1. Preparing for the exhibition

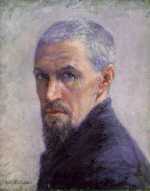

Gustave Caillebotte was adamant that the Impressionists should hold a Third Impressionist Exhibition.

As with the Second Impressionist Exhibition, Caillebotte put forward the majority of funds for the exhibition. He was resolute in his aims to see the Impressionist movement continue and succeed and he poured his energy and money into staging another exhibition.

Quarrels

The artists quarrelled over how the Third Impressionist Exhibition should proceed.

Claude Monet and Edgar Degas disagreed over whether or not to encourage new artists to join the group. Degas felt that new blood was needed to drive the work of the Impressionists forward but Monet staunchly disagreed, fearing that unknown artists would dilute the impact of the group. Meanwhile, Camille Pissarro was keen to make the movement more political and he advocated for the group to align themselves with socialist causes.

Similarly, the rivalry between Caillebotte and Degas for control over the organisation of the exhibition had continued since the Second Impressionist Exhibition. According to some accounts, they argued frequently, but it also appears as though Caillebotte was largely a peacekeeping figure in the group. According to sources, he had the calm temperament needed to diffuse disputes among the other artists and enable the group to work together.

The Venue

The previous Impressionist exhibition had been held in a gallery owned by Paul Durand-Ruel but there was yet more debate on whether it should be held in the space for a second time. It was discovered that the gallery space had been rented out for the full year, halting the group’s plans.

Degas pushed for a new space that would feel fresh and different. Initial talks included plans to hold the exhibition in a barrack built on the vacant lot where the Paris opera house used to stand. Pragmatic as usual, Caillebotte was the one who found appropriate premises for the exhibition, located on the the same street as Durand-Ruel’s gallery and owned by one of his friends.

The exhibition space at number 6 Rue Le Peletier was grand and spacious, spread across five large rooms on the first floor of the building.

The space was well-lit, giving the Impressionists the opportunity to showcase their work in the best fashion and lending legitimacy to their exhibition. It was further agreed that there should be no limit on the number of paintings each artist was allowed to show to fill the gallery with their best work.

The Salon

One new restriction that was introduced, on the insistence of Degas, was that the artists should cease to submit works to the Salon.

Degas believed that the group represented the survival of modern art and he felt very strongly that there was a conflict between the Salon and the ‘Exposition des Impressionistes’. This was in stark contrast to his earlier insistences in 1874, which had seen him actively attempt to recruit Salon artists to exhibit with the Impressionists in order to lend the group greater legitimacy.

Nevertheless, the others agreed to his stipulation, though Paul Cézanne was exempted from the rule.

2. The Artists

Fewer artists contributed their paintings to the Third Impressionist Exhibition than there had been in previous years.

Several lesser known Impressionist artists dropped out, including Édouard Béliard (1835-1912) and Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic (1839-1889).

In total, there were 18 painters in the exhibition with more than 230 works contributed.

Berthe Morisot

Renoir, Degas and Caillebotte all contacted Berthe Morisot to ask her to exhibit with them again.

She accepted gladly, despite the controversy caused among her family for the negative reviews of the previous exhibition. Morisot contributed a number of oil paintings and a large wall in the central gallery was dedicated entirely to her paintings, giving her the position of honour.

Arguably the most notable of Morisot’s paintings on display at this particular exhibition was ‘La Psyché’ or ‘The Psyche Mirror’ from 1876. The painting depicts a woman looking into a mirror - known as a Psyche at this time - and gathering up the fabric of her clothing as she stands at an angle. Rich light enters into the windows and the painting is almost entirely made up of a range of delicate tonal whites.

Morisot’s figure is shown in thoughtful solitude, a common feature in many of her paintings where she sought to depict the private moments of women in the home. This painting received much positive attention in the press.

Newcomers

As well as Caillebotte, Morisot, Monet, Pissarro, Degas, Auguste Renoir and Alfred Sisley, there were also some newcomers. Among them were Pierre Franc-Lamy and Frédéric Samuel Cordey, both acquaintances of Renoir.

They attended his studio almost every afternoon, using him as a mentor after leaving the Ecole des Beaux Arts due to their frustration with their teachers. Following Renoir’s example, both artists adopted the Impressionist style in their work.

Cezanne

Most importantly, this exhibition saw the return of Cézanne. He showed three watercolours, two of which were named ‘Impression d’après nature’, and a number of oil paintings. These were arranged in the central room, on the long wall opposite Morisot’s work.

