1. Ingres' early life

Born in August 1780, Ingres was the eldest of seven children. His early life was shaped significantly by his relationship with his father, Jean-Marie-Joseph Ingres. Joseph and his wife Anne Moulet, Ingres’ mother, lived apart for long periods of time.

Surviving letters from Anne suggest that his father was an abusive partner and she suffered significantly as a result. Due to the strained relationship of his parents, Ingres grew up with very little contact with his surviving sisters, Augustine and Anne-Marie. He had no acquaintance with his twin brothers Pierre-Victor and Thomas-Alexis.

Art tuition

Joseph was the first person to teach Ingres about art. Ingres was a modest painter who lacked any particular specialism. He tried his hand as a sculptor, stonemason and musician as well.

Joseph had a strong belief in his abilities and sought to pass his knowledge onto his son. After his early schooling was disrupted by the revolution in France in 1791, Ingres began studying at the academy of fine arts in Toulouse, known as Academie Royale de Peinture, Sculpture et Architecture. His father moved with him to supervise his education, completely neglecting his wife and younger children.

It was here that Ingres learnt to play the violin and he was a key member of the Orchestre du Capitole de Toulouse for three years. Shortly afterwards, the talented young man began studying painting under Jacques Louis David in Paris in 1797. Described as one of the finest students in his class, Ingres was accepted into the École des Beaux-Arts within two years.

Early works

A painting of his father, dated to 1804 and titled ‘Jean-Marie-Joseph Ingres’ is gentle and flattering, suggesting the debt he felt he owed to him. Joseph encouraged Ingres to follow his artistic talent and this is reflected in Ingres’ portrayal of his father. This portrait contrasts with the sterner depictions that Ingres went on to paint for paying clients.

Ingres’ most notable painting from this time is ‘The Ambassadors of Agamemnon in the tent of Achilles’ also known as ‘The Envoys of Agamemnon’, painted in 1801. This neo-classical artwork won him the Prix de Rome the same year, granting him a scholarship to study in Rome at the Académie de France.

Students were charged with painting an event from the Trojan War as written in Homer’s Iliad. Instead of representing action, Ingres chose a more reflective subject, depicting the moment in which Achilles refuses to return to the Trojan War. This composition showed his early sensitivity and originality.

Ingres the portraitist

Thanks to Napoleon’s war-mongering politics at the time, Ingres was forced to renounce his scholarship and stay in Paris due to a lack of funding. Instead, he began working as a portrait artist, a career that offered young artists a considerable income. He was greatly inspired by Raphael and the engravings of the English artist John Flaxman.

At the age of 26, Ingres became engaged to a fellow painter and musician, Marie-Anne-Julie Forestier, who may also have been a pupil of David. Ingres’ drawing from 1806 of Julie and her family features several symbolic details, such as a dog to represent fidelity. They shared a love of music as well as art.

Love life

Unfortunately, the couple’s romance did not survive their separation when Ingres left for Rome in the autumn of 1806. Instead, Ingres married Madeleine Chapelle, a Parisian milliner who moved to Rome to live with him. Julie wrote a novel about her ill-fated romance with Ingres and continued to paint, never marrying. Some of her artworks were shown in the Salons of 1804 and 1819.

Whilst in Rome, Ingres’ life took a great number of twists and turns. He gained a reputation as an accomplished portraitist, completing paintings of prominent figures like Queen Caroline Murat in Naples and commissions from the French governor of Rome. Whilst these were privileged opportunities, Ingres was enormously affected by the political swings happening in Europe.

With the fall of Napoleon’s dynasty and the Murat regime, Ingres found himself trapped in Rome with no funds or patrons. He was forced to become a portraitist for English tourists, drawing miniatures in pencil for minimal reward. This pushed the artist’s pride almost to breaking point. It was only in October 1824 that Ingres and his wife were finally able to return to Paris.

2. Ingres' Neoclassicism

Despite his classical background and success in the École des Beaux-Arts, Ingres disliked the influence of the Salon on French art.

Ingres and the Salon

He saw it as a disrupting force that pushed artists to consider monetary gain and commercial success over the pursuit of originality. Ingres strongly believed that the Salon was smothering the beauty in art in favour of achieving recognition and glory.

In doing so, he aligned himself with the more revolutionary artists among his colleagues. These artists paved the way for the Impressionists to establish their own exhibitions, firmly breaking with the conventions of the Salon.

Nevertheless, Ingres continued to seek professional praise and recognition, choosing to pursue history painting. History painting was a highly respected genre at this time. Ingres’ paintings were Neoclassical in every way but he still tried to innovate in some respects. He deliberately chose more emotional and psychological subjects than many of his peers, hinting at the influence of Romanticism on his work.

