1. 1840-1865: Monet's early years

Monet was born into a humble Parisian household on 18 November 1840, the second son of a shopkeeper.

Monet's childhood

When he was six, Monet's parents decided to move to Le Havre so that his father could join his brother-in-law’s chandler's business. The move suited Monet: he loved roaming the beaches and cliffs, often playing truant from school.

He also had an early talent for art, or rather caricature. Starting with sketches of school friends and teachers, he was soon poking fun at local celebrities and selling his works for between 10 and 20 francs a go at the local picture framer's shop. Our first picture is of one of his caricatures, always signed Oscar (Claude-Oscar was Monet's first name).

Boudin

It was at the picture framer's that Monet met Eugene Boudin, a landscapist who painted en plein air (outdoors). This was a recent phenomenon, made possible by paint becoming available in metal tubes. It was also looked down on by the art establishment, who thought that sketchess hould be made outside and paintings produced in studios.

Boudin took the young Monet under his wing and showed him how to paint. Monet was later to say:

“if I became a painter, it was thanks to Boudin. He was a man of infinite kindness and took it upon himself to teach me.”

Although Monet’s father disapproved, he did not stand in the way when his maternal aunt produced a letter of introduction to one of her painter contacts in Paris. This soon led to Monet turning up at Suisse’s painting studio in 1859, where he met Camille Pissarro (1830-1903).

Paris, the army, back to Le Havre and Jongkind

In 1860, Monet was conscripted into the army. He opted to serve in Algeria but promptly caught typhoid fever. He came back to Le Havre to recuperate and his family bought him out of the army.

It was at this stage that Monet met Johan Jongkind, a Dutch landscapist. Jongkind taught Monet how to appreciate light, with Monet later describing him as his “true master” and the person who

“completed the education of my eye”.

But Jongkind was a notorious drunk and womaniser and Monet’s family did not approve of his new friend. This was the main reason why they were happy for him to go back to Paris on condition that he sought to obtain entry to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts (the respectable but highly conservative fine arts school). They even provided a small allowance.

Gleyre's studio

Monet ended up in the studio of Charles Gleyre, an idealist painter who was happy to let students develop their own styles. It was here that he met Auguste Renoir, Frederic Bazille and Alfred Sisley.

He also encountered Paul Cezanne, regarded by other students as an oddball.

Monet was a cocky student. Good looking, witty and confident in his abilities, he was popular with the ladies. He once rebuffed an unwanted advance by saying:

“I’m sorry, but I only sleep with duchesses or maids. Anything in between I find revolting. My ideal woman would be a Duchess’ maid!”

On another occasion, Gleyre returned to find Monet on the model’s podium, rearranging the position of the nude female posing for the class.

2. 1865-70: Early successes and failures

Monet was 25 in 1865. The next five years were mixed: he had success and failure with his work; he had a son; and he had major money worries.

Initial Salon success

The 1865 Salon* was overshadowed by Manet’s infamous Olympia. This canvas of a nude prostitute, staring brazenly at the viewer, was found shocking by the establishment, critics and the public alike. It is surprising that it was accepted by the jury in the first place.

But 1865 also marked Monet’s Salon debut, with two landscape works: the Mouth of the Seine at Hornfleur (pictured) and The Bridge at Heve at low tide. They achieved some positive commentary, much to Manet’s fury: he thought the younger Monet was trading off his name!

* The Salon was the exhibition held by the French Academy des Beaux Arts in Paris. The Salon was the main place at which new painters could showcase their work, and thereby obtain commissions or positive reviews. It was attended by hundreds of thousands of people in the spring of each year it was held (either annually or bi-annually). But the Academy was very conservative: it liked history, mythology and religion; and it hated modern works, especially those with a light palette and which used broad brush-strokes. The works that would be displayed at the Salon each year were voted on by a jury.

Woman in the Green Dress

Worse was to come for Manet: Monet’s 1866 entry was a huge hit. Entitled Camille or The Woman in the Green Dress, the painting shows the green and black train of a silk dress. Emile Zola, who was to become one of the impressionists’ biggest supporters, said that the dress was

“both supple and firm. Softly it drags, it is alive, it tells us quite clearly something about the woman”.

