1. The artists and collectors

In total, 20 impressionist artists exhibited their work at the event.

It was agreed that the paintings should be hung in separate groupings for each artist so that each individual appeared distinctly.

Tactical hanging

To limit the outrage caused by the exhibition, they put the artists whose work was considered ‘easiest’ in the front rooms and the more ‘difficult’ artists in the back. This was designed to gently ease visitors into the exhibition, avoiding an assault of revolutionary work as soon as they walked in the door.

Edgar Degas enlisted the help of Berthe Morisot to coordinate the hanging of the paintings.

Morisot and Degas

Some of the most notable artists to exhibit in the Second Impressionist Exhibition were Morisot, Degas and Monet.

These artists were most highly praised in reviews and they each showed a large array of paintings. Morisot exhibited 19 paintings including ‘Hanging the Laundry Out to Dry’ from 1875, whilst Degas sent 24 works with ‘The Cotton Office’ and ‘In the Cafe’ among them.

Manet still out

Meanwhile, Monet displayed 18 works, which were duly chosen to go near the front of the exhibition. Édouard Manet chose not to exhibit with the group but there were several newcomers, including Marcellin Desboutin and Alphonse Legros, who did. Similarly, Camille Pissarro, Renoir and Alfred Sisley also contributed works.

Many pieces were further loaned by collectors such as Victor Chocquet and Jean-Baptiste Faure, a famous baritone. Faure had previously been a collector of works by Eugène Delacroix and Camille Corot among others, but on the advice of Paul Durand-Ruel, he had begun buying works by the Impressionists and Monet in particular.

Cezanne

Chocquet attended the exhibition every day and made it his duty to explain and defend his paintings to the public, especially the works of Paul Cézanne. “He turned into a kind of apostle” described Théodore Duret at a later date, expending enormous energy,

“in order to persuade them [visitors] of his convictions, to make them share his admiration and pleasure. It was a thankless task”.

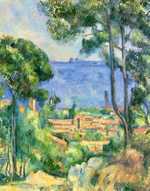

Cézanne chose not to attend the exhibition in person or send any of the works still in his possession, instead opting to stay in L’Estaque, a village in southern France where he was working on a series of landscape paintings.

Enter Gustave Caillebotte

Desboutin showed his etchings and dry points at the exhibition, as well as at least one painting. He was also one of the models for Degas’ infamous painting ‘In the Cafe’ from 1875-76, which left visitors to the exhibition appalled due its depiction of “low vice”, as George Moore described it. By far the most exciting artist in the Second Impressionist Exhibition, however, was another largely unknown figure: Caillebotte.

2. The role of Caillebotte

For the Second Impressionist Exhibition, Caillebotte acted as a central source of funding.

He had been introduced to the group by Monet and Renoir and he financed the exhibition almost single-handedly, using his inheritance from his father’s recent death. Caillebotte had in fact suffered a double personal tragedy, also losing his 26 year-old brother in 1874.

Caillebotte's crusade

These sudden and untimely deaths stirred in Caillebotte the feeling that his life might not last much longer and he invested a great deal of money and energy into staging the Second Impressionist Exhibition. His will drafted that year also included considerable funds designated to support future Impressionist exhibitions in the event of his death.

Caillebotte's art

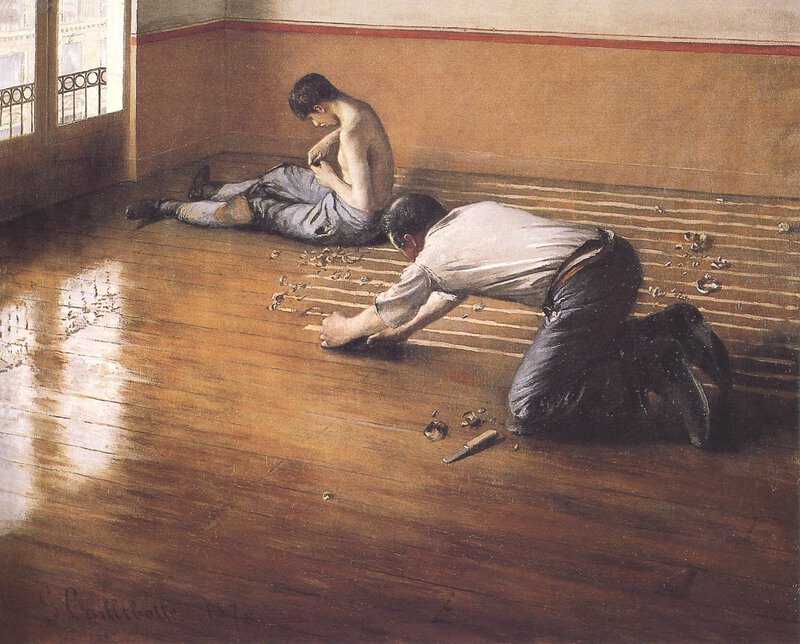

As well as acting as a crucial source of monetary support, Caillebotte also contributed eight paintings to the Second Impressionist Exhibition. By far the most important of these was ‘Les raboteurs de parquet’, ‘The Floor Planers’ or ‘The Floor Strippers’ from 1875. This impressive work was painted on an enormous scale and exhibits the academic style with which Caillebotte was taught to paint.

