1. Morisot’s early years

The granddaughter of famous Rococo painter Jean-Honore Fragonard (1732-1806), Morisot grew up with art in her life.

Her father studied at the Ecole de Beaux Arts in Paris before becoming a high-ranking government official.

Berthe was one of four children - three girls and a boy. Her parents firmly supported her artistic ambitions and built Berthe and her sister Edma a studio in the garden of their family home.

This support is in stark contrast to the parents of Edouard Manet and [Paul Cezanne](/paul-cezanne-biograph, who discouraged their children's artistic ambitions.

Morisot's mother

Berthe's mother, Marie Cornélie Morisot, was adamant that her daughters should pursue a career as professional artists if they wished to, despite the stir this would cause in the upper-middle class circles they moved in. (Berthe was born at a time when women were expected to look after the home and not pursue art beyond being a lady’s pastime.)

Interesting fact...

Marie Morisot also went to every exhibition of her daughters' work and reported back on the critiques she overheard from viewers in order to help them refine their art further.

Berthe and Edma were enrolled in the Ecole Des Beaux Arts for three years, from 1856 to 1859. Berthe decided from an early age that she wanted to be an artist and applied herself with great passion at art school. From 1862 to 1868, she worked with Camille Corot (the leading landscapist of the Barizon school) who provided guidance and informed her stylistic development.

The rise of both women was disrupted in 1869 when Edma married a naval officer and took a step back from her painting. At this point, Berthe vowed to focus on her career and remain single for the rest of her life.

Manet and Morisot

Working as a copyist at the Louvre in Paris, Morisot met Henri Fantin-Latour, a French painter who then introduced her to Édouard Manet.

From 1868, Morisot and Manet became very close friends. Persuaded to model for one of his artworks, Manet eventually painted 11 portraits of Morisot over the course of their friendship.

Interesting fact...

Some suggest that Manet and Morisot were more than friends. It is true that Manet painted Morisot in what were at the time intimate positions (eg lying backwards over a couch in Le Repos). It is also true that Berthe had Edma destroy some of her letters referring to Manet. But we are unlikely to ever know for sure whether Edouard and Berthe's relationship was sexual in nature.

Morisot married Manet’s younger brother, Eugène, in 1874. Though Eugène was also an aspiring artist, he gave up his career so that she could pursue hers.

Morisot's Style

Morisot’s style developed in parallel with Manet, both artists experimenting with the effects of light in their works and rough, expressive brushstrokes. Morisot largely focussed on painting women and children, often in the home. This private setting allowed her to depict the parts of ordinary life that many other Impressionists missed out on - her works are a snapshot into a personal sphere.

However, to say that she was merely a painter of domestic subjects is to reduce her work to a stereotype. Morisot produced a number of paintings that show the energy and movement of the public sphere as well, including vibrant boatyards, harbours and the banks of the River Seine.

2. The Impressionist Exhibitions

The Impressionist exhibitions were first conceived as a reaction to the Paris Salon and its restrictive judging process for artworks.

Though many of the Impressionists had their paintings rejected from the Salon time and time again, this was something that Morisot never struggled with.

From the age of just 23, two of her landscape paintings were chosen for the 1864 Salon and critics praised her style and ability. This was an outstanding achievement for a young woman at this time.

The first exhibition

Morisot enjoyed success in the Salon right up to 1873, when on hearing that the other impressionists were failing to have their paintings accepted, Morisot stated that she would not exhibit her work there again.

Instead, she aligned herself with the impressionist movement, participating in seven of the eight impressionist exhibitions between 1874 and 1886. Her sole reason for missing the fourth exhibition in 1879 was due to the birth of her daughter, Julie.

In addition to her submissions, Morisot also contributed to the organisation and the costs of staging the events.

Interesting fact...

Only Camille Pissarro exhibited in more impressionist exhibitions than Morisot (he submitted to all eight).

The progression evident in the works Morisot exhibited over the eight exhibitions is testament to her unceasingly experimental style. The first exhibition of 1874 featured 30 artists with 165 works. Here, Morisot displayed one of her largest works, ‘The Mother and Sister of the Artist’ from 1869-70. She also chose to hang eight more paintings, including watercolours and pastels.