The critic of La Lune (The Moon) said:

“Monet or Manet? Monet. But we have Manet to thank for Monet. Bravo, Monet. Thank you, Manet.”

This probably irked Manet. But it was a compliment. He had given the other impressionists the confidence to paint in their own way and not conform with what the conservative Academy des Beaux-Arts expected.

And failures ...

Monet’s 1867 Salon entry was, by contrast, a complete flop. Entitled Women in the Garden, this scene of four women was probably rightly rejected by the jury.

Interesting fact...

Women in the Garden was painted on a huge 2 x 2.5 metre canvass, so was sure to get noticed. But one of the women looks like a hovering ghost and two of the others have a distinctly masculine air. Posterity has also judged it a curious work.

In the aftermath of this rejection, Monet first floated the idea that the impressionists should hold their own independent exhibition; but the proposal is taken no further because of a lack of finance.

In 1869 (there was no Salon in 1868), both of Monet’s entries—the Magpie and a seascape—were rejected. So too were his entries for 1870.

Money problems

These rejections came at a tumultuous time in Monet’s personal life. Monet had had money worries since 1864. But things came to a head in 1867 when his girlfriend and later wife, Camille Doncieux, fell pregnant.

Strange but true ...

Monet’s father cut his son's allowance after learning that Camille was pregnant. Monet pretended that he had broken things off with Camille to get the allowance reinstated. This led to the absurd situation of Monet holidaying with his parents and Aunt in Normandy in 1868, leaving Camille in Paris under the supervision of Renoir and a medical student. Camille gave birth while Monet was away.

Frederic Bazille helped by buying the rejected Women in the Garden for the (absurdly high) price of 2,500 francs, doled out in instalments of 50 francs a month. But that was insufficient to pay for painting materials and feed and clothe Monet and his young family.

Attempted suicide

Things go so bad that, in the summer of 1868, Monet made a rather half-hearted suicide attempt by throwing himself into the Seine. He was too good a swimmer to let himself drown, and he soon regained his senses. But the fact of his attempt shows how bad things were.

3. 1870-76: War, London and the early impressionist exhibitions

The early 1870s was an interesting time for Monet: he fled Paris for London to avoid the Prussian war; he met Durand-Ruel, who was to become the main impressionist dealer; and he took part in the first two impressionist exhibitions.

War and London

Napoleon III’s disastrous foreign policy came to a head in 1870 when he declared war on the Prussians. The French army was soon defeated and it became clear that Paris would be surrounded. Some — Manet and Berthe Morisot included—stayed. But Monet fled to London.

This turned out to be a real stroke of luck. Monet met art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel in London, who had an interest in a gallery on Bond Street. Durand-Ruel had previously been a dealer and advocate for the Barbizon School, but he was quick to see the potential of the impressionists.

Monet also took the opportunity to study the works of the English painters John Constable and J.M.W. Turner.

The first impressionist exhibition

The first impressionist exhibition was held in 1874 at the studio of the photographer known as Nadar on the Rue du Capucines. The lead-up to the exhibition saw wrangling amongst the artists about the articles of association for a company formed for the occasion called the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors and Engravers etc.

Once the company was incorporated the exhibition came together. Thirty painters exhibited 165 works in all. The leading contributors were Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Degas and Berthe Morisot (Manet helped behind the scenes but refused to exhibit, focussing on the Salon).

Degas, Renoir and Monet were the main organisers. Entrance was one franc and the exhibition ran for a month from 15 April.

Around 3,500 people came, around 100 a day. But the reviews were horrific. Monet’s Impression Sunrise was singled out for particular censure by the acidic critic Albert Woolf:

“Impression! Of course. There must be an impression somewhere in it. What freedom ... what flexibility of style. Wallpaper in early stages is more finished than that.”

Only Paul Cezanne’s canvasses attracted worse reviews. The day before the exhibition closed there was an ironic entry in the exhibition news column of La Patrie:

“There is an exhibition of the intransigents in the Boulevard des Capucines, or rather, you might say, of the lunatics, of which I have already given you a report. If you would like to be amused, and have a moment to spare, don’t miss it.”

