1. Matisse’s early years

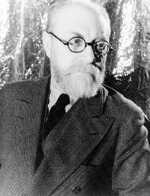

Matisse was born on New Year’s Eve in 1869.

His family lived in northern France and his parents were fairly middle-class. Emile-Hippolyte-Henri Matisse and Anna Heloise Gerard worked in the grain business and his mother was also an amateur painter. She was the first to advise her son not to bother with the “rules” of art and instead to follow his own emotional expression.

The student Matisse

Matisse’s earliest training was not in art but in law.

He moved to Paris to study law at the age of 19 before returning to his home of Saint-Quentinto work as a law clerk. Though it seems unbelievable now, this highly expressive artist held down a tedious office job for several months until he contracted appendicitis.

As a result of his illness, he was forced to spend many weeks at home recovering, during which time his mother bought him his first range of art supplies. This was the push Matisse needed and he began nurturing a private love of painting.

In 1891, fully recovered from his illness, he moved once again to Paris to study. This time, he chose to follow his new-found passion for art. He was initially rejected from the École des Beaux Arts and instead joined the studio of Gustave Moreau.

Gustave Moreau

Moreau was a symbolist painter and it is this early tutelage that has been credited with much of Matisse’s early experiments with colour.

Moreau taught his students that “Colors must be thought, dreamed, imagined.” Matisse followed this doctrine throughout his career, using colour as the imaginative force in all his works. He would later say of Moreau that, “He did not set us on the right roads, but off the roads. He disturbed our complacency.”

Matisse’s family

After persevering, Matisse was finally accepted to the École des Beaux Arts in 1895. Around this time, his lover Caroline Joblaud also gave birth to a daughter, Marguerite.

Matisse would go on to have two further children with his later wife Amelie Parayre, who he married in 1898. His family placed a significant financial burden on the artist, but he continued to firmly pursue a career in painting and amassed a significant collection of Post-Impressionist artworks.

The teenage Marguerite acted as a sitter in many of her father’s works. In later life, she would go on to become a leader of the French Resistance during World War II. She narrowly escaped death in a concentration camp when an Allied bombing raid disrupted the cargo train she was being transported in and she was able to flee to freedom.

2. Matisse and the Impressionists

During Matisse’s early art education, he was interested by the loose brushwork of the impressionists.

His first painting experiments were fairly conservative. It was only when the young artist was introduced to the work of Post-Impressionist Vincent Van Gogh in 1897 that his work changed dramatically.

Experiments with colour

Like the Impressionists, Matisse believed in the expressiveness of colour and followed that it need not be a direct representation of the colours in nature. Following the example of Impressionist artists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, Matisse experimented with using colour to denote feeling in his work.

In doing so, he moved further and further away from the need for realistic representation, experimenting instead with creating a sense of balance and pleasure in his paintings.

Where Matisse went beyond the Impressionists was in his goal of separating colour from representation entirely, allowing colour to be present in his artworks as a stand-alone element of the composition.

He longed for an even brighter palette, completely removed from the constraints of nature. He began using blocks of colour that had nothing to do with descriptive duties.

Japanese art

Matisse further drew inspiration from the influx of Japanese art into Europe, as seen in the works of Impressionists like Mary Cassatt and Gustave Caillebotte.

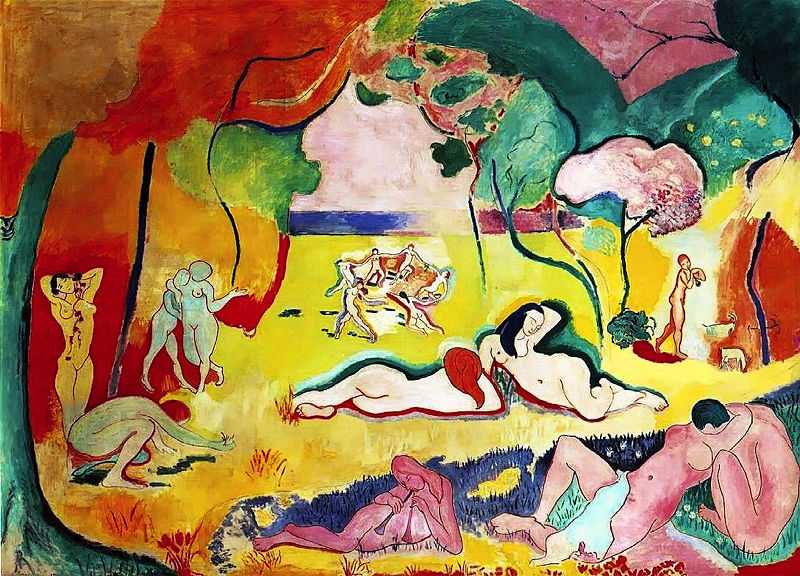

He borrowed from Japanese woodcuts in particular and ‘Joy of Life’ or ‘Le Bonheur de Vivre’ from 1905-06 is one such example of this style. The landscape is taken from a painting he made of Collioure in the south of France but the overriding impression is not of a realistic landscape but of the flatness of the work, in keeping with the Japanese style.