Misogyny?

The development of this particular painting is an interesting one.

The story goes that prior to submitting it to the Salon in 1870, Morisot appealed to Manet to give his opinion on the piece. Instead of giving the verbal critique she expected, Manet instead began painting over the black fabric of the Mother’s dress.

Many descriptions of this moment credit Manet with rendering the artwork a success, negating Morisot’s role in painting every other aspect of the work. Indeed, whilst beautifully painted, the black dress is a background part of the painting.

However, at the time Morisot was horrified, telling her mother that she would

“rather be at the bottom of the sea”

than exhibit this work at the Salon.

The painting was well received but continued to cause Berthe distress for many years onwards. The interaction offers a glimpse into the challenges Morisot faced throughout her career.

The Second Exhibition

The second impressionist exhibition of 1876 featured far fewer artists, with only 20 exhibiting, but a larger number of works at 252 pieces. They included the striking Hanging the Laundry out to Dry (pictured).

One scathing critic described the show as

“five or six lunatics—among them a woman—a group of unfortunate creatures."

Morisot was a determined and energetic figure in the the exhibitions but she was continually discredited due to being a woman.

Later Exhibitions

As noted above, Morisot took part in all but one of the later exhibitions. Her most important works were as follows:

- Third Exhibition: the Psyche Mirror (pictured).

- Fifth Exhibition: Young Girl in a Ball Gown.

More Misogyny?

Morisot's name was omitted from the publicity posters for the fifth exhibition in 1880. Degas stated that this was ‘Idiotic’ as all 16 of the male contributors were listed. Marie Braquemond and Mary Cassatt, the two other female painters in the exhibition, were also missing from the poster.

The final Impressionist exhibition in 1886 was organised almost entirely by Morisot. Unfortunately, her influence is rarely recognised.

An earlier quote from Manet is especially revealing:

“This woman’s work is exceptional. Too bad she’s not a man.”

3. Women, Children and Windows

Morisot’s wealthy upbringing meant that she was not as reliant on making money from her paintings in the way that many of the other impressionists were.

Unlike Renoir and Pissarro, who had financial worries for much of their careers, Morisot was able to be more tactful in the way in which she exhibited and sold her artworks. She used fashions and the tastes of collectors to inform a lot of her compositions.

Morisot's garden paintings are one such example of this commercial aptitude. The most important collectors of the day recognised her works and purchased them. However, she often sold her paintings at a lower rate than many of her male contemporaries, a source of great annoyance to her throughout her life.

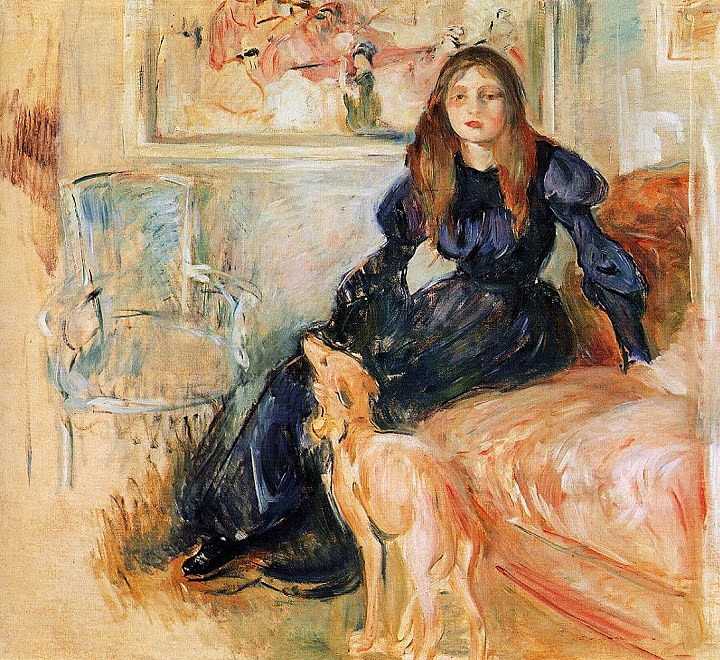

Women and Children

The so-called garden paintings feature mostly women and children, situated in gardens and in front of windows with dense greenery and flowers behind. These paintings mix a feeling of stillness and silence with energy and movement, both in the natural elements and the clothing of the figures.

