1. Moving to Giverny

Monet’s motivations for moving to Giverny are complicated.

He wanted to find somewhere cheap where he and his sons, and his lover Alice Hoschedé and her family, could live together.

This takes a little explaining ...

Camile Doncieux and Ernest Hoschedé

Claude Monet married his first wife, Camille Doncieux, in 1870 and had two sons with her: Jean (born three years earlier, in 1867) and Michel (born in 1878).

Tragically, Camille developed pelvic cancer at about the same time Michel was born and became gravely ill. She died in September 1879.

Some time prior to this, a man called Ernest Hoschedé became one of Monet's main patrons. Amongst other things, he commissioned Monet to produce decorative panels of his drawing and dining rooms. It was during this time that Monet met Ernest's wife, Alice.

Hoschedé fell on hard times. His department store business failed and he was bankrupted. And so, to economise, the Monet and Hoschedé families decided to live together.

Curious cohabitation

The two families lived together first at Vétheuil and then at Poissy. During this time:

- Alice acted as a full-time carer to Camille.

- Monet was almost certainly conducting an affair with Alice, literally under the noses of his dying wife and Alice's husband. (It is very likely that Jean-Pierre Hoschedé, Alice's youngest child and Michel Monet’s close friend, was also his half-brother.)

- Ernest took to travelling between Paris and Vétheuil, tolerating the living situation but avoiding Monet as much as possible.

Debt

During this time, debt plagued the two families. Camille passed away in 1879 and by 1881, Monet could no longer afford the rent on the house in Vétheuil. When the landlady demanded immediate payment of all the outstanding rent, at least 18 months’ worth, the household was forced to move again - this time to Poissy.

Constant moving and fears about money put significant strain on Monet. The letters he received and sent during his stay in Etretat are evidence of the precarious situation he found himself in. He feared that if he could not find a home for him and Alice then he would lose her completely.

As he wrote in a letter to Alice:

“My eyes are swimming with tears; can it really be true? Must I get used to the idea of living without you [Alice]? […] I am so very, very sad. Nothing means anything to me anymore. I couldn’t care less if my paintings are good or bad.”

Thus, his decision to move once again, this time to Giverny, was a desperate attempt to find somewhere permanent for them to settle.

Monet stumbles across Giverny

Monet found the tiny village of Giverny almost by chance.

Hurriedly searching for somewhere suitable, and most importantly somewhere inexpensive, Monet took the train to Vernon. From this medieval village he walked and wandered and found a hamlet. One house looking away from the road and up towards the river captured his attention and he found that it was available to rent.

They moved in the following month.

2. Life at Giverny

Together with Alice, her children, and Monet’s children by Camille, the household moved to Giverny in April 1883.

The most enticing feature of the new house in Giverny was its garden. Spread over two acres, the property had orchards of fruit trees, spruce and cypress-lined pathways, surrounded by overlooking hills.

The initial design

When they first arrived, there was no whimsical planting and very little colour. Instead, the design was regimented and box hedging dominated the space. One of the first jobs was to rip out the box hedging, which both Alice and Monet hated. Then the couple set about transforming the plot into a haven of flowers, doing away with the scrubby aesthetic and most of the orchard.

Together they created a 'Clos Normand’ or a Closed Normandy flower garden, a term coined by the French gardener Georges Truffaut.

Monet's Eden

Gustave Geffroy, a friend of Monet, described his visit to the garden:

“As soon as you push the little entrance gate, on the main street of Giverny, you think, in almost all seasons, that you are entering a paradise. It is the colorful and fragrant kingdom of flowers. Each month is adorned with its flowers, from the lilacs and irises to the chrysanthemums and nasturtiums. The azaleas, the hydrangeas, the foxglove, the forget-me-nots, the violets, the sumptuous flowers and the modest ones mingle and follow one another on this ever-ready soil, wonderfully tended by experienced gardeners under the infallible eye of the master."