The condensed composition with simple line figures follows the minimalist imagery of many Japanese woodcuts, though Matisse’s imaginary, idyllic composition is distinctly his own.

This particular work was on an enormous scale, composed of individual motifs to create a whole. His use of bold, intense colours shocked many viewers when the painting was displayed at the Salon des Indépendants. It showed a clear rejection of the Neo-Impressionist technique and a new direction for the artist.

The human form

As well as taking the Impressionist colour palette to extremes, Matisse also felt that the Impressionists had neglected the importance of the human figure in their paintings.

In his artworks, he sought to make the human figure central to his Post-Impressionist aesthetic and he manipulated the human form in many of his works. His depictions of figures ranged from angular, fragmented works to decorative, curvaceous bodies until by the end of his career, they were just symbolic.

This moved away from the Impressionist focus on capturing individuals at work and leisure, stripping the figures of their individual interests altogether.

3. Matisse and Post-Impressionism

Matisse soon took centre stage as a prominent Post-Impressionist artist, achieving recognition through his development of Fauvism.

The word Fauvism derives from the French ‘Les Fauves’, meaning ‘The Willd Beasts’. The Fauvist movement in France sought to break away from Cubism, another Post-Impressionist art form, in favour of a focus on colour.

Unrealistic colours

The Fauvist experiments with colour drew on the works of Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, among other Post-Impressionists, combining with the Neo-Impressionist techniques developed by Georges Seurat. Matisse developed his technique during the summer of 1905, which he spent in Collioure with André Derain.

Over this period, Matisse began using bright light and pure colours in his work, even if they did not represent the subject he was painting. He became known as the “chief Fauve”, with the word Fauvism coming to define the eclectic collection of artists who adopted elements of Matisse’s style.

Matisse believed that colour should be the foundation of painting, both as a means of expression as well as decoration. He viewed painting and art as a form of therapy, “a soothing, calming influence on the mind”.

In this way, he championed the aesthetic pleasure to be derived from art. Fauvism utilised blocks of pure colour and exposed canvas to construct images that were light-filled and romantic; he was was dedicated to the enjoyment of art.

Deliberate disorder

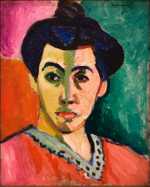

At the same time, it should be noted that many of Matisse’s paintings were deliberately disorderly, confusing the viewer’s eye in a somewhat unsettling way.

Much of his work was heavily criticised for its use of disjointed colour, as seen in the work ‘The Woman with a Hat’ from 1905. This painting depart from the conventional portrait style and shows the artist’s experiments with the Fauvist technique that went far beyond the purely decorative nature of artwork.

In this painting, he moves from an emphasis on balance and purity into a boundary-pushing exploration of colour in art.

Matisse and Picasso

In 1905, Matisse was also introduced to Pablo Picasso through the studio of Gertrude Stein.

The two artists quickly became friends. They parried to define the direction of French art after the death of Paul Cézanne and their rivalry was a key aspect of their relationship.

Where they aligned was in their experiments with the female figure and still life paintings, both of which were crucial elements of Matisse’s paintings throughout his career.

Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein would become a hugely influential character in the development of both Matisse and Picasso’s careers.

She collected hundreds of their artworks and encouraged her friends to do the same. Moreover, she welcomed the artists into her elite social circle, conducting them into the world of patronage and connecting them with a number of influential individuals.

It was the Cone sisters, Claribel and Etta Cone, who would assemble one of the preeminent collections of Matisse’s work in the world.

The end of Fauvism

Fauvism was to be relatively short lived among all of the Fauvist artists, including Matisse himself. They eventually moved away from the movement in the decade following 1906.

During this period, Matisse drew more heavily on influences from North Africa as a source of inspiration. This is evident in paintings like ‘Blue Nude’ or ‘Souvenir de Biskra’ from 1907, thought to be based on a sculpture he had seen during his travels to Algeria.

The female figure in this painting is depicted in an awkward pose, emphasising the outlandish curves of her body and her angular limbs that contrasts heavily with conventional, classical nudes. The blue hues further add to the unusual effect of the painting. Many critics have suggested this work is also a tribute to fellow Post-Impressionist Cézanne.

Matisse and the Pointilllists

Several of his earlier paintings also demonstrate the influence of Neo-Impressionist painters Paul Signac and Georges Seurat.

