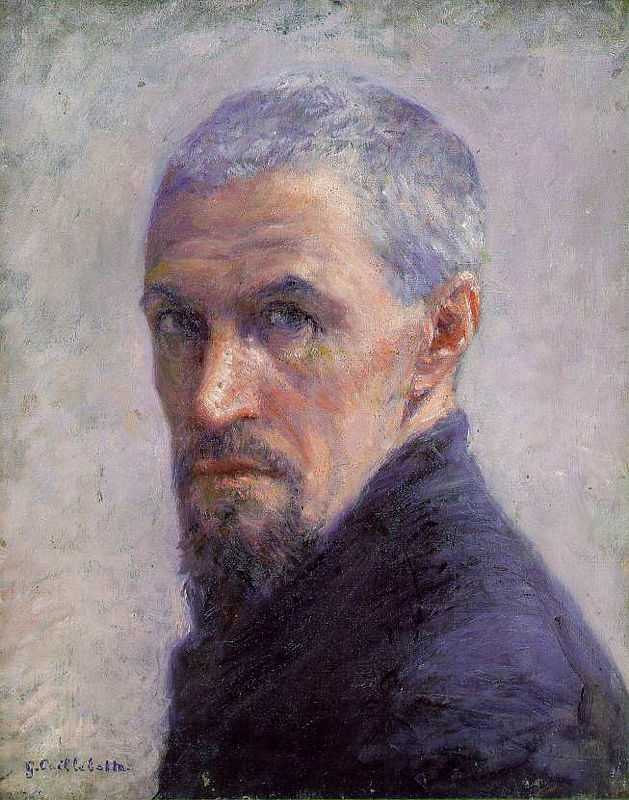

1. Caillebotte’s early years

Caillebotte did not embark on an artistic career until he was in his late twenties. Prior to his artistic education, Caillebotte studied law and engineering, obtaining his law license in 1870.

The Caillebotte family

His father, Martial Caillebotte, was the owner of a textile mill that supplied the French military, having inherited the family business from his own father. His mother, Céleste Daufresne, was Martial’s third wife as a widower. Little is know about Céleste, though she features in several of Gustave’s paintings including ‘The Luncheon’ from 1876.

The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war saw Caillebotte drafted into the army to fight in the conflict and he served in the Garde Nationale Mobile de la Seine between 1870 and 1871. At the end of the war, he decided to pursue a career in art.

Caillebotte studies art

His studies began under Léon Bonnat who was a Realist painter with a host of influential artistic connections. He then enrolled at the École des Beaux Arts in 1873.

Thanks to Bonnat, Caillebotte was introduced to Edgar Degas, Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir and others, which lead to him bringing a more impressionist visual vocabulary into his paintings.

These connections were also instrumental in establishing his status in the Impressionist movement and the wider Parisian art scene. He became an influential figure and had close ties with many of the most important artists of the period.

Caillebotte's inheritance

Shortly after beginning his artistic career, in 1874, Caillebotte’s father died. Just two years later, his brother René also passed quickly followed by his mother. This horrific loss left Gustave and his younger brother Martial as the only surviving members of the family. Consequently, the inheritance left by their father was divided by the two brothers. Caillebotte came into an enormous fortune.

He reached his artistic maturity as the Paris art scene was booming. This meant he was fortunate enough to miss the turmoil of the Franco-Prussian War and the fierce economic downturn that followed. Coming into his inheritance upon the death of his father gave him considerable freedom to work as he wanted to, painting and collecting without concern about commercial success.

2. Caillebotte’s patronage

Thanks to his substantial inheritance, Caillebotte is famous as a collector and an artist.

His family fortune meant that he was able to purchase works by prominent Impressionists including Monet, Renoir, Pissarro and many more. In this role, he became one of the most important promoters and supporters of the Impressionist movement, providing considerable financial backing.

In many ways, Caillebotte’s collection of Impressionist art overshadowed his own artistic achievements. On top of the core group of Impressionist artists he patroned, Caillebotte also supported the Post-Impressionist, Fauvist and Symbolist movements.

However, he was also highly selective. He was extremely loyal to artists he respected but did not associate himself with many other prominent individuals including Georges Seurat or Paul Gauguin. Whether this was a personal or business-led decision is unknown.