‘The Floor Planers’ is also one of the first examples of the urban working-class being depicted in art, though rural works and peasants had often been shown.

Caillebotte does not attach any moral message to his painting, he simply captures the scene with objective realism, from the tools to the gestures of the men and the strain of their muscles as they work on their hands and knees in a luxurious Parisian apartment.

Having previously been rejected by the Paris Salon due to talk of its “vulgar subject matter”, this painting was undoubtedly one of the stars of the Second Impressionist Exhibition. Visitors could not help but be arrested by the tableau and it was reported that people stood and stared at the work for some time. However, Émile Zola remarked somewhat ironically that it was a,

“painting that is so accurate that it makes it bourgeois".

The exhibition catalogue

Strangely, Caillebotte was not included in the exhibition catalogue, despite his central role. It has been theorised that this was because his inclusion was a later decision, but it may also point to rifts in the group that led to him being ‘overlooked’.

It is known that Degas was put out at losing his position as unofficial manager of the Impressionist Exhibitions thanks to Caillebotte’s involvement. On the other hand, it may have been a simple error on behalf of the printer, who also managed to spell the names of Monet and Sisley incorrectly.

3. The crowd

Attendance at the Second Impressionist Exhibition was considerably lower than for the 1874 first exhibition.

Nonetheless, a small crowd gathered to see the works displayed in the rue le Peletier. Paul Durand-Ruel had agreed to lend his gallery to the Impressionists for a month for the exhibition. Overall, some 252 works were hung, including two paintings by Frédéric Bazille, who had died in 1870.

Monet's Japanese Girl

Despite much mockery and criticism from the crowd, a few of the paintings sold. Monet’s ‘Japanese Girl’ from 1876 was sold for 2,000 francs, a high price for an Impressionist work at this time.

This rather satirical painting features his wife, Camille, wearing a blonde wig and a red kimono, posing smilingly with a fan raised against her face. The decorations on the striking kimono are rendered in extreme detail but the model’s face and hair are more of impressionistic, painted quickly and loosely.

Cezanne falls out with Monet

Whilst the painting was well-liked by visitors to the exhibition, Cézanne expressed his disapproval in private letters to Pissarro. He stated that if he exhibited with the Impressionists again, he would like to do so without Monet.

Cezanne saw Monet as having sold out in pursuit of commercial success, creating pretty pictures rather than progressive art. Similarly, the work was largely derided by critics in the press.

Degas' In the Cafe

Despite its controversial subject matter, Degas’ ‘In the Cafe’, later changed to ‘L’Absinthe’, was sold to a British buyer, Captain Henry Hill of Brighton. Hill lent the painting to the Third Annual Winter Exhibition of Modern Pictures in Brighton in 1876, where the title was changed to ‘A Sketch At A French Cafe’.

To some extent this demonstrates the perspective many visitors to the exhibition, who largely missed the concept of the paintings being finished works and instead saw many as mere sketches. Nonetheless, the sale provided Degas with much needed funds.

Renoir's La Promenade

The centrepiece of Renoir’s submission to the exhibition was ‘La Promenade’ from 1875-76. This lighthearted and fashionable piece, featuring two girls being shepherded by their mother through a park, was reportedly largely ignored by the public.

Much to Renoir’s disappointment, it was also criticised in reviews of the exhibition. Despite the lukewarm response during its first unveiling, Durand-Ruel eventually purchased the work. In his characteristic style of art dealership, he sold and bought back the painting several times in the following decades before eventually selling the painting to the wealthy American collector Henry Clay Frick.

Degas' The Cotton Office

Another talked about painting was ‘The Cotton Office’ by Degas. This painting demonstrated Degas’ familiarity with academic painting, despite its modern, industrial subject matter. Though it was exhibited at the Second Impressionist Exhibition, Degas had first conceived of the work whilst he was traveling in America.

His uncle owned a cotton business in New Orleans and Degas initially planned to sell the piece to a wealthy British textile manufacturer when he returned to Europe but was prevented from doing so as the cotton business declined sharply. Instead, he successfully sold the painting to the Musee des Beaux-Arts in Pau, France in 1878.

A small profit ...

Though overall attendance to the Second Impressionist Exhibition was not particularly high, the artists made enough money to pay Durand-Ruel 3,000 francs for the loan of the gallery and they each got back the 1,500 francs they had put into a group fund. On top of this, each contributing artist also got three francs. This made it a greater success than their previous exhibition.