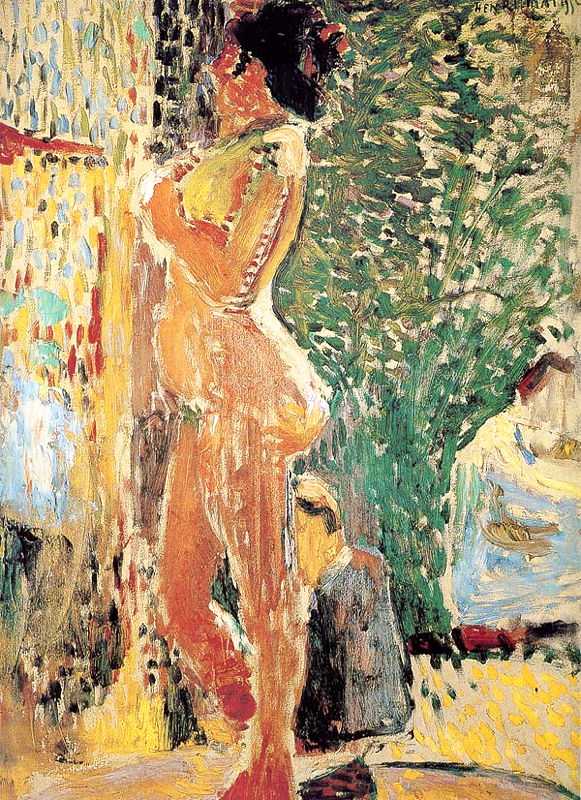

The painting ‘Luxe, Calme, et Volupte’ from 1904-05 follows the Pointillist technique of creating an image from distinct spots of paint. Where it differs from the Pointillist style is in the blocks of pure colour constructed by Matisse instead of building up colour through the technique of optical mixing.

Similarly, the nude figures in the scene have been outlined to give them greater emphasis, further diverging from the Neo-Impressionist technique.

This particular work was painted by Matisse while he was holidaying at Signac’s house in Saint-Tropez. The setting is most likely based on the view from his home. One can assume that the nude figures in the composition were added from the artist’s imagination, in the style of a traditional classical work.

On the left of the image, one woman is depicted clothed in contemporary dress which has been suggested to be Matisse’s wife, Amelie. The figures give the painting a dreamlike style, heightened by the dazzling colour palette.

Matisse’s Later Works

As Matisse grew as an artist, his work underwent several stylistic changes.

Much of his later work can be understood as a conversation with Cubism, as he sought to borrow from and break away from the most prominent movement in France at that time. There are many paintings in Matisse’s oeuvre where he appears to be wrestling with the influence of Cubism, none more so than in the painting ‘Bathers by a River’ from 1917.

Matisse returned to this painting several times over a period of around eight years, confronting Cubism by attempting to represent the human figure in a realistic way. At the same time, however, the figures are columnar and faceless, intercut with harsh lines so that it feels as though they are almost aching to morph into Cubist forms.

This work is now considered to be one of his most important masterpieces and Matisse himself named it as one of five most “pivotal” works in his career. It is on an enormous scale, originally commissioned by Sergei Shchukin, a Russian collector looking for decorative works to be displayed in his home.

The colour palette is restricted and there is something unsettling about the position of the faceless figures. Some critics have suggested that this darker work reflects the influence of the horrors of war on Matisse’s work as World War I was firmly underway by this point.

4. Matisse’s legacy

As well as painting, Matisse also developed a proficiency for sculpting.

He tended to create works using the human figure, demonstrating a profound interest in the human body and referencing ancient works in sculpture.

Works on paper

He further innovated in collage by using cut-out shapes of colour to create novel works in paper. This new medium pushed the artist to even simpler forms.

His experiments with paper are perhaps best known from his Blue Nude series from 1952, featuring nude figures made from abstracted cut-outs. The figures are simplified to extremes, depicted in Matisse’s distinctive raised arm pose that his became favourite motif.

The artist turned to works in paper in response to his debilitating health. After undergoing major surgery as treatment for abdominal cancer in 1941, he was forced to use a wheelchair, which limited him physically.

Paper cut-outs were more manageable than the large-scale monumental paintings he had created until this point. He also benefitted from the help of assistants who enabled him to continue working, including designing stained glass windows for the Chapelle du Rosaire in Vence, using the essentialised style developed from paper cutting.

World War II

Towards the end of his career, the effects of World War II began to take their toll.

Like many throughout Europe, Matisse struggled greatly with anxiety and the distress of his home being overtaken by Nazi invaders. He worked in a state of constant tension, describing to an interviewer towards the end of his life that every canvas began as a flirtation before ending as rape. His frustration led to desperation and his health worsened.

The revolutionary artist eventually died in November 1954, at the age of 84. He suffered a heart attack that killed him.

Legacy

Upon his death, Matisse was credited for his contribution to Modern Art in a career that spanned over a half-century. During this time, he championed the expressiveness of colour, pushing the boundaries of acceptable colour palettes and tones in art across a range of mediums.

Throughout his career, Matisse worked in tandem with fellow Post-Impressionist Picasso and the Cubist movement, borrowing from the style whilst reacting against it. Picasso and Matisse held a lifelong friendship and rivalry that would have a profound effect on both of their works.

Perhaps Matisse’s most prominent legacy, however, was his development and leadership of the Fauvist movement. The Fauvist artists were loosely aligned, each taking their own interpretation of the Fauvist emphasis on colour.

Nonetheless, they each shared an interest in intense, pure colour that would go on to drive Matisse’s work throughout his career.

Matisse honed the use of colour as a way of capturing the artist’s emotional state, making him a precursor to the Expressionist movement to come. Matisse is now regarded as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century and echoes of his work in painting and paper can still be seen, generations later, artworks today.