions (though he attracted appalling reviews!).

For instance, one critic wrote after seeing A Modern Olympia that Cezanne was a

“sort of madman, painting in a state of delirium tremens”.

By the 1890s, Cezanne had become estranged from his wife and best friend, Emile Zola, and was almost entirely devoted to his art.

The paintings

Cezanne's series of five Card Players all depict local Provençal farmhands focussing intently on their games of cards. Two pictures show three card players; the remaining paintings only two.

The works are striking for a number of reasons:

- The players sit inertly and seem totally detached from each other.

- The proportions of many of the players seem odd: check out the small heads, long arms and large bodies.

- Pipes and hats feature heavily (Cezanne’s father had a hat business before he became a banker).

- The colour blue—a Cézanne favourite—is prominent in all but one of the paintings.

Cézanne completed many studies before painting the five works, with the usual assumption being that the larger three player pictures came first.

To learn more, check out our Paul Cezanne biography page. Did you know that Cezanne hid the fact that he had a son from his father for nine years?

Where can I see it for myself?

Four of the Card Players are on public display at the Barnes Foundation Philadelphia and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (the three player versions) and at the Musee D’Orsay in Paris and Courtauld Gallery in London (two player versions).

Most critics regard the D’Orsay’s version as the best. The final version is in a private collection, having been bought by the Qatar Royal Family for a world record $259 million in 2011.

9. Boulevard Montmartre (Pissarro, 1897)

Pissarro may not be the most famous impressionist. But he was the glue that held the impressionist movement together.

Pissarro

Born in the Danish West Indies (now the US Virgin Islands) in 1830, Camille Pissarro was an essential member of the impressionist group.

For example, he was instrumental in arranging the first independent impressionist exhibition in 1874, and he was the only impressionist to exhibit in all eight impressionist exhibitions.

Pissarro's friendly and relaxed approach to life allowed him to mediate between difficult personalities like Degas and Cezanne. In fact, Cezanne described Pissarro as:

"a good man to consult and a little like the good Lord".

The paintings

Between February and April 1897 Pissarro took rooms at the Hotel de Russie in Paris and produced a series of 14 paintings of Boulevard Montmartre at different times of day and at different points during the year.

Painted from exactly the same position, the collection includes the Boulevard:

- in winter (when the trees have no leaves) and in spring (when they are in blossom),

- in sun (when the street is bustling) and in rain (when it is fairly deserted), and

- in fog, mist and at sunset.

Three members of the series even depict the Boulevard during the Mardi Gras celebrations.

Seven of the paintings are now found in the world's top museums, including London's National Gallery and the Met in New York, with the other seven in private collections.

Boulevard Montmartre: Spring sold for a record £19.1 million in 2014, the record price for a Pissarro.

Boulevard Montmartre at Night

Only one of the paintings shows the road at night. Using fairly coarse brush strokes and bold colours, this stunning work depicts the bright lights of shops, theatres, gas lights and taxis on a wet Parisian evening.

Pissarro even catches the reflection of the bright lights against the dark sky: an early example of light pollution!

Where can I see them for myself?

Versions of Boulevard Montmartre can be found in London's National Gallery, the Met in New York, the Hermitage in St Petersburg, and in other galleries in the US, Switzerland and Australia.

To learn more, check out our Camille Pissarro biography and Boulevard Montmartre series pages. Did you know that van Gogh called Pissarro the "father to us all"?

10. Water Lilies (Monet, 1895-1926)

Monet, the most famous impressionist today, is best known for his water lilies.

In total, there are over 250 paintings in the series, produced over the last 30 years of Monet's life.

Giverny

Monet moved to Giverny, a small town outside Paris, in 1883 (the year of Manet’s death). He rented a large farmhouse to start with, purchasing it about a decade later as his work increased in popularity and price.

Interesting fact...

It took Monet a little while to win over the suspicious locals. Some of them charged him to walk across their fields, whilst others even dismantled haystacks and threatened to lop poplars as Monet was trying to paint them.

But this didn't stop Monet from turning Giverny into his personal Eden. He purchased a field below the house in the early 1890s and set about turning it into a water garden. He later engaged a gardener to tend to the pools and lilies on a full-time basis.

Giverny was where Monet continued to paint with remarkable industry until his death. He rose early, had a hearty breakfast and went to work. Lunch was served at 11.30 so that Monet would not miss the afternoon sunlight. Tea was taken in the garden and Monet retired to bed early so that he could repeat the process!

The Water Lilies

For thirty years from the mid-1890s, Monet principally painted water lilies. This was easily his most comprehensive series of paintings (he also painted many versions of Haystacks, Poplars, Rouen Cathedral and the Houses of Parliament).

The works are impressive on so many levels. Nobody has ever used colour, light and reflection so skilfully.

Then there is the huge range of pictures: paintings of pond scenes, the Japanese bridge that Monet had installed in 1906, and extreme close ups of a handful of lilies. Some of the canvasses are enormous, especially those now housed in the Musee de l'Orangerie in Paris.

Finally, there is Monet’s industry: he painted virtually every day, often with a dozen canvasses on the go at once.

Interesting fact...

Monet continued to paint Water Lilies notwithstanding that his vision was from about 1908 impaired by cataracts (he eventually agreed to have them surgically removed). Monet used much more red and orange during his cataract years.

Monet was the longest-lived of the impressionists: he outlived Manet by over four decades and Renoir by seven years. He was painting water lilies until his death in December 1926.

Where can I see them for myself?

Versions of Water Lilies can be seen around the world. London's National Gallery and Paris' Musee D'Orsay hold versions. So too does New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, Washington's National Gallery and Tokyo's National Gallery of Western Art. Paris' Musee de l'Orangerie was specially built to Monet's exacting specifications to hold his bequest of 12 enormous waterlilies.

11. Bonus entries: Vincent van Gogh

Van Gogh is one of the world's most famous artists on account of his striking paintings, self-mutilation and premature death by his own hand.

Van Gogh's life

Born in 1853 to well-off but conservative parents, Vincent van Gogh had a troubled life.

Serious and introspective, he worked as an art dealer and missionary before taking up painting full time in 1881. Van Gogh's early works are mostly still lifes and paintings of labourers in earthy tones (such as the Potato Eaters).

They do not suggest the splashes of colour that were to follow van Gogh's move to Paris and introduction to impressionists such as Degas and Gauguin.

Van Gogh's most famous works were painted between 1887 and his death in July 1890. Over this period van Gogh suffered serious mental health issues.

He checked himself into a sanatorium after he severed his left ear in December 1888, following an argument with Gaugin, and delivered the bloody mess to a brothel that he frequented. And he shot himself in chest with a revolver in July 1890, dying of his injuries two days later.

To learn more, check out our page on van Gogh's life story. Did you know that van Gogh trained to be a priest?

van Gogh's work

van Gogh played no part in the impressionist exhibitions of the 1870s and 1880s and is usually categorised as a post-impressionist. His works, however, have a definite impressionist flavour: painted outdoors with wide, coarse brushstrokes and bright colours.

Indeed, van Gogh developed his more adventurous technique partly as a result of time he spent in Paris with some of the impressionists in the mid-1880s.

Van Gogh's most famous and striking works include Sunflowers (of which he produced several versions in and after 1887), Irises (1889) and Starry Night (1889, the subject of Don McLean's eponymous song).

Where can I see them for myself?

The best place in the world to see van Gogh's work is the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. But his works are found in the world's best galleries. London's National Gallery has a version of Sunflowers and the excellent Wheatfields with Cypress Trees. The Museum of Modern Art in New York has one version of Starry Night and Paris' Musee D'Orsay has another.