When he heard the news of the modest gains made by the exhibition, Cézanne wrote to his father to tell him the good news. This expressive letter was perhaps an attempt to persuade his father that the exhibitions were a worthwhile venture after he had become indebted to him following losses from the First Impressionist Exhibition.

4. Critics of the Second Impressionist Exhibition

In the newspapers, the critical response to the Second Impressionist Exhibition was mixed.

Though many reviled the art on show and viewers were shocked by the picture of modernity portrayed by the Impressionists, some critics did provide the exhibition with a fair assessment.

However, many reviews came with caveats and dismissals peppered in amongst their praise.

Duranty

Edmond Duranty, writing in Paris, published a long and glowing review of the exhibition. He then went on to publish his own pamphlet titled ‘La Nouvelle Peinture‘ or ‘The New Painting’ which stretched to 38 pages. Paid for out of his personal funds, he described the movement’s central tenets in detail, telling the public about the extraordinary new way of painting light and capturing everyday life.

However, he also stated that he believed some of the artists were rather “too visionary”.

Some readers suspected that he had been enlisted by Degas to produce a positive review of the show as he paid much attention to his paintings in particular, above the other artists. Indeed, the two had earlier become friends over a shared interest in depicting daily life.

Henry James

Back in the US after a visit to Paris, Henry James reviewed the exhibition for the New York Tribune.

He described the work of the Impressionists as “decidedly interesting” and provided a comprehensive description of the aims of the Impressionist movement:

“the painter’s proper field is the actual, and to give a vivid impression of how a thing happens to look, at a particular moment, is the essence of his vision.”

However, he showed that he had not quite grasped the essence of the Impressionists when he compared them to the English Pre-Raphaelites. Despite the confusion, this review was instrumental in introducing American audiences to the emerging movement.

Albert Wolff

The review that undoubtedly stands out the most from the Second Impressionist Exhibition, however, is the one penned by Albert Wolff in Figaro. Wolff attacked the Impressionists with a shocking level of vehemence, describing the artists as “lunatics” and stating that,

“Some people are content to laugh at such things. But it makes me sick at heart”.

His review was so extreme that it prompted Eugène Manet to challenge Wolff to a duel for questioning the morality of his wife, Berthe Morisot.

Morisot herself was not overly phased by the comments and saw them as a natural resistance against the work of the Impressionists. Like Monet, she viewed such criticism as something critics did and did not take his words personally.

Nonetheless, she did write some preemptive letters to her aunts to notify them that they might read about her in the Parisian newspapers. In the writing of other critics, her work had largely been praised with many, somewhat predictably, emphasising the ‘femininity’ of her paintings.

5. The Aftermath

Following the exhibition and the onslaught from the critics, some artists fared better than others.

Despite continued resistance to their work, 1876 proved to be a productive year for the Impressionists as a whole.

Sisley, Monet and Pissarro

Heavy flooding in Marly saw Sisley embark on his series of landscapes that captured the underwater world the region had become and these paintings would be some of the highest regarded works of his career.

Similarly, Monet set upon a new series of works in which he found a novel direction among the smoke and the trains in the railway station of St. Lazare in Paris.

Meanwhile, Pissarro became very depressed and Cézanne, worried about his friend, invited him to go and stay with him in L’Estaque where he was working on a commission for Chocquet. He encouraged Pissarro to try painting the sea in order to find a new direction for his work and provide him with some much needed inspiration.

Money worries

Though some sales had been made at during the Second Impressionist Exhibition, many Impressionist artists continue to work in a precarious financial situation, reliant on the generosity of dealers and collectors and the occasional commission.

Though it was widely assumed that Monet was becoming extremely wealthy from the sale of his paintings, he was also finding that he lacked the funds to live the bourgeois lifestyle he wanted in his home in Argenteuil.

His growing reputation caused his creditors to pursue him even more tirelessly than before!

Manet

Whilst Manet had decided not to include his work in the Second Impressionist Exhibition, he did not benefit from distancing himself from the Impressionists. His work continued to be rejected from the Salon, even while the work of one of his pupils, Eva Gonzales, was accepted.

Morisot insisted in letters that he was

“perfectly good-humoured about his failure”.

But there was also evidence that he was growing more desperate.

Later, Manet attempted to ingratiate himself with Wolff in a move to get closer to the decision makers at the Salon. He began painting his portrait but Wolff soon grew tired of sitting for him and the work was abandoned.

The Third Exhibition

The Third Impressionist Exhibition would open the following year, in 1877, thanks once again to the generosity of Caillebotte. After the modest financial success of the Second Impressionist Exhibition, the Impressionists reserved the space in Durand-Ruel’s gallery once more. This exhibition would see Cézanne return to the group and be marked by many more rivalries and disputes as the pressures on the group mounted.