At the end of the year, Renoir chaired a meeting of the Society. With cash of 278 francs and liabilities of almost 4000 francs, each exhibitor owed 278 francs!

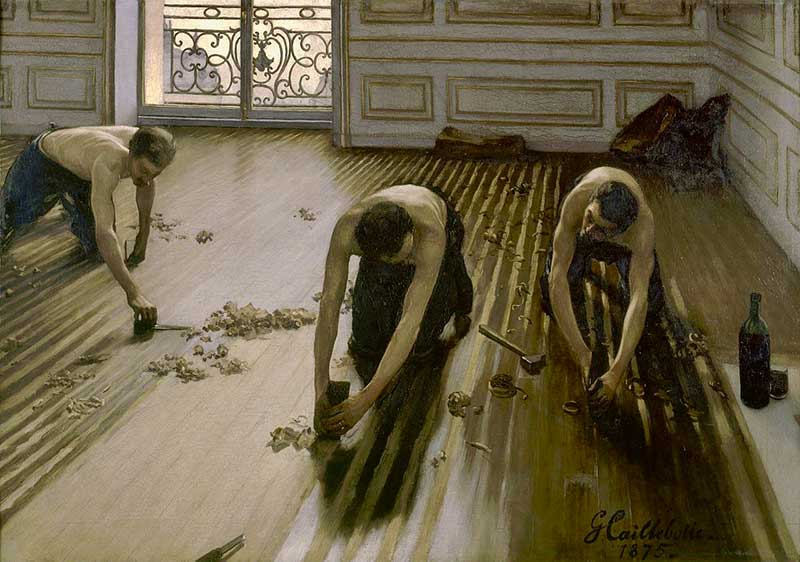

The second exhibition

The second impressionist exhibition, held two years later, did little to improve matters. Durand-Ruel lent the group his gallery on the Rue Le Pelletier.

Gustave Caillebotte largely funded the exhibition and took over much of the organisation (much to Degas’ irritation). Manet again refused to be involved. And Caillebotte’s The Floor Planers stole the show.

Monet has some success too. His colourful Japanese Girls old for 2,000 francs. And the press was not all bad. Henry James wrote a positive article in the New York Tribune. But Woolf again was implacably opposed to the movement. He wrote:

“The Rue de Pelletier is certainly having its troubles. After the fire at the Opera, a new disaster has befallen the district. An exhibition of so-called painting has opened at Durand-Ruel’s. ... Here, five or six lunatics deranged by ambition ... have put together an exhibition of their work. ... They take canvas, paint and brushes, splash on a few daubs of colour here and there at random, then sign the result. The inmates of the Ville-Evrard asylum behave in much the same way.”

At least the show turned a (very small) profit!

4. 1876-1883: problems, tragedy and hope

The late 1870s and early 1880s were difficult for Monet: he had money worries almost continually and lost his first wife, Camille, when she was aged just 32.

Money problems ...

Monet’s father had died in 1871 and he sold a number of paintings at the start of the decade for good prices.

But Monet was a spendthrift. The rented house that Manet found for him in Argenteuil following his return from London did not come cheap. And Monet engaged household staff, gardeners and bought the latest luxuries (an expensive tea set, bag and linen can be seen in The Luncheon (1873)).

Realising that he had to economise, Monet moved first to a smaller rented house in Argenteuil and then to a modest home in Vetheuil in 1878.

Begging letters

This period is characterised by Monet sending letters to Paul Durand-Ruel, Caillebotte, Manet and others begging for handouts. Sometimes he asked for as little as 20 francs.

A typical letter, sent to Manet in 1876, is as follows:

“Things are going worse and worse. Since the day before yesterday, I have not had a penny, and no credit anywhere — not at the butcher’s or baker’s. Could you possibly send me 20 francs by return? It would tide me over for the moment.”

One problem was that Durand-Ruel couldn’t shift the stock that he had bought earlier in the decade. And the horrible reviews of the impressionist exhibitions didn’t help. Durand-Ruel had no option but to suspend the instalment payments he was making for those works.

Camille Doncieux

Monet had met Camille Doncieux in the mid-1860s, with her modelling in Woman in the Green Dress. The two quickly formed a relationship, with Camille giving birth to Monet’s first son, Jean, in 1867. A second son, Michel, followed 11 years later.