In paintings such as ‘Girl by the Window’ from 1878, there is a sense of restlessness and even wildness that is conveyed, even whilst the sitter is seated serenely.

Windows

Windows were a recurring theme in many of Morisot’s works, used to frame her figures and the space behind them. She used windows as a metaphor for transparency, seeing through to the world beyond, as well as into the mind of her subject.

Works like ‘In the Country (After Lunch)’ from 1881 and ‘Red Haired Girl Sitting on the Veranda’ from 1884 also feature glass objects in the composition that mimic the glass of the windows, merging the inner and outer worlds of her paintings into one.

In the former work, the woman’s figure is partially transparent. Her abdomen melts into the garden scene behind where she is sitting. This powerful effect is lost in reproductions of her paintings, both in print and digital forms. Some critics have suggested that this is one reason for her lack of fame - the impact of her artworks is lost unless you are able to see them in person.

Vulnerability

Many of her paintings have a vulnerability and authenticity to them that makes them particularly captivating. The viewer spies on a ‘Woman At Her Toilette’ (1875-1880), looking at her looking at herself in the mirror as she fixes her hair. However, the eroticism and all-pervasive male gaze that features in similar works by male artists is absent, replaced instead by an atmosphere of introspection.

Morisot was masterful at using white to accent her works. She used white brushstrokes to signify ripples, mirrors, skin, fabric, the sky, air and sunlight, using shades of white in an extremely expressive way. She created emotional works like ‘Le Bercau’ or ‘The Cradle’ from 1872, depicting a mother, her sister Edma, looking down at a baby asleep in a cradle covered with white gauze.

The Cradle

This is one of her most famous works and the viewer follows the mother’s gaze through the transparent fabric. The work is given an ethereality as well as a feeling of immediacy. The dark colours of the woman’s hair and dress and the shadows of the room beyond contrast with the gentle innocence of the sleeping child and the wisps of fabric draping over the cradle.

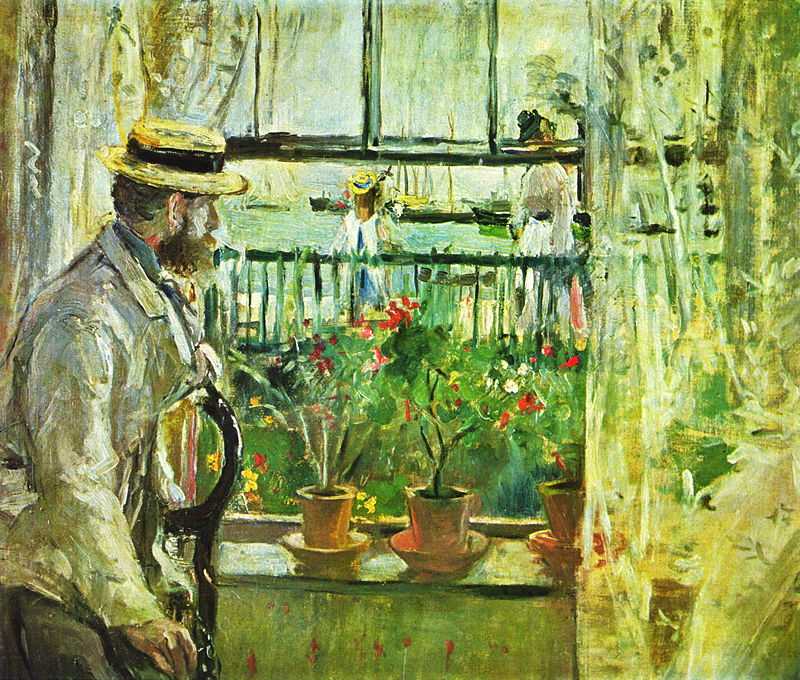

In all her works, there is a freedom to her painting style. Much of her brushwork is loose and unkept, making it extremely dynamic. It almost vibrates before the viewer’s eyes as in a painting of her husband and daughter - ‘Eugene Manet and His Daughter in the Garden’ - from 1883.

