1. Why was the first exhibition held?

By 1874 the group of artists that would become known as the impressionists had been trying to achieve recognition by submitting their works to the annual Salon (exhibition) held by the Academy des Beaux-Arts for over a decade.

More often than not, the jury which selected the paintings to be shown rejected the impressionists’ work. And, when their works were accepted, they were usually lambasted by acidic art critics.

The problem was that the art establishment expected artists to paint in a particular way: they wanted find, blended brushstrokes; largely dull colours; and religious, historical or mythological scenes. This was the polar opposite of the impressionist technique, which used broad, unblended brushstrokes; bright colours; and scenes of modern life.

Here are a few examples of the shocking comments made by art critics between 1864 and 1873:

- “never has a painting received more laughter, mockery and catcalls” (of Manet’s Olympia).

- “painted with a pistol” (of Cezanne’s portrait of Antony Velabregue).

Edouard Manet, whilst supportive of the independent impressionist exhibitions, decided not to submit. He still had ambitions of persuading the Salon jury and the art establishment of the value of his work.

Manet’s view was fortified by the fact that, in 1873, he had scored a rare Salon success with a picture of a man drinking a pint of beer called the Bon Bock (the Happy Beer).

Manet tried to persuade Monet against the idea of an independent exhibition, saying:

“Why don’t you stay with me? Can’t you see I’m on a winning streak?’

“I will never exhibit in the shack next door [to the Salon]. I enter the Salon through the main door, and fight alongside the others.”

But Monet would not be persuaded. Both he and Degas (who needed money because his family business had recently failed) both saw the exhibition as an opportunity to show their works to a wider audience and to drum-up some lucrative sales.

2. Organisation

The main organisers of the first exhibition were Monet, Pissarro, Degas and Renoir.

The venue

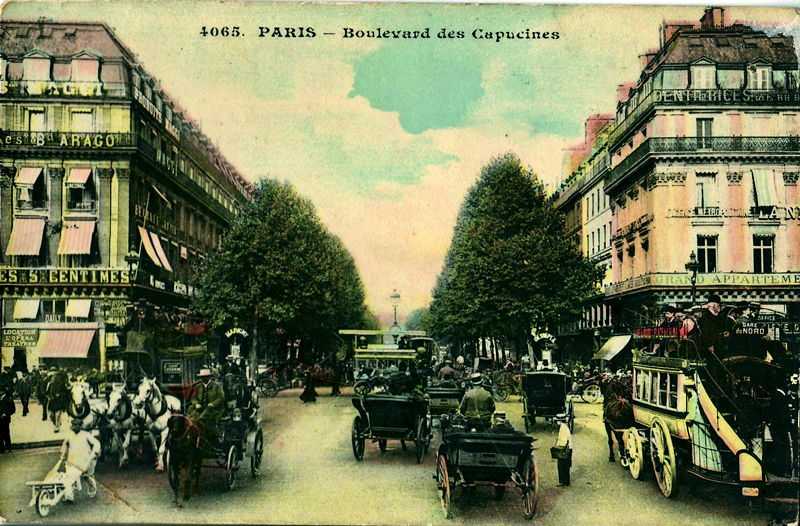

Monet happened to know the caricaturist and photographer known simply as Nadar, who was vacating his studio on the Boulevard des Capucines.

This was a perfect venue. The Capucines, one of the four ‘grand boulevards’ of Paris, having been constructed during Baron Haussmann’s remodelling of Paris. Finished in 1865, it was 35-metres wide, tree-lined and presented a prime commercial site. Nadar’s third floor studio was also large and bright, having floor to ceiling windows.

The Anonymous Society

After the idea of an independent exhibition was mooted in 1873, Monet and Pissarro decided that they should incorporate a joint stock company in which artists and their supporters would hold shares.

This slowed things down. Monet and Pissarro spent months drafting the charter (the rules governing how the company should operate), using a charter from a baker’s co-operative as a guide.

This was complicated because it was clear to Monet that the company should have no political goals. The impressionists were already distrusted by the establishment, and, given that Paris was just starting to recover from a communist rebellion (called the Paris Commune), Monet wanted to take no chances.