Whilst the funding Caillebotte provided was vital for sustaining many Impressionist artists, he also contributed in his organisation and guidance of the movement. He oversaw key exhibitions of the Impressionists’ works, carefully curating what he saw as the best examples of Impressionism, which included his own works.

In doing so, he sustained the movement and propelled it forward, even as the impressionists faced severe criticism from the Parisian mainstream.

3. Caillebotte’s Impressionist works

Let’s not forget that Caillebotte was a painter too. He shared the Impressionist movement’s emphasis on depicting modern, everyday life, capturing the movements of people and events as they happened.

This unifying theme showed itself in Caillebotte’s work through his focus on Paris in the 19th century. His early works feature Parisian scenes in the newly developed city, displaying broad, bright streets lined with modern buildings.

Haussmann's Paris

This was Napeoleon III’s ambitious plan to remodel Paris into a grand capital. Largely conceived and led by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, the redesign favoured a clean aesthetic and standardised apartment blocks.

In doing so, he laid waste to the medieval layout and buildings that had stood before, creating a confident, ordered city in its place. Many people mourned the loss of the old Paris but Impressionist artists including Caillebotte and Pissarro embraced the artistic views that the new city afforded. Caillebotte’s works use realism to show the viewer the orderly, grand city that Paris had become.

The Pont de l'Europe

One painting, ‘The Pont de l’Europe’ from 1876, is a shining example of his work celebrating the modern Paris that had been constructed during this era. Caillebotte’s painting depicts the enormous iron bridge, hinting at his engineering background.

This iconic feature of the new Parisian landscape was a subject he returned to multiple times. Thanks to Caillebotte’s eagle-eyed style, his paintings are now regarded by art historians as a valuable insight into the city’s radical transformation and the social implications of the changes.

The Floor Scrapers

As well as depicting the urban landscape, Caillebotte experimented with a broad range of subjects from studies of flowers to landscapes to portraits. His paintings of figures are some of his most famous. ‘The Floor Scrapers’ from 1875 was originally rejected from the Paris Salon as it was seen as too raw and even ‘vulgar’. Nonetheless, it is a distinctive and striking work, featuring three workmen on their hands and knees, toiling on the wooden floor of a Parisian apartment.

This is one of the first pieces to show working-class individuals in an urban landscape, rather than peasants in rural France. The academic style is clear and exact, lending the composition greater power. The workers’ naked torsos contrast with the delicate ironwork in the window and the clean lines of the stylish panelled walls.

This painting is also interesting for its bold perspective. The viewer is positioned above the men, looking down on them. This cinematic vantage point echoes the status of the workers, whilst borrowing from the tilted vantage points of Japanese art, which was enjoying a boom in popularity in Europe during this period.

Furthermore, the careful attention paid to the natural light from the window behind the men shows Caillebotte’s sensitivity to the Impressionist style. Caillebotte showed this work at the Third Impressionist exhibition in 1877, having also exhibited at the Second Impressionist exhibition the previous year. He contributed seven more artworks to the show. He also helped to finance and organise it.