4. Morisot’s Later Works

Whilst Morisot’s work was firmly Impressionist in style for much of her career, there are some hints of a progression to Post-Impressionism later in her life.

Bright Palette

The bright palette of ‘The Harbour at Nice’ from 1881-82, for instance, plays with juxtaposing colours using small brushstrokes to create contrast and intensity. This technique was taken to extremes in the works of Seurat and Van Gogh to follow, who focussed heavily on colour contrast.

A Daring Nude

Similarly, paintings like ‘Reclining Nude Shepherdess’ from 1891 features vivid orange, violet and green colours that are very different to the muted tones of her earlier style, not to mention the contrast with her previously demure subject matter.

The naked figure, unclothed except for a headdress, was extremely unconventional for female artists at the time. Morisot drew on the styles of Renoir and Monet but innovated with her own form of expression, playing with the pose and the palette in this painting.

Abstraction?

Many of Morisot’s works feature gestures and brushstrokes that border on abstract styles. Known as “the angel of the incomplete”, paintings that she displayed as finished often have the air of a sketch, giving them a sense of vitality and experimentation.

She captured the essence of the scenes she depicted, painting faces in extreme detail and dispensing with unnecessary background details. Works like ‘Young Girl with a Vase’ from 1889 have a tactile feeling whilst the room around her is just a fleeting impression.

As she grew more confident in her abilities, Morisot became freer with her style and experimentation. There is a sense of fearlessness that comes through in many of her later paintings that is missing from the more restrained work of the mid-1800s. She pursued her own distinctly radical path, setting herself apart from the other Impressionists and pushing further towards abstraction.

5. Morisot’s legacy

Morisot’s death came suddenly and as a great shock to the Impressionist community.

Morisot's Death

Morisot lost her husband, Eugene, in 1893. Thereafter, she continued to paint and to encourage her daughter Julie to do likewise.

But Morisot was shaken to the core by the loss of her husband: her hair is said to have turned grey virtually overnight. It was in these circumstances that Berthe caught influenza, whilst nursing Julie, and died after a short illness in 1895.

A loss to the movement

The impressionist movement mourned the loss of Morisot's talent and her friendship.

In 1896, Renoir, Monet and Degas organised a memorial exhibition to mark a year of her death. Some 400 of Morisot’s works were hung. This exhibition is still the largest exhibition of her works to this day.

Morisot's gradual rise to prominence

Unlike the well-known greats of the Impressionist movement, Morisot was largely unknown to the public during her lifetime and for more than a century after her death. Her paintings were not shown with anywhere close to the same frequency and excitement of her male contemporaries during the early 20th century.

A 2012 solo exhibition of her work in Paris at the Musée Marmottan Monet was the first in more than 50 years.

Morisot now features at number 38 on the list of the most expensive impressionist paintings: her In the Country (After Lunch) sold for £6,985,250 in July 2013, giving it an adjusted price of over $13 million.

Feminist Scholars

It is only revisionist studies of the Impressionist movement by feminist scholars that have led to her name slowly surfacing from the shadows. Even so, there is still a dearth of information and recognition for her artwork that was so highly praised by her fellow Impressionists.

During her life and after her death, Morisot was not treated as an equal to other artists in the Impressionist movement. Her work is only now becoming known to a wider audience, more than 10 decades later. She is recognised today as one of the most important female painters of the 19th century, along with fellow Impressionist Mary Stevenson Cassatt, who she strongly encouraged in her career.

A poignant last word

A fearless innovator, Morisot struggled against the restrictions of the world in which she moved throughout her life. In 1890 she wrote in a diary entry that

‘I don’t think there has ever been a man who treated a woman as an equal, and that’s all I would have asked for – I know I am worth as much as they are.’