1. Cezanne's early years

Paul Cezanne was born in Aix-en-Provence, in southern France, on 19 January 1839.

His father was an entrepreneur, running a hat-making business at the time of Cezanne’s birth (called Cezanne and Coupin), and going on to found the Cezanne and Cabassol Bank in 1854. Cezanne’s parents married in 1844, just after Cezanne turned five.

Education and Paris

Cezanne entered the local College Bourbon in 1852, making friends with Emile Zola and Baptistin Baille. Zola was to become a writer and art critic and Baille a scientist.

Cezanne, Baille and Zola were known as "the inseparables". They played in the Provençal countryside, read poetry and classics, and carried out scientific experiments. But all this ended when Zola left for Paris in 1858.

Interesting fact...

At about this time, Cezanne and his father quarreled. The problem was that Cezanne Snr wanted his son to study law, forbidding him to follow Zola to Paris until he passed his law exams. And so Cezanne started his legal studies in 1858.

By 1861 Cezanne had dropped out and had persuaded his father to let him travel to Paris. He enrolled at Suisse’s studio while he tried to obtain admission to the Ecole des Beaux Arts. But he was rejected and, his fragile confidence destroyed, he fled back to Aix to work in his dad’s bank.

Cezanne found being a bank clerk too boring and was back in Paris the next year; he soon became a copyist at the Louvre (ie an art student authorised to copy the works of old masters).

1863-70: Salon rejections

Cezanne submitted a work to the Salon in 1863. It was rejected and Cezanne exhibited, together with works produced by Manet and Pissarro, at the Salon des Refusés.

More rejections were to follow. In 1865, Cezanne’s first important attempt at still life—Still Life with Bread and Eggs—was turned down by the Salon. The next year, a portrait of Antony Velabregue was rejected; one juror commented that it appeared to be

“painted with a pistol."

In 1870 Cezanne submitted another portrait to no avail, this time of his dwarf friend Achille Emperaire.

Cezanne put on a brave face:

“Institutions, stipends and honours are made only for idiots, pranksters and rogues ... I don’t give a damn”.

But the truth was that the rejections cut him to the quick.

Cezanne's dark period

The period 1861-70 represents Cezanne’s so-called "dark period": his palette was dark; his themes were violent or erotic; and he often applied paint using a palette knife and not a brush. A typical work was Cezanne’s shocking painting entitled The Murder (1870, pictured). Another, from 1867, was called The Abduction.

It was not until about 1870 that, encouraged by Pissarro, Cezanne adopted the impressionist style by lightning and brightening his colour schemes and painting with broader brush-strokes.

2. The impressionist exhibitions

Cezanne took part in two of the eight impressionist exhibitions, in 1874 and 1877. He earned nothing but ridicule and abuse.

1874: The first impressionist exhibition

By 1874, the impressionists—as they would come to be known—had had enough of being rejected by the Salon and decided to hold their own independent exhibition. But Cezanne was nearly excluded.

Of Monet, Degas, Sisley, Berthe Morisot, Renoir and Pissarro, only Pissarro was in favour of his inclusion.Manet, who was also consulted, was also against, describing Cezanne as a "buffoon".

In the end, Degas settled the issue by proposing that a string of fashionable established painters such as Boudin be included. The group thought that they could not, in these circumstances, exclude one of their own.

Interesting fact...

Part of the problem was that one of Cezanne’s three proposed submissions was downright bizarre. A Modern Olympia was meant to be a witty interpretation of Manet’s Olympia (a painting which shocked the art world in 1865). But Cezanne’s interpretation (pictured) is a mess of what appear to be partially melted plasticine figures.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Modern Olympia received the harshest criticism. One critic said that Cezanne was a:

“sort of madman, painting in a state of delirium tremens”.

By contrast, his other entries—The House of the Hanged Man at Auvers and Landscape: Auvers, which are more traditional impressionist fare—got off relatively lightly.

1875-77: Victor Chocquet and the third impressionist exhibition

Lack of funds meant that there was no impressionist exhibition in 1875, but a number of the group decided to hold an auction of their works at the Hotel Drouot. It was at this time that the group acquired a number of collectors. They included a tax inspector with a small private income called Victor Chocquet.

Chocquet was initially a big Renoir fan, but Renoir selflessly introduced him to Cezanne’s work.

Interesting fact...

When Chocquet bought a small Cezanne nude he was worried about what his wife would think and so Renoir pretended that it belonged to him!