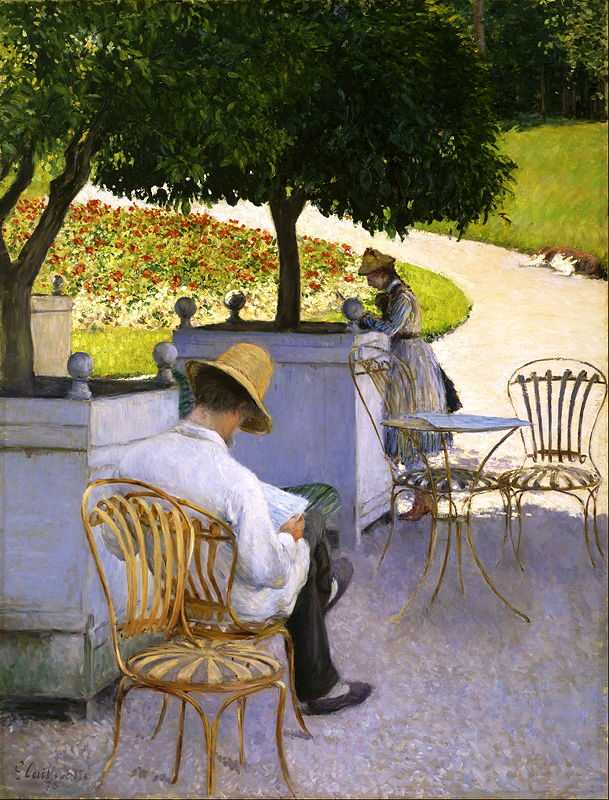

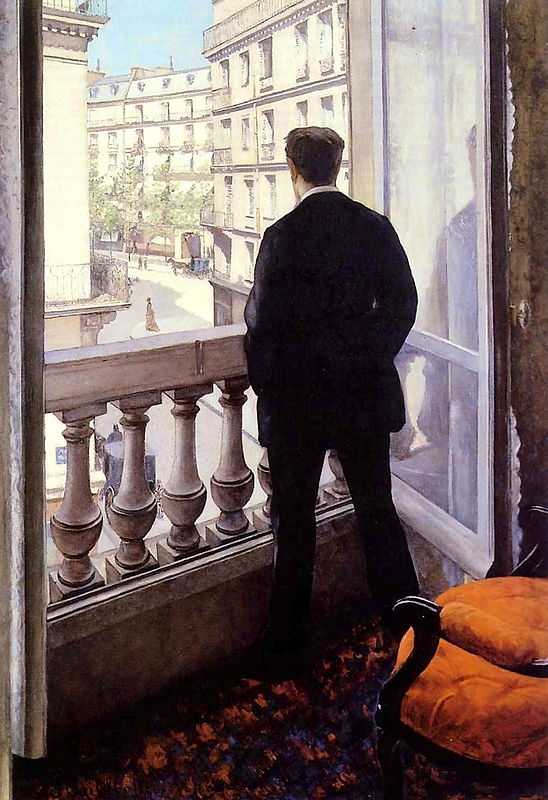

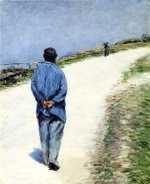

The City

Despite his focus on figures, Caillebotte’s works always return to the city. In another painting, a man stands looking out of a large window. In the streets, the Rue de Lisbonne is clearly seen, a modern street that epitomised the new Paris. The faceless figure is the artist’s brother, René. An elegant, orange-coloured upholstered chair is partially shown behind him.

The colour of this fabric is the most radical aspect of the composition as the black-suited individual stands motionless and the buildings are fixed and formal. However, it also denotes the drama of the city’s redesign and the stark divide between the old and the new, the wealthy and the poor. The figure is both powerful and lonely, epitomising the Modern Man but his true emotions remain out of sight for the viewer.

4. Caillebotte’s nudes

It is worth noting that Caillebotte’s figures were also exceptional in a different way - he painted both male and female nudes in unidealised and impromptu poses.

Whilst female nudes were well-known to the art establishment and the Impressionists began to push the boundaries of nude painting, male nudes were still largely unseen during this period.

One notable exception is the work of his earliest teacher, Bonnat, who also represented male nudes in styles that cannot be considered classical. Key examples include ‘The Barber of Suez’, painted by Bonnat in 1876.

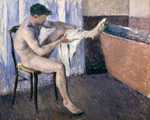

Man at His Bath

Caillebotte’s work ‘Man at His Bath’ from 1884 is a candid composition of a man drying himself after bathing, with wet footsteps still evident on the floor. The large-scale painting, with the male figure almost life size, was extremely shocking to the public when it was exhibited in 1888. Even then, it was four years after the work had officially been completed.

‘Man at His Bath’ sparked outrage and fervent critique from the public as it portrayed a nude modern man in an ordinary setting rather than a romantic, classical scene.

Nude on a Couch

The perspective of the work gives the viewer an intimate insight into the bathroom and the buttocks and the genitals of the male figure are clearly visible. As with Caillebotte’s female nudes, including ‘Nude on a Couch' from 1880, we become voyeurs, drawn into the private space of the figure.

However, instead of a woman lying bare on a couch, in this work we are spying on the muscular form of a man at his ‘toilette’. In doing so, the viewer enters into a privileged private space with the male sitter. Here he is stripped of the suits, top hats and status that is enjoyed by most male subjects from art at this time. He is exposed.

The Male Form

This work and others including ‘Man Drying His Leg’ from 1884, are set apart from better known Impressionist nudes because they feature the male form. Though artists such as Degas, Renoir and Cassatt painted nudes, these works only featured women, albeit in untraditional poses.