But by 1879 Camille was seriously ill, perhaps as a result of a botched abortion. Monet’s money woes prevented him from being able to pay for the best medical care, and Camille died in September 1879, aged just 32.

Strange but true...

One of Monet’s most remarkable works is Camille Monet on her Deathbed (pictured). Monet painted his dead wife as the first rays of sunlight were entering her bedroom the next day. Monet described his behaviour as follows:

“... my gaze fixed upon her tragic temples and I caught myself observing the shades and nuances of colour death brought to her countenance. Blues, yellows, greys. The wish came upon me to record the image of her who was departing from us forever. ... my reflexes took possession of me in an unconscious process.”

Glimmers of hope

Though the late 1870s are early 1880s were tough times, there were glimmers of hope.

First, Monet’s Gare Saint Lazare series, produced in 1877, was recognised by the hard-up Durand-Ruel as being quite breath-taking work. He therefore made an exception to his policy of buying no further impressionist works until the market picked up. And he doled our small sums to the rest of the impressionist group.

Dinner party conversation ...

The story of how Monet blagged his way into the Gare Saint Lazare, by pretending that he was a famous artist (this would take another decade), is worth knowing.

Second, Monet seemed to shake the malaise that had overtaken him when Camille died in 1882. He visited Normandy a number of times, and painted a number of coastal works including The Fisherman’s House and The Custom’s House, both at Varengeville, and Walk on the Cliff at Pourville.

Third, the market for impressionist works improved in the early 1880s. Monet’s solo show at Durand-Ruel’s gallery in 1883 produced good reviews. And the dealer started to conquer the American market in the middle of the decade.

5. 1883-1926: Giverny and Water Lilies

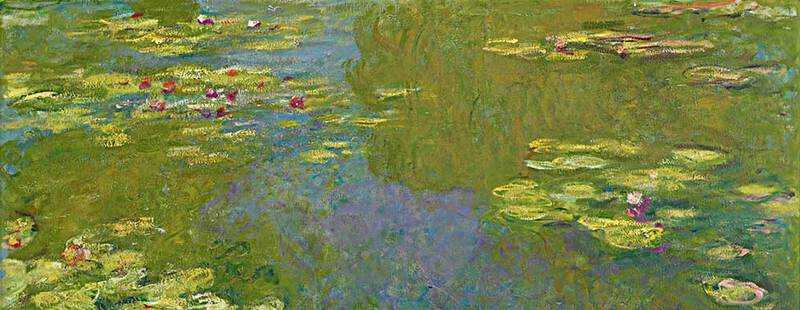

The Water Lilies, paintings of Monet's garden at his home in Giverny, are the most famous impressionist works.

Giverny

Monet moved to Giverny, a small town 50 miles north-west of Paris, in 1883 (the year of Manet’s death). He rented a large country house for himself, his two sons, Alice Hoschedé (the wife of Ernest, a Monet collector) and her six children.

Monet set about turning Giverny into both his sanctuary and the horticultural paradise that he would spend most of the next 30 years painting.

Interesting fact...

The locals were at first suspicious of this new modern painter. He must have been a sight to behold, often setting up a dozen canvasses and moving between them every few minutes to catch the light. Before long they were playing games on Monet, charging him to cross farmers’ fields and dismantling haystacks and even threatening to fell poplars as Monet was painting them.

Monet gradually won the locals over. He purchased the Giverny house in 1889, bought a field at the bottom of the garden in 1891 and set about turning it into a water garden. Soon Monet was employing a number of gardeners to tend to his personal Eden.

The Water Lily series

The Water Lily series comprises over 250 paintings, produced over 30 years from the mid-1890s. The range of paintings is remarkable:

- First, there is the diverse subject matter: there are works of whole ponds, of the Japanese bridge, of ponds and adjacent gardens, and extreme close-ups of only a few water lilies (or Nympheas)

- Second, there is the range of colours: greens, blues, yellows and aquamarines gave way to a far redder palette when Monet's eyesight deteriorated in the 1910s as he developed cataracts.

- Third, there is the range of size. The early works were typically a metre square (or thereabouts), but later on Monet produced huge canvasses (largely to donate to the French nation) which often measures 6 by 2 metres.