Chocquet got in well with Cezanne and provided him with both financial and emotional support: he even stood beside the 16 works Cezanne showed at the third impressionist exhibition held in 1877, the only other exhibition that Cezanne was to participate in, and sought to explain their complexities to often baffled onlookers.

The reviews of the third exhibition were again unfavourable. It was at about this point that Cezanne drifted away from the impressionist group, declining to participate in any further group exhibitions, and retreating to Provence to focus on paintings of its landscapes and Mont Saint-Victoire.

3. The 1880s: Cezanne paints Provence

Cezanne matured as a painter during the 1880s. He also managed to get accepted at the Salon, for first and only time in his career.

1880 onwards: Mont Saint-Victoire and Provence

From 1880, Cézanne repeatedly painted a 1,011 metre Provençal mountain called Montaigne Sainte-Victoire.

In total, he produced 44 oil paintings and 43 watercolours of this impressive rock. Cezanne’s strong feelings for the mountain can be seen from the following quote (taken from Joachim Gasquet’s 1921 biography):

“Look at Ste-Victoire. What elan, what an imperious thirsting after the sun, and what melancholy, of an evening, when all this weightiness falls back to earth.”

Cezanne’s paintings of Sainte-Victoire often use distinctive horizontal brush strokes and show the mountain from a number of viewpoints. They include vivid orange, green and blue colour patches and often also pine trees, the Chateau Noir and the quarry at Bibemus.

Cezanne also painted a number of seascapes over this period, including the beautifulGulf of Marseilles Seen from L'Estaque(pictured). This work perfectly captures the intense blues of the sky and sea, and the clarity of light, found in Provence.

The 1882 Salon

Cezanne was only once accepted by the Salon.

In 1882, he submitted a work entitledPortrait of M.L.A.The acronym stood for Monsieur Louis-Auguste, Cezanne's father. And the painting is similar to a work that Cezanne produced many years earlier, in 1866, entitledThe Artist’s Father, Reading L’Enevement.

Interesting fact...

Cezanne did not use his father’s surname and described himself as a student of Antoine Guillemet (a member of the jury). This was a ruse: the two men were friends, having studied at Suisse’s academy a decade previously! But it persuaded the Salon's jury to accept the painting.

4. Cezanne's Personal Life

Cezanne was a difficult man who had a complicated personal life.

The Prussian War

1870/1 saw France defeated in the Prussian war. Cezanne was called up but refused to fight. He spent the conflict in a fishing village close to Aix called L’Estaque, hiding from the authorities.

Cezanne was not the only impressionist to avoid the conflict: Monet travelled to London with his new wife and baby son. In contrast, Manet joined the army and defended Paris when it was besieged by the Prussians; Renoir was called-up but saw no action; and Bazille was killed in battle.

Hortense and “little Paul”

Cezanne met Marie-Hortense Fiquet when she was working as a model in Suisse’s studio in 1869. The two formed a relationship and had a son, Paul, in 1872.

Cezanne’s relationship with Hortense was never easy, partly because Cezanne hid the existence of his relationship with Hortense from his father for nine years.

Interesting fact...

Cezanne’s father only found out about their child when he read a letter to Cezanne from one of his patrons, Victor Chocquet. Chocquet made the mistake of referring to Madame Cézanne and “little Paul”!

Cezanne finally married Hortense in 1886, by which stage he had lost his romantic feelings for her. The two appear to have become hitched for the good of their son.

Cezanne and Hortense became estranged in the 1890s. By that time Cezanne had produced 29 portraits of Hortense-which suggests that he had genuine affection for her. But he later cut Hortense out of his will, leaving his entire estate to his son.

1886: Zola’s L’Oeuvre

In 1886, Zola published the fourteenth book in the Rougon-Macquart series he had been writing, entitled L’Oeuvre (the Masterpiece). The central character was Claude Lantier, a brilliant artist doomed to failure.

Zola sent a copy to Cezanne who recognised a number of parallels between himself and Claude. He was extremely upset, returned the book with a letter full of feeling, and severed all ties with Zola.

Cezanne’s extreme reaction can be understood. The following are extracts from L’Oeuvre:

“The break between Claude and his friends had slowly widened. His painting they found so disturbing ...."

"Claude had somehow lost his foothold and, as far as his art was concerned, was slipping into madness, heroic madness ....”

5. 1890-1906: Cezanne’s final period

Success came for Cezanne fairly late in life, starting with the solo exhibition of his works put on by Vollard in 1895.

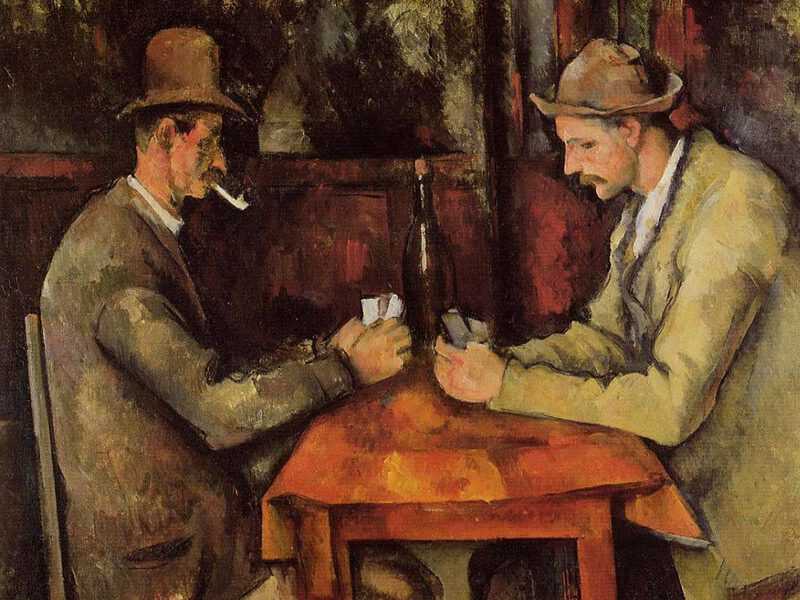

1890-5: The Card Players

Cezanne’s Card Players are probably his most famous works today.

In all, Cezanne painted five versions of the Card Players. They each depict local Provencal labourers intensely focussed on a game of cards, seemingly oblivious to everything around them. Two of the versions, probably those produced first, show three card players, with the remaining versions depicting only two.

The works are fascinating for a number of reasons:

- Most participants wear hats, perhaps a nod to Cezanne’s father’s first business.

- The colour blue, a Cezanne favourite, features heavily.

- The works become increasingly minimalist, with structure given in the last in the series by the central table and wine bottle.

- The proportions of some of the figures seem distorted—check out the long arms and small heads of some of the participants in the two-player versions.

One version of the Card Players was sold for a then world-record $259 million in 2011.

1895: Ambroise Vollard to the rescue

Born in 1866, Ambroise Vollard obtained a law degree in 1888 but wanted to be a picture dealer. He became a clerk for an art dealer and, in 1883, established his own gallery on Rue Laffitte. The next year, he bought two Cezannes.

Shortly thereafter, in 1885, he bought most of Cezanne’s output of the previous three decades to put on a one-man exhibition. It was a considerable commercial success, and Cezanne’s reputation starts to grow.

This can be seen from the following chronology:

- In 1897, the National Gallery in Berlin acquired a Cezanne.

- In 1899, when Victor Chocquet’s estate sale was held, Cezannes fetched up to 4,000 francs.

- In 1903 Cezanne exhibited in Vienna, Paris and Berlin.

- 1904 even saw a whole room devoted to Cezanne's works at the Salon D’Automne, an annual art exhibition held in Paris. Thirty-one works were displayed, covering the full spectrum of Cezanne’s output (portraits, self-portraits, sill lifes, landscapes, and bathers).

1895 onwards: The Bathers

Cezanne had painted bathers in his impressionist period and returned to this theme later in life. By contrast with his earlier works, however, his later bathers are either all female or all male. In addition, the bathers of his later works are not differentiated: their faces are coarsely drawn and appear to be exactly the same.

Cezanne was trying to capture the human form in nature with these works, often with some sort of geometrical structure. The most famous painting, the Large Bathers, has a triangular structure (often used in Renaissance works to give a picture gravitas).

Interesting fact...

Remarkably, especially given the seemingly broad brush strokes used, it took Cezanne seven years to complete the Large Bathers (1900-1906). The other striking thing about the work is its huge size: 211 cm by 251 cms. Cezanne had to have a slit made in his studio wall to remove it!

1906: Cezanne’s death

On 15 October 1906, aged 67, Cezanne was caught in a thunderstorm while painting in a field. He collapsed and was taken home by a passer-by. He contracted pneumonia, to which he succumbed on 22 October 1906. Cezanne spent the intervening week getting out of bed to add finishing touches to the watercolourStill Life with Carafe, Bottle and Fruit.

Cezanne is buried at the St Pierre cemetery in Aix.