Images of nude men were extremely rare and marginalised during the 19th century and even now many scholarly works discuss the paintings with a conservative and self-conscious turn of phrase that is missing from analysis of similar female nudes. Caillebotte’s in-depth studies of the male form are considered unique in avant-garde art.

5. Caillebotte’s later works

Caillebotte settled permanently in Petit Gennevilliers in 1888 where he and his brother Martial had bought an estate in 1881.

This quaint village became popular for many Impressionist artists thanks to its proximity to Paris. It was also known as a fashionable retreat for wealthy Parisians, offering a slice of country life without the need to travel too far from their homes. Caillebotte expanded the estate and spent time painting his picturesque property and enjoying country pursuits until his death in 1894.

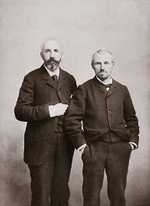

Martial's Photography

Comparisons have been drawn between Caillebotte’s paintings and Martial’s photography. The two brothers shared a great number of hobbies and moved in the same circles, living together in their Petit Gennevilliers home. As such, the crossover is perhaps unsurprising.

Caillebotte’s favouring of cropped persective and realism is certainly reminiscent of photographic works. This is especially true of one of his most famous paintings, ‘Paris Street, Rainy Day’ from 1875.

Paris Street, Rainy Day

In this scene, a sharp contrast is made between the figures closest to the viewer and those crossing the street in the background, prompting attendees of the 1877 exhibition where it was shown to draw comparisons with photography. It’s worth noting that at the time this stylistic technique was extremely uncommon.

In general, Caillebotte's later works are looser and more vibrant than his earlier paintings. His brushwork becomes heavier and his art takes on a domestic feel as in ‘Le Jardin Du Petit Gennevillier, Les Toits Roses’ from 1891 and ’Dahlias, Garden at Petit Gennevilliers’ from 1893. There is also a clear influence of Japanese art, in keeping with wider trends in Western art.

Later Works

‘Chrysanthemums in the Garden at Petit-Gennevilliers’ from 1893 demonstrates Caillebotte’s experimental style, both in the subjects he chose to focus on and his compositions. This still-life piece features a flurry of flowers, painted in a naturalistic palette and dusted by natural light entering the scene from above. However, the unusually flat composition is reminiscent of Japanese woodcuts.

By the 1890s, Caillebotte’s painting had tailed off considerably. He painted infrequently, choosing to focus more on gardening, collecting and building yachts. He died suddenly from a stroke in 1894, collapsing in his garden in Petit Gennevilliers. Renoir was the executor of his estate.

6. Caillebotte’s legacy

When Caillebotte died, he donated a large portion of his art collection to the French Government.

They were hesitant to accept, demonstrating the controversy that still remained between the art establishment and the Impressionist movement.

The Caillebotte Room

Nevertheless, the Caillebotte Room at the Luxembourg Palace in Paris opened in 1897. This was the first exhibition of Impressionist paintings in a French museum and represented a remarkable leap forward for public acceptance of the Impressionism.

Now famous works like the 1876 ‘Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette’ by Renoir were exhibited in an official space for the first time. However, it was still only a fraction of the total bequest.

The collection was then added to and became the Impressionist collection at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. The majority of the unclaimed works were bought by Albert Barnes, an American art collector, and now form the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia in the U.S..

Caillebotte's Generosity

Much of Caillebotte’s own artworks never made it into the public sphere, remaining in the possession of his family. He was known for his generosity, regularly gifting his paintings to friends and fellow painters. Consequently, many of his works and the extent of his artistic legacy is only now being revealed as paintings held in private collections are put up for sale.

Road to Recognition

This lack of access meant that his considerable talent largely went unnoticed until the later 20th century. Re-evaluations of his paintings have led to many art historians highlighting the intersection between realism, impressionism and post-impressionism in his works. Caillebotte’s art is now understood to epitomise the end of the 20th century in French art, combining the most prominent movements from the time.

Despite his considerable wealth, Caillebotte is also notable for his unflinching depictions of the class divide in Paris. His unusual perspectives heightened the power of his works and went on to inspire other artists to do the same. Caillebotte is now regarded as a highly ambitious impressionist artist whose paintings we are still discovering in their unabashed and unusual entirety.