Monet's Grand Decorations

In 1922, Monet agreed to donate eight of his largest water lily paintings to the French state, provided that a suitable venue could be found to house them.

The negotiations were fraught: Monet made a list of unreasonable demands on the architect commissioned to design the galllery. In the end matters were resolved by the intervention of Monet's friend and former French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau.

The venue ended up being the Musee de l'Orangerie in the Tulieres gardens in Paris. Housed in two bright oval rooms on the upper floor, the paintings are individually named. They includeMorning with Willows, Tree Reflections,The Clouds and Setting Sun.

Alice Horschede

Ernest Hoschedé, a wealthy department store owner, had been a great supporter of the impressionists in general and Monet in particular since the early 1870s.

In 1876 he commissioned Monet to paint decorative panels at his country estate, the Chateau des Rottembourg. It was whilst here that Monet probably started an affair with Ernest’s wife Alice-not how you should repay your patron!

Ernest fell on hard times and was bankrupted in 1878. To economise, the Horschede and Monet families moved into a house at Vetheuil together. This unusual arrangement was made all the stranger by the fact that the Horschedes has six children.

When Monet moved to Giverny, Alice and her children followed. The children were packed off to local schools and nobody really believed that Alice was Monet’s housekeeper. Ernest visited now and again, and Monet made sure that he was away on a painting trip (though he still got extremely jealous!). And Monet and Alice married in 1892, the year after Ernest’s death.

Strange but true ...

Monet’s relationship with Alice almost certainly preceded Camille’s death and there is a fair chance than Monet fathered Alice’s final child. Later, Monet’s eldest son Jean married Alice’s eldest daughter Blanche.

A typical day at Giverny

Alice appreciated Monet’s gift and that he needed to focus on his work. She therefore ran the household with regimental efficiency. Monet would rise early and then get painting; lunch was at 11.30 on the dot so that none of the afternoon’s light got missed; and dinner parties were rare because Monet turned in early to restart the process.

Alice died in 1911, whereupon Blanche became Monet’s near invariable painting companion.

6. Haystacks, Rouen Cathedral and more ...

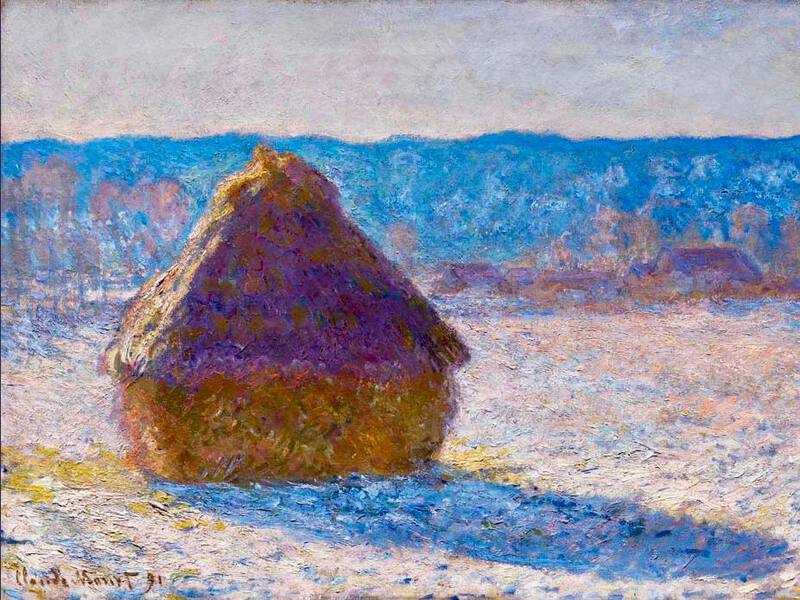

Monet is famous for a number of further series of works, including Haystacks, Rouen Cathedral and the Houses of Parliament.

The Haystacks (or Grainstacks)

Monet's 25 Haystacks, painted between 1889 and 1892, depict stacks of harvested grain in different lights and during different seasons. The 3-6 metre-high stacks in fact contained wheat and were a way of storing it until threshing machines could make their way around the countryside to separate the wheat from the chaff. Monet painted the Haystacks because he was fascinated by light. But the works were also commercially successful (a 1891 exhibition at Durand-Ruel's gallery resulted in the sale of 15 versions of the Haystacks within three days).