Once the charter was finalised on 27 December 1873, Monet and Pissarro had to get people to subscribe for the company’s shares (at a cost of 60 francs a year, paid at the rate of 5 francs a month). Degas played a key role in lobbying for signatures.

The company ended up being called the not-so-catchy:

- (French) Societe Anonyme a capital variable Des Artistes, Peintres, Sculpters, Graveurs et Lithographers

- **(English)**The Joint Stock Company of Artists, Painters, Sculptors, Engravers and Lithographers

Discord

The organising committee consisted of Monet, Degas, Pissarro, Renoir, Sisley and Berthe Morisot.

One of their first tasks was to decide whether to let Cezanne participate. The problem was two-fold: Cezanne had been singled out for particular criticism in previous years; and he planned to submit a peculiar work called A Modern Olympia.

Of the committee, only the broad-minded Pissarro was in favour of Cezanne’s inclusion. When Manet was consulted, he remarked:

“What, get myself mixed up with that buffoon? Not likely!”

On the other hand, Degas was pushing for the inclusion of fashionable painters such as Boudin, Bracquemond and Meissonier, so as to give the first exhibition credibility. This settled the matter: the committee decided that if outsiders were to be considered there was no way that they could exclude one of their own.

The next thing to do was to arrange the paintings. This was another potential source of controversy, given the way that the Salon jury decided where paintings were to be hung (placing pictures that they disapproved of near the ceiling, known as skying). Renoir oversaw a process of classifying paintings according to their size and then drawing lots.

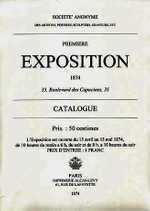

The catalogue, dates and tickets

Renoir’s brother Edmond, a budding journalist, was in charge of the catalogue. Priced at 50 centimes, it proudly announced the ‘Premiere Exposition’. Opening times would be 10am to 6pm and then 8pm to 10pm (to encourage as many to come as possible).

Tickets were 1 franc (the same price as Salon tickets).

In total about 3,500 came. This broke down into about 200 attendees on the opening day and about 100 per day thereafter.

The exhibition ran from 15 April 1874 (two weeks before the start of the Salon) until 15 May 1874.

3. Paintings on display

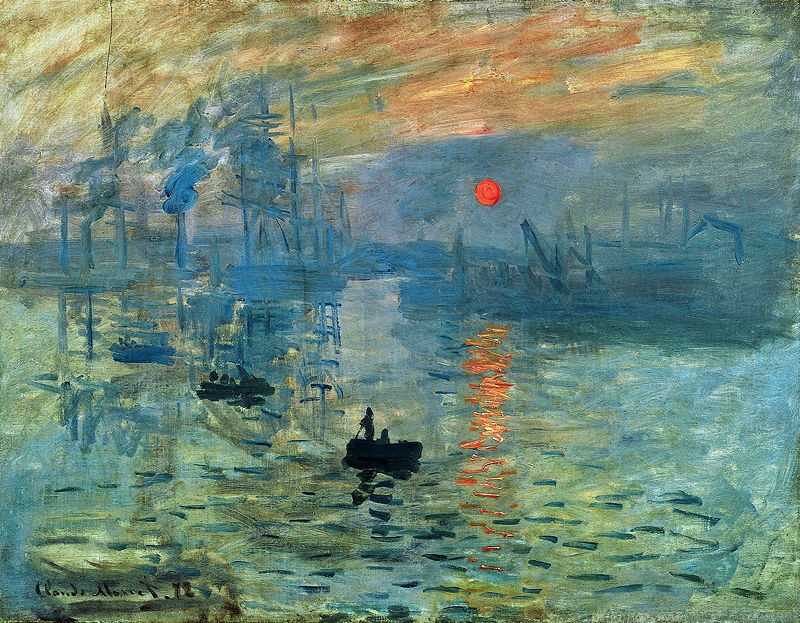

The most famous painting to be displayed was Claude Monet’s Impression Sunrise.

This work, of a rowing boat and setting sun at Le Havre, is one of our top 10 impressionist paintings. It ticks all the impressionist boxes: short unblended brushstrokes; a bright setting sun; and a thoroughly modern scene.