Ingres and Delacroix

One of the most notable features of Ingres’ professional life was his rivalry with Delacroix. Much like Constable and Turner, Ingres and Delacroix were the subject of much gossip thanks to their open contempt towards one another.

They grappled for favour at the Salon, each dismissing the other’s artistic style, one as a Romantic painter with a love of colour, the other as a restrained, refined academic painter.

The two rivals have often been placed at opposite ends of a spectrum to highlight their divide: Delacroix as a flamboyant and sensual artist compared to Ingres who focussed on clean lines and strict rules. In the Universal Exhibition of 1855 in Paris, the two artists had to be physically divided into separate rooms to avoid conflict.

Such a contrast between the artists has arguably been heavily exaggerated for the sake of drama. Whilst their painting style is certainly different in many ways, Ingres’ work does not lack intensity. Look closer at his detailed, precise work and there is an underlying passion. Even Delacroix admitted in his journal that Ingres’ work had “many fine qualities”. He was one of the few supporters of Ingres’ 1811 work depicting Jupiter and Thetis, which was heavily criticised by the Paris establishment.

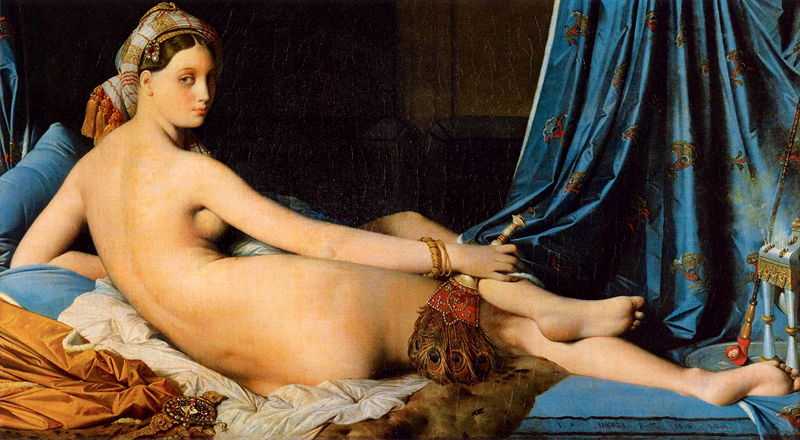

Ingres’ nudes

In fact, Ingres’ art incorporated erotic styles from the Near East, combining them with western styles and the Romantic’s love of mythology.

In doing so, he was able to paint female nudes whilst remaining removed from outrage, focussing on exoticised figures from ‘the Orient’. It was only when the Impressionists began painting nude women from France that people became outraged.

In his nudes, Ingres took inspiration from Botticelli and Italian Renaissance artists, whilst experimenting with his own colour palette. He used pure colours, described by Henri Matisseas

“outlining them without distorting them.”

With static lines he portrayed the female form in all the curving, bountiful beauty of the classical period. In this way, he also manipulated the bodies in his works, distorting them beyond natural limits to create a highly stylised final product. This is perhaps best seen in the elongated, disproportioned form of ‘La Grande Odalisque’ from 1814.

Ingres and the critics

One critic from 1832 described Ingres as “perhaps more of a sculptor than a painter; he occupies himself exclusively with line and form” stating that he “belongs in many respects to the heroic age of the Greeks”. As a result, Ingres can be understood as far more experimental than he has become known for, bridging the space between neoclassicism and romanticism.

Regardless of contemporary criticism, Ingres’ Dionysian works would go on to shape the radically candid nudes of the Impressionists, including Renoir, Mary Cassatt and Gustave Caillebotte. ’The Valpinçon Bather’ (1808) would eventually become Renoir’s ‘Nude Seated on a Sofa’ (1876) and Degas’ ‘Woman Combing Her Hair’ (1888-1890), both of which echo the soft light and candid pose of Ingres’ work.

3. Ingres and the Impressionists

The influence of Ingres on the Impressionists was often passed through their early painting masters. Many French academic and Neoclassical artists revered Ingres’ style and sought to emulate him, teaching this study to their pupils.

Perhaps the best example of this influence is Charles Gleyre, who taught Claude Monet, Frederic Bazille, Alfred Sisley, and Auguste Renoir.

Scorn?

However, the Impressionist movement was also a reaction against this formal training, instead seeking to represent everyday life in all its complexity, rather than emulate the stiff portraits of Ingres and his peers. As a result, Ingres was scorned by many young Impressionists.