In his oil paintings, he largely chose still lifes and landscapes but ‘Bathers’ from 1875-76 was one exception. Nude bathing scenes were a subject that came up time and time again in Cézanne’s work. He was fascinated by the human figure but rarely painted nude models, instead drawing the women from his imagination or classical and Renaissance art. Variations of these nude bathers continue even into his later work, appearing in different classical poses.

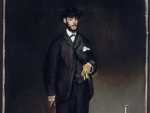

Degas similarly contributed paintings of nude women, but his figures were drawn from the brothels, clubs and dance halls of Paris rather than from classical art. His work was given a gallery all of its own in the farthest room in the exhibition space. He further exhibited pastels and lithographs and a portrait of his friend Henri Rouart.

Monet's Gare St Lazare

One of the standout series displayed was that of Monet’s views of Gare St. Lazare, showing the station shrouded in a fog of smoke from the steam trains. He had conceived the idea for the series when staying in a rented apartment in the rue Moncey, close to the station. In order to realise his vision, he dressed in his finery and marched into the office of the director of the station. Not wanting to appear ignorant, the director agreed to his demands, assuming he was a famous and fabulously wealthy painter.

Thanks to his gumption, Monet had been given the entire station to paint from, with the platforms cleared of people, the trains delayed and extra coal added to the fires to create as much smoke and steam as he needed for the effect. The results were an astonishing success and all the Impressionists benefitted from Monet’s stroke of inspiration.

Durand-Ruel agreed to buy the whole series and he also paid every Impressionist artist a small sum to help keep them afloat.

Hanging the paintings

All the artworks in the Third Impressionist Exhibition were curated and hung by a joint team of Monet, Renoir, Pissarro and Caillebotte. Though some artists’ paintings were hung together, this was not as rigidly upheld as the previous Impressionist exhibition.

Instead, it was decided that the first room should feature a selection of works by Monet, Caillebotte and Renoir, and their larger works were shown in other rooms.

3. Supporters of the Third Impressionist Exhibition

As well as the artists’ contributions, many key supporters of the Impressionists also aided in contributing paintings to the exhibition.

This year, as in 1876, Victor Chocquet formed one of the most important shows of support for the Impressionists.

He continued to commission work from many of the artists in the group and contributed a number of pieces from his collection to the Third Impressionist Exhibition.

Choquet the Ambassador

On top of his contributions as a collector, Chocquet also became heavily involved as a self-appointed ambassador. Since retiring, he used his time visiting the exhibition to grapple with visitors over topics surrounding the art of the Impressionists. He challenged any incredulous viewer to a battle or wordplay and debate, tirelessly championing the work of all the Impressionists and Cézanne in particular.

Georges Rivière, a friend of Renoir, described how Chocquet

“challenged the laughers, made them ashamed of their jokes, [and] lashed them with ironical remarks”.

He was,

“persuasive, vehement, domineering in turn […] the most charming and formidable of opponents.”

Reports of Chocquet’s enthusiastic cheerleading even tell of visitors who deliberately incited Chocquet into a debate just to see him launch into a long message of support and admiration.

The Charpentiers

Georges Charpentier and his wife, Marguerite Charpentier, were another source of support for the Impressionists and they contributed paintings to the Third Impressionist Exhibition, along with Georges de Bellio, a Romanian physician close to the group.

L'Impressioniste

At Renoir’s suggestion, Rivière began the publication of a weekly journal titled ‘L’Impressioniste’ in order to help publicise the exhibition.

He heavily praised the works on display, using prose thick with exaggeration and adoration. Renoir also contributed a small number of articles to the publication, largely focussed on the topics of architecture and decorative art.

In his articles, Rivière was particularly praising of Cézanne’s work, which received some of the worst criticisms of all the artists. Though the publication was a valiant effort intended to garner public support, the few issues sold were not enough even to cover running costs. As a result, Rivière was forced to shut down his bold venture after just four weeks.

4. The reactions of the public

The Third Impressionist Exhibition received the most positive reception from the public of the three exhibitions.

There was a comparatively large attendance and the crowd seemed to be less jeering than in previous years, which was met with relief by the artists. Nonetheless, the press continued to attack the group and there were the usual tales of outrage and disgust.

Disturbing the upper classes

Perhaps one of the best anecdotes comes from Rivière who describes a wealthy banker standing in front of Renoir’s ‘Le Bal au Moulin’ (1876) for some moments. He stood, silently frowning, and then promptly marched back to the entrance and demanded he have his money back. Similar reactions were also witnessed repeated by other visitors.

Indeed, it was generally the upper class visitors who found the work most disturbing. They could not understand why the working-classes at their leisure were deemed a suitable subject for high art. The general consensus was that the artists were dangerous revolutionaries.

Monet’s series of paintings depicting steam trains billowing black smoke and soot were met with particular horror. No one had ever depicted the industrialised world in such a way.

By contrast, Caillebotte’s work, including ‘Street in Paris’, ‘A Rainy Day’ and ‘Le Pont de l’Europe’ were relatively conventional. Nevertheless, his pale palette and the use of high contrast in his paintings still stirred indignation.

Cartoons

Cartoons published in la Charivari depict the caricatured reactions of the public to the exhibition. One shows a policeman with his arms up, blocking the way of a well-dressed pregnant woman saying

“Lady, it would be unwise to enter!”

The second depicts a man in a top hat, staring at a painting and exclaiming,

“But these are the colours of a corpse!” to which the painter replies, “Indeed, but unfortunately I can’t get the smell.”

This was undoubtedly a reference to a comment made by Albert Wolff in 1876, in response to nudes by Renoir.

5. In the press

Of all the Impressionist exhibitions thus far, the Third Impressionist Exhibition won the most praise in the press.

Whilst the response was still lukewarm, and in some instances extremely hostile, the Impressionists were given more space in newspapers and journals. Some reviews even began to entertain the idea that their work had value.

Review in L'Artiste

Arsène Houssaye was one such critic. He approached Rivière to ask for notes on the paintings in the exhibition and these were published in the L’Artiste in November, titled ‘Les Intransigents et les impressionists: Souvenirs du salon libra de 1877’. This article represented a significant win for the Impressionists as it demonstrated that there was at least some attempt to take their work seriously.

However, Houssaye requested that Rivière not include Pissarro or Cézanne in his writing. Consequently, only Degas, Monet, Sisley, Morisot and Caillebotte received recognition. This incident demonstrated the general consensus that Pissarro and Cézanne were too offensive for the tastes of upper class readers and thus were best ignored.

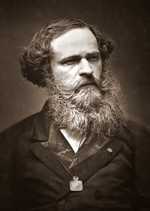

Emile Zola

As well as Houssaye’s interest in the Third Impressionist Exhibition, Émile Zola also wrote a lengthy review that was far more positive than his assessment of the Second Impressionist Exhibition. He mentioned Monet’s talent and placed him at the head of the group, but he was also highly supportive of Cézanne.

Going against popular opinion, Zola described Cézanne as,

“certainly the greatest colourist of the group.”

He went on to describe his landscapes of Provence as having,

“a splendid character. The canvases of this painter, so strong and so deeply felt, may cause the bourgeois to smile, but nevertheless contain the makings of a great artist.”

Zola was also quick to point out that, “the public, though laughing, throngs to their exhibition. One counts more than 500 visitors a day. That is success”.

Even the critic Théodore Duret, previously implacably opposed to the movement, delivered a back-handed compiment:

“the majority of the visitors were of the opinion that the exhibiting artists were perhaps not devoid of talent and that they might have executed good pictures if they had been willing to paint like the rest of the world”.

6. The Aftermath

At the end of the show, on the last day of April, some of the artists agreed to hold an auction of the works.

Morisot and Monet declined but Pissarro and Caillebotte joined with the others.

Though he had no financial incentive, Caillebotte wished to stand by the artists by putting his works up for sale. Unfortunately, the auction did not achieve their aims and many of the artworks sold at disappointingly low prices.

In this respect, the second Impressionist auction was about as successful as the first.

La Cigale

A few months after the show finished, Degas’ friend Ludovic Halévy, an author and playwright, released a satirical play titled ‘La Cigale’. It opened at the Théâtre des Variétés in Paris and featured an Impressionist painter as the central character.

Halévy had made a visit to the offices of ‘L’Impressioniste’ during the exhibition and made enquiries to Rivière, as well as buying copies of the paper. The play featured numerous jokes on art and Impressionism, showing Halévy’s research into the topic. The comedy was met with laughter from the crowd. Apparently, Renoir and Rivière seated in the audience laughed too.

A partial success

The Third Impressionist Exhibition was regarded as a partial success. The artists still looked to be a long way from receiving the recognition and admiration they desired but there was also evidence that, at least to some extent, they were beginning to be considered as more than just a source of amusement.

The large crowds were encouraging for the artists, despite the jeers, and provided a crucial source of monetary support for the exhibition. However, the Impressionists would have to wait longer before many of them felt financially secure and truly successful.