As for the other impressionists:

- Degas submitted 10 works in total, including Dance Class, Laundress, After the Bath and Carriage at the Races.

- Monet submitted nine works. Aside from Impression Sunrise, his most notable entry was Boulevard des Capucines.

- Pissarro showed five works (including Hoar-Frost and Chestnut Trees at Osny);

- Renoir seven works (including the Theatre Box and Dancer);

- Cezanne three (including Modern Olympia and a view of Auvers-sur-Oise entitled The House of the Hanged Man);

- Sisley five landscapes; and

- Berthe Morisot nine works (including The Cradle and Hide-and-Seek).

The full list of other artists whose work was on display is as follows (in alphabetical order): Attendu, Beliard, Boudin, Bracquemond, Brandon, Bureau, Cals, Colin, Debras, Latouche, Lepic, Lepine, Levert, Meyer, de Molins, Mulot-Durivage, de Nittis, A. Ottin, L. Ottin, Robert, and Rouart.

Sales were not good. Sisley was the most successful of the group, earning 1000 francs. Monet and Renoir made just under 200 francs each; Pissarro earned 130 francs; and Degas and Berthe Morisot sold nothing whatsoever.

4. Hostile reviews

The reviews were overwhelmingly negative.

Generally

The most famous review of the exhibition was penned by an acidic journalist called Louis Leroy. Entitled ‘Exhibition of the Impressionists’, he wrote:

“Impression! Of course. There must be an impression somewhere in it. What freedom … what flexibility of style! Wallpaper in its early stages is much more finished than that.”

Ironically, it was reviews such as this that popularised the term impressionism.

Another critic said that the exhibition was a big practical joke, put on by a comedian who amused himself by:

“dipping his brushes into paint, smearing it onto yards of canvas, and signing it with different names”.

Another critic wrote the following entry for the ‘Exhibition News’ column of La Patrie:

“There is an exhibition of the INTRANSIGENTS in the Boulevard des Capucines, or rather, you might say, of the LUNATICS, of which I have already given you a report. If you would like to be amused, and have a moment to spare, don’t miss it.”

Finally, one of the best-known Salon reviewers opined that:

“M. Manet is among those who maintain that in painting one can and sought to be satisfied with the impression. We have seen an exhibition by these impressionalists on the boulevard des Capucines, at Nadar’s. M. Monet – a more uncompromising Manet – Pissarro, Mlle Morisot, etc, appear to have declared war on beauty.”

Cezanne

Paul Cezanne was singled out for particular criticism. He had insisted on submitted a work called A Modern Olympia. To be honest, this is a weird work—the figures remind me of children’s toys that have been put into the microwave.

But the critics were even harsher. One described Cezanne as a:

“sort of madman, painting in a state of delirium tremens”.

5. What happened next?

Though the exhibition was a bust commercially, Monet managed to sell Impression Sunrise and four other paintings to department store owner Ernest Hoschede for a total of 4,800 francs.

But things for the rest of the group were soon to go from bad to worse as Paul Durand-Ruel suspended the payments on instalment that he was making to the group.

How did Manet fare?

Manet’s focus on the Salon also backfired. Of the three works he submitted to the 1874 exhibition, two were summarily rejected. The third, a heart-warming depiction of a mother and daughter at a railway station entitled The Railroad, was lambasted by critics (eg, the figures were “both cut out of sheet-tin”).

Ironically, given his refusal to get involved, many reviewers placed the blame for the first exhibition on Edouard Manet. A rude review in La Presse described the group as ‘disciples of Monsieur Manet’; and a caricature in Les Contemporains showed Manet wearing a crown under the title ‘Manet, King of the Impressionists’.

Liquidation of the company

In December 1874, Renoir chaired a meeting of the company’s shareholders. It had liabilities of 3,713 francs and cash in hand of a mere 278 francs. Each exhibitor owed 184 francs 50 centimes. The group made the unanimous decision to liquidate the company.

An auction and seven more exhibitions

The Impressionists, however, were not ones to give up. They organised an auction at the Hotel Drouot in 1875 and, when that did not go as planned, held a second exhibition in 1876 and six more exhibitions in the years 1879 to 1886.