The exception was Degas who was first introduced to the painter by Louis Lamonthe in 1854, whilst he was studying under Lamonthe. Degas’ father, an amateur artist himself, introduced the young painter to the Valpinçon family and it was likely through this prominent lineage of art collectors that Degas met Ingres. Other scholars have inferred that Lamonthe himself made the initial introduction.

Ingres and Renoir

Ingres was known as a stern painting master with strong ideas about how an artist should behave and the courage needed to succeed. It was perhaps this philosophy that led Renoir to gravitate towards Ingres during the 1880s as he struggled to find his own form of artistic expression.

From 1883 to 1884, Renoir attempted to break from Impressionist styles and undertook a new form of painting. Scholars have now termed this period as the ‘Ingres period’ thanks to the drier style he adopted in his artworks, emphasising form and line. Nonetheless, he continued to use the bright colour palette that had been championed by the Impressionist movement.

Renoir’s The Umbrellas

Renoir’s artistic shift and the influence of Ingres can be summarised in a single painting, ‘The Umbrellas’. First started in 1881 and eventually finished in 1885, this work shows the direct development of the artist’s stylistic tastes. It is a fascinating testament to his transformation, moving from the softer brushstrokes of the Impressionists to the harsher, linear styles of Ingres as the eye travels from right to left across the canvas.

The girl in the foreground has feathered ginger hair and blushing blues in her coat whilst the woman on the left, with her face angled directly towards the viewer, is far more definitive. Her face and black dress are solid and clean, lacking any of the dappling of his earlier style.

Ingres and Braquemond

Ingres similarly served as the painting master to the young Impressionist Marie Bracquemond from 1859. From Ingres, Bracquemond learnt how to paint in the academic style, as seen in many of her artworks which fuse Impressionist and academic influences.

Her time with Ingres was clouded by his biased approach to female painters who he believed lacked the perseverance and strength of character needed to be successful. He restricted them to painting still lifes and portraits, offering only his male pupils the chance to attempt more ambitious subjects.

4. Ingres and Degas

Despite Ingres’ influence on Bracquemond and Renoir, it was Degas who arguably had the strongest relationship with Ingres.

During their first introduction, Degas became more fascinated with the artist than ever before. This meeting was highly influential for the young artist and he held Ingres’ advice in his head throughout his career.

He is reported to have said, “Draw lines […] Lots of lines, whether from memory or from life”. These simple words evidently stayed with Degas and can be seen in practice in paintings such as ‘The Bellelli Family’ from 1858-1857, which echoes the clean, academic style of the great Ingres himself.

However, as their relationship progressed, Degas’ work became less and less allied to Ingres. He favoured freedom and looseness over the stricter lines of his idol, though he continued to claim that Ingres inspired his work.

The 1885 print ‘The Apotheosis of Degas’ can be seen as a direct parody of Ingres’ ‘The Apotheosis of Homer’ from 1827. The photograph was taken by Walter Barnes in the summer of 1885 and Degas sent cheap prints of the image to all his friends as a joke. Even whilst he criticised Ingres, however, this reproduction also showed Degas’ dedication to the aesthetic legacy of the master.

During the late 1800s, Degas collected a large number of Ingres’ works and continued to add to it for many years. His undying devotion to Ingres is best illustrated by his visits to a retrospective exhibition of the artist’s works in Paris in 1911.

By this time, Degas’ condition had deteriorated so dramatically that he had completely lost his eyesight. In spite of this, he went to the museum every day. His blindness meant he could no longer see the paintings he once loved but he would touch the canvases instead, feeling the lines and otherworldly forms that had inspired him through his career.

5. Ingres’ legacy

The legacy of Ingres is an intriguing one. There can be no doubt that globally he was not privileged with the same fame of his younger rival, Delacroix.

Outside of France, very few members of the public know of his work and he has often been misunderstood as being a rigid artist who depicted conventional portraits and artworks rooted firmly in the classical tradition.

However, there is an underlying sensuality to much of Ingres’ work that cannot be ignored. Ingres was adept at manipulating the figures he depicted, abstracting them in order to emphasise the impossible harmoniousness of the human body.

Art historians have pointed to the influence of Ingres in Matisse’s ‘Joy of Life’ painting from 1905 with the clean lines of the nude female figures echoing Ingres’ Neoclassical nudes. One of the best parallels is Ingres’ ‘Turkish Bath’ painting, produced between 1852 and 1859 and modified again in 1862. Similarly, this work can be seen echoed in Picasso’s later works from the 1920s depicting abstracted female nudes.

The post-impressionists further adopted a number of Ingres’ ideals, particularly his attention to architectural design and his clear, clean compositions. Cezanne was among the later admirers of Ingres. Whilst he was heavily rejected by many young artists, Ingres was also a key source of inspiration for some.