Rouen Cathedral

Monet's 30 versions of Rouen Cathedral, painted on-site between 1892-3 and worked on in his Giverny studio the next year, focus on the facade of this 12th century architectural masterpiece. They are painted from almost exactly the same angle, at different times of day and different points of the year. The cathedral is painted in weak morning light, shrouded in fog and in glorious sunshine. Sadly, the series was split up (there was some talk of it being acquired for the French nation).

The Houses of Parliament

Monet loved London, having spent the 1870/1 Prussian war here. He returned in 1891 and again in 1899 and 1900 to paint views of the Thames, in particular the gothic Houses of Parliament and Charing Cross Bridge. The 19 pictures of Parliament are remarkably varied: some are saturated with rich colours, whilst others show the structures lost in fog, a cloudy sky, or the sun just starting to break through. Monet typically painted from a room at the Savoy Hotel or from St Thomas' hospital.

Other series

Monet produced a number of other collections of paintings in his final decades:

Poplars: Monet painted his Poplars in the summer and autumn of 1891. They were growing on the banks of the River Epte, close to Giverny, and were painted from a moored studio-boat. At one stage, Monet had to buy a number of poplars from the Limentz commune to stop them being lopped before he had finished. This was a good investment: the striking pictures, given structure by the trunks of trees often reaching to the top edge of his canvasses, sold well.

Venice: Monet produced 37 works during his visit to Venice in 1908 (not bad for a 68-year-old!). The most famous include the luminous San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk, the Grand Canal and the Doges Palace.

Bordighera: An earlier and lesser-known trip, to the Italian town of Bordighera in 1884, produced equally dazzling results. Monet wrote to Rodin to explain that he had been

"fencing, wrestling, with the sun."

He was referring to his attempts to capture the bright Mediterranean sunlight. His most famous work from this trip, simply entitled Bordighera (pictured), is of lush green vegetation and trees in the foreground and the terracotta town and deep blue sea in the background.

7. Legacy and resources

Monet is rightly regarded as the greatest impressionist painter, for a number of reasons.

Monet's key qualities

Industry: Monet's productive period spanned about six decades. Over that time, he produced some 2,500 works (the true figure is probably higher as he destroyed a number that he deemed substandard). His output was usually of landscapes, though Monet knew how to produce a good portrait as well (we mention Woman in the Green Dress and Camille on her Deathbed above)

Beauty: Put simply, Monet's paintings are beautiful. The emotion they typically produce in the viewer is not one of awe at the technical proficiency, or intrigue at some hidden meaning, but unadulterated joy.

Popularity: Today, Monet exhibitions are big ticket or blockbuster events. And Monet works do exceptionally well at auction. Of the 20 most expensive impressionist paintings, eleven are by Monet (the others are by Cezanne, Renoir and Manet). The most expensive Monet to go under the hammer is Le Bassin aux Nymphéas, sold by Christie's London in 2008 for £40.9 million (giving it an inflation-adjusted price of $113.2 million).

Involvement: Though Manet was the first to take on the conservative art establishment, Monet was heavily involved in the impressionist movement. For instance, he exhibited at and played a large role in the organisation of the first two independent impressionist exhibitions. He also produced the painting, Impression Sunrise, that got the impressionists their name

Monet's Top 10 Paintings

Our selection of Monet's Top 10 Paintings is as follows:

- The Woman in the Green Dress (1866)

- The Magpie (1869)

- The Frogpond (1869)

- Impression Sunrise (1874)

- Gare St-Lazare (1877)

- Bordighera (1883)

- Haystacks (1889-1892)

- Rouen Cathedral (1892-3)

- Houses of Parliament (1899-1900)

- Water Lilies (1889 onwards)

Resources

One of the best general introductions to impressionism is Sue Roe's The Private Lives of the Impressionists. As for Monet-specific literature, we have not found much that we would recommend. For an in-depth and meticulously researched account of how Monet produced water lilies for the French state in the early 1900s, check out Ross King's Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies.