1. Pissarro's early years

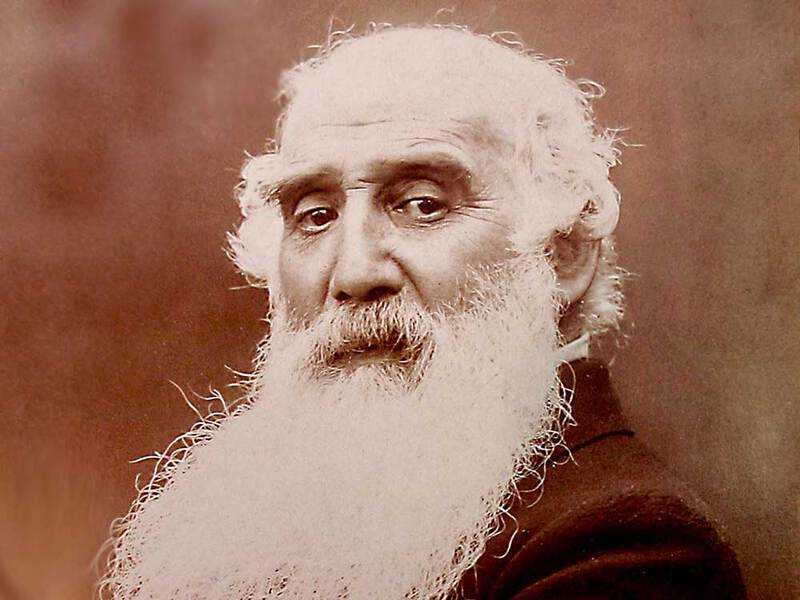

Jacob Abraham Camille Pissarro was born on the Island of St Thomas in the Danish West Indies on 10 July 1830.

His father ran the hardware store in St Thomas' capital, Charlotte Amalie, and his mother was a local woman previously married to Pissarro's deceased uncle.

Pissarro spent his formative years on St Thomas, being sent to a boarding school outside Paris at the age of 12 in 1842. He returned to St Thomas in 1847, whereupon he worked in his father's business as a cargo clerk.

Pissarro loved drawing and painting and applied himself to his art outside work. He was persuaded by Danish artist Fritz Melbye to become a full-time artist in 1851, and followed Melbye to Venezuela where the two men shared a studio and Melbye acted as Pissarro's mentor.

Pissarro moves to Paris

Pissarro decided to move to Paris and arrived in 1855, in time for the Universal Exhibition.

It included a substantial art section, dominated by the twin-titans of French art of the time: the romantic painter Delacroix and the traditionalist Ingres. Also represented was the realist school of art, in particular the works of its standard-bearer Corot.

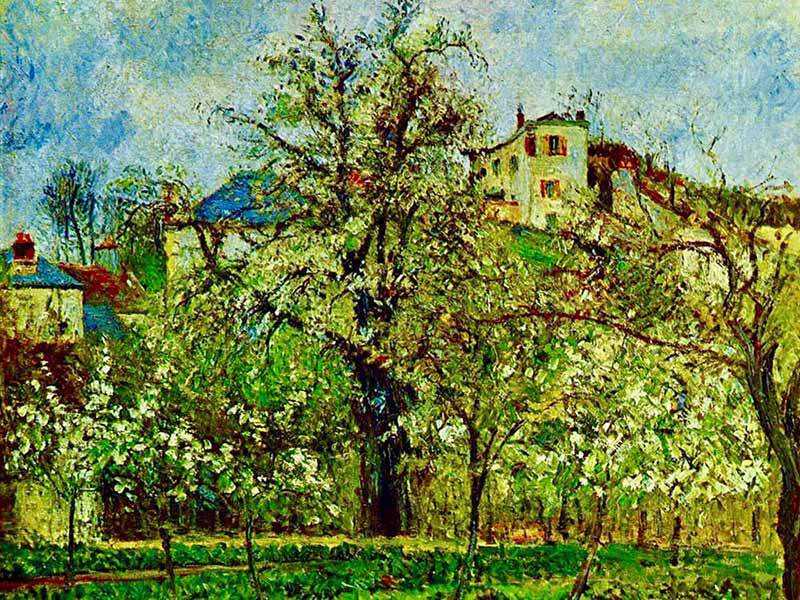

Pissarro was initially attracted to the realist school, and received informal mentoring from Corot. Painting en plain air (outside), he produced mainly rural scenes and was accepted by the Salon for the first time in 1859. He was to have he work accepted in the Salons of 1864-6 and 1868-70, initially describing himself as a "Pupil of Corot".

Typical of Pissarro's output over this period is the pictured The Marne at Chennevieres (1864).

Pissarro meets Monet and Cezanne

Pissarro met Claude Monet and Paul Cezanne while attending the Suisse Painting Academy in 1859.

The three men were all dissatisfied with the traditional French art establishment, which encouraged religious and mythological works over almost all else and frowned upon painting en plein air (outdoors) and the use of loose brush-strokes.

Pissarro formed a particularly close bond with Cezanne over this period, being a source of comfort to Cezanne when his works were mocked by fellow students and art critics.

2. The impressionist exhibitions

Tragically, many of Pissarro’s earlier works were destroyed as a result of the Franco-Prussian war, most likely by Prussian soldiers during the 1870/71 Prussian War.

From over 1,500 works, only 40 remained. Pissarro himself fled to London for his own safety where he met up with Monet.

Pissarro also used his time in exile to paint a number of works of suburban London, includingThe Avenue at SydenhamandLordship Lane Station, Dulwich.

On his return to France, Pissarro began musing about creating an alternative to the Salon de Paris. The restrictive stylistic rules and biased judging system enforced by the Salon did not give him and his fellow Impressionists proper recognition for their new stylistic achievements. The idea was to create a society that was distinct from the French Academy where they could set their own rules and make a name for themselves.

The Anonymous Society

After discussions within the group, they agreed to establish the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors and Engravers. With the help of Monet, Pissarro set about organising the first Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1874. It was held at 35 Boulevard des Capucines, the studio of Nadar the photographer, or Gaspard-Félix Tournachon. In total, 30 artists displayed 165 pieces of work at the exhibition.

The First Exhibition

This first, subversive event was where the Impressionists got their name. Thanks to one critic’s derision of Monet’s work ‘Impression, Sunrise’, dismissing it as merely an ‘impression’ or an unfinished piece, the 'impressionist' label was born. The group adopted the term with pride and by 1887 they were calling themselves 'the impressionists' and encouraging others to do the same. Until this point, they had largely been known as the ‘independents’ or the ‘intransigents’.

Pissarro's contribution to the first exhibition was to exhibit five landscape paintings.

Later Exhibitions

Following the first 1874 exhibition, seven more exhibitions were held in the years between 1876 and 1886. The Salon continued to reject the impressionists’ artwork so the exhibitions became a regular event, despite mainly negative reviews from critics and a cool reception from most of the public. Ultimately, however, they were critical in introducing impressionist works to a larger audience.

Pissarro was the only artist to show his work in every single exhibition and he was instrumental in bringing new blood to the exhibition as other artists left the group. Berthe Morisot, the leading female impressionist, was the next most loyal, showing her work in seven exhibitions.

He happily accepted Degas’ influence in the 1881 exhibition, whilst other artists resented what they perceived as his takeover. Through the many upheavals the group faced, Pissarro remained steadfastly loyal to the movement and refused to return to the Salon.

3. Pissarro and Pointillism

To keep his work new and interesting, Pissarro began experimenting with neo-impressionist techniques.

He dabbled in pointillism for a time but it did not hold his attention. Within a few years Pissarro had reverted to his previous, looser style.

Father and Son

Pissarro ventured to experiment with the techniques thanks to his son, Lucien, who was enthusiastic about the work of Georges Seurat. In 1886, both father and son submitted Neo-Impressionist paintings to the exhibition, though Pissarro’s landscape scene used softer brushstrokes.

Pissarro’s pointillism contrasted with his previous works in part due to the extensive planning required. He preferred to paint quickly and easily but pointillism involved rigorous scientific method and detailed studies before the final painting could be embarked upon. The mechanistic approach of building up a picture with small dots also made it hard for him to portray the movement he wanted.

As a result, Pissarro's productivity during the years experimenting with pointillism was much lower than usual. Nonetheless, he maintained his habit of depicting peasant life, contrasting with the landscapes and gentile scenes favoured by many of his contemporaries. This technique allowed him to capture the vivid colours of the peasants’ clothing, seen most clearly in his work ‘Peasant Women Planting Poles into the Ground’ from 1891.

The final exhibition

In the final Impressionist exhibition in 1886, Pissarro, Seurat and Signat’s work was displayed in a separate room. This set them apart from the impressionist art movement and demonstrated a clear break for Pissarro from his previous styles.

His piece, ‘La Maison de la Sourde et Le Clocher d’Eragny’ (House of the Deaf Woman at Eragny, pictured), 1886, used the view from his home as its subject, looking over his neighbour’s house and the steeple of the parish church.

Similarly, the soft tones, built up through precise dotted brushstrokes, allowed him to mimic the bright sunlight of the scene. Due to the larger scale of the piece compared to many other pointillist paintings, it is now treasured as a key example of neo-impressionism today.

Influence on later work

Despite abandoning the technique fairly quickly, there is evidence that Pissarro’s work retained some aspects of pointillism for the remainder of his life.

In particular, the way he used colour harmonies was changed by pointillist theory. He continued to play with juxtaposing complementary colours alongside one another, using small, quick brushstrokes to build up his paintings and thereby blending the Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist styles. Moreover, he learnt how to make monotone colours and greys into rich, bright tones.

This helped to create a vivid colour palette for many of his works, bringing his ordinary rural scenes to life.

4. Pissarro's Later Life

In spite of his influence in impressionism, Pissarro had money worries for much of his life.

In the early 1880s, the French economy fell into deep depression, due in part to an international economic crisis, beginning in 1873, and reparations owed to the Prussians after France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian war. In 1882, the Paris stock market crashed. No one was buying art at this time.

France’s economic woes further hindered Pissarro’s efforts to sell his work and money became a serious concern for him. In spite of these dire circumstances, he resolved to “calmly tread the path I have taken, and try to do my best”, as he wrote in a letter to his son. He continued with his experiments.

Mature Period

Following pointillism, Pissarro moved into a new era of painting that was more mature than his earlier works. Thankfully, these were well received by many dealers and collectors who recognised the evolution in his art. In the early 1890s, Pissarro was finally able to achieve some financial security.

In his later paintings, Pissarro concentrated his efforts on creating magnificent cityscapes, retuning to Impressionism but focussing on urban scenes this time. Whilst many of his contemporaries were beginning to reject the city as a subject, Pissarro wholeheartedly embraced it. Paintings of Paris and the port city of Le Havre transformed his art into sprawling masses of buildings and people, a churning world in endless motion, painted with his characteristically deft touch.

Due to chronic eye problems, Pissarro was forced to paint inside. ‘Le Boulevard Montmartre, fin de journée’ is one example of his Parisian scenes, showing the city filled with vibrant life and excitement.

Boulevard Montmartre

The Boulevard Montmarte series is one composition that he chose to paint over and over from the same position of his hotel room. It is one of our top 10 impressionist paintings.

He painted this series with different views and street scenes, experimenting with the weather transitions, the changing seasons and the time of day to show the variety of city life. However, unlike other Impressionist series, those by Monet in particular, Pissarro did not intend for his paintings to be hung together.

The street scenes he depicted were influenced by Napoleon III’s radical redesign of the city, newly built on top of the medieval houses that were destroyed to make way for his vision. Pissarro praised the modernity of the new cityscape and enjoyed the uninterrupted views they provided him for his work.

Critics have suggested that Pissarro’s series were not painted for any particular purpose or to garner excessive praise but simply because he liked painting them. He found the change to urban landscapes diverting but did not struggle with the meaning behind his painting style or how it would be defined by others. He was, as ever, unafraid of going against convention.

5. Pissarro's legacy

Pissarro was unlike any of his contemporaries.

Not simply because he experimented with pointillism or because he was the only Jewish artist among the impressionists, but mostly because he was largely forgotten after his death.

Obscurity and recognition

For much of the 20th century, Pissarro's work was left in the shadows, only beginning to gain recognition in the 1980s. Unlike many of the Impressionists, he did not become a household name until much later in history. It is not known if this was a result of the anti-Semitism that swept through France and Europe in the later 19th and early 20th centuries or purely down to changing tastes in the art world.

Regardless of the reason, Pissarro is now accepted as having had a monumental impact on impressionism. His Boulevard Montmartre series in particular is seen as amongst the most masterly impressionist works. Unlike many other impressionists, Pissarro also favoured rural subjects for the majority of his career.

Impact on the other impressionists

Pissarro's impact on other Impressionist artists is clear from their accounts of him. Van Gogh called him “father to us all” and Cezanne stated that

“he was one of my masters.”

His effect on Cezanne’s stylistic development in particular has been credited with pushing him to become the father of modernism in the 20th century. The outpouring of admiration and emotion towards Pissarro from some of the best known figures of the Impressionist movement is indicative of his influence on this era of French art.

Four of Pissarro’s children went on to become painters, as well as many generations of his family after them. He paved the way for other artists to follow but did not achieve the same level of fame. Even today, he is all too often forgotten for his important role, his name omitted from the many discussions of Impressionism in the art world and beyond.