In a letter to Durand-Ruel, Monet described one of his motives for focussing on the garden:

"so as to harvest a few flowers to paint when the weather is bad”.

Buying the house

By November 1890, his finances had improved significantly enough so that he could afford to purchase the house at Giverny. From then on he devoted an enormous amount of energy and funds into transforming the garden.

He hired at least six gardeners and even a Japanese botanist, who travelled to France at his request in order to offer advice.

We know from records that they planted daffodils, primroses and willow herbs in the Spring. They also sowed poppies, nasturtiums and sunflowers. Monet approached the garden with a painterly gaze, focussing on layers of contrasting coloured blooms. The riotous patchwork of colour created in the garden can be seen in works like ‘Garden Path at Giverny’ from 1902.

Monet's correspondence

Monet’s letters to Alice are filled with comments on the garden that provide an insight into his fondness for Giverny. He asks,

“And the garden? Are there still flowers? I really hope there will still be chrysanthemums when I come back. If there is a risk of frost, make nice bouquets”.

He also gives instructions to care for his plants in his absences:

“The weather has turned much cooler, and you must recommend to Eugène to cover the tigridias and other things that he knows; particularly with the moon, he was afraid of frost. Advise him too, in case of heavy showers and hail (there were some here yesterday), to pull down the greenhouse covers yesterday.”

His letters offer a glimpse at Monet’s concerns for Giverny, even when he was away from the property.

Monet's Love for Giverny

From Monet’s paintings and his letters, it is immediately clear how important Giverny was to him. He dedicated extensive time, energy and resources into creating his perfect vision of a garden, which he then incorporated into his artworks. One critic quipped in 1898,

"He reads more catalogues and horticultural price lists than articles on aesthetics”.

In Monet’s paintings, we see his garden develop along with his style. From the rich still-life works inspired by his friend and gardening confidant Caillebotte, to the hazy, ethereal water lilies painted in his later life. The role of Giverny in Monet’s world is perhaps best summarised by his own words:

“Beyond painting and gardening, I am good for nothing.”

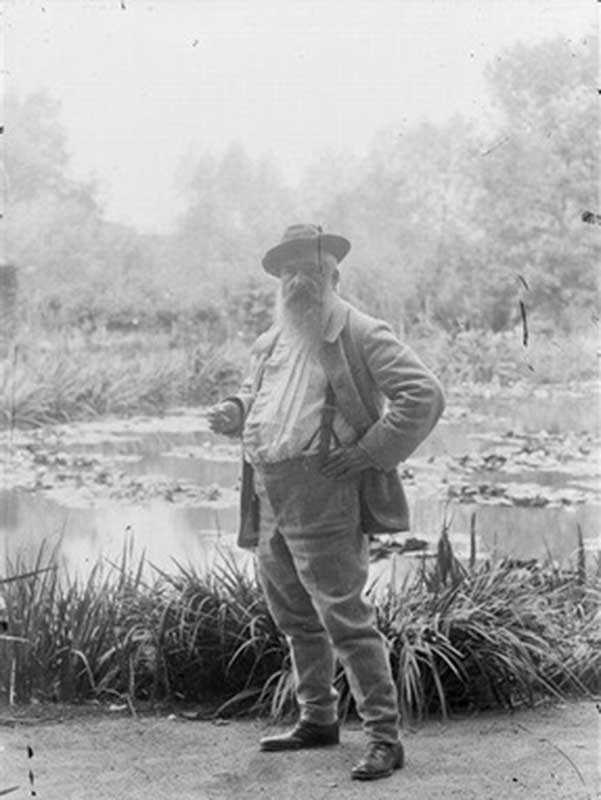

3. Monet's Water Lilies at Giverny

In his garden design, Monet drew on the English style more than the French style.

Though he followed a largely French-inspired linear design, with geometrically arranged flower beds, he opted for a flowing, lyrical form of planting that covered the beds with colour and foliage. At the same time, he was also developing an interest in Japanese garden design and water gardens in particular.

Monet's interest in Water Lilies

After visiting the 1899 Exposition Universelle in Paris, it is likely that Monet was inspired to begin experimenting with cultivating water lilies. Included in the exposition was a water garden created by Joseph Bory Latour-Marliac who specialised in breeding hardy hybrid water lilies that ranged in colours from light yellow to deep red.

Close to the house in Giverny was a marsh with a small pond. This water source, next to the river Epte, was mostly used by local farmers to water their cattle but Monet saw an opportunity to transform the plot into a water garden of his own. Already growing in the plot were wild water lilies and arrowhead so he was able to envision what it could become.

Monet therefore resolved to purchase this additional plot of land.

Logistical difficulties

Separated from the existing Giverny property by a railroad and major street, the plot presented some logistical difficulties.

This was added to by the fact that the local community took exception to Monet's plans, deliberately delaying the process in any way they could. Nonetheless, by February 1893, Monet had succeeded in purchasing a section of the land.

The locals

The next problem in Monet's vision for a Japanese water garden was the locals’ fears of exotic plants poisoning the water supply and killing their cattle. It took over three months for Monet to obtain permission to plant his water lilies.

Whilst he was away in Rouen, Monet wrote frustratedly to Alice saying,

“This enrages me and I want no longer to have anything to do with […] all those people in Giverny. There is nothing but trouble ahead, believe me, I give it up completely. Don’t rent anything, don’t order any lattice, and throw the aquatic plants in the river; they’ll grow there. I want to hear no more about it, I want to paint.”

Eventually, Monet received the permission he needed and he set about enlarging the pond. He also planted a range of water lilies in all different colours, which he purchased from Latour-Marliac.

In total, Monet extended the pond three times, tripling the size of the water garden.

The Japanese Bridge

Unlike in the Clos Normand garden, Monet drew heavily on Japanese prints as inspiration for his floating garden. He had a Japanese bridge built over the pond, mimicking the bridges from ukiyo-e prints such as ‘Wisteria at Kameido Tenjin Shrine’ (1856) by Hiroshige.

When construction of the bridge was completed, Monet painted three works depicting the structure through 1895 and even more in 1899. An exhibition at Paul Durand-Ruel’s gallery in 1900 featured 12 paintings of the bridge, largely from the same view.

Monet's industry

Overall, Monet painted over 250 canvasses centred on his water garden. The vast majority of the works focus solely on the water lilies. The others feature a wider view of the garden, including the Japanese bridge, the weeping willow trees and the collection of flowers that linked the banks of the pond, including irises, day lilies and wisteria.

As the garden matured, it became denser. Monet emphasised this feeling of crowded vegetation in his paintings, exaggerating it beyond what can be seen in photographs from the same time. As well as the plants themselves, he also accentuated their reflections in the water, creating a sense of shifting perspective.

His later paintings became even more dreamlike, gradually losing their sense of perspective altogether. Ignoring the bridge and the banks, Monet magnified the water and the water lilies, painting them in swirling colours on enormous canvasses. These final works were completed shortly before his death.

Reflecting on his water garden before he died, Monet said:

“It took me some time to understand my water-lilies. It takes more than a day to get under your skin. And then all at once, I had the revelation – how wonderful my pond was – and reached for my palette. I’ve hardly had any other subject since that moment.”

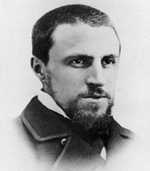

4. Monet and Caillebotte’s gardening friendship

Like Monet, Gustave Caillebotte was also a keen gardener, having purchased a house in Petit Gennevilliers in 1881.

Located in a quiet suburb set across the River Seine from Argentiul, the house was well-situated but lacked a large plot of land. To counter this problem, Gustave Caillebotte and his brother began buying up surrounding plots in order to extend their garden.

Gardening advice

Monet and Caillebotte swapped gardening advice regularly. They both worked to create dense, abundant gardens that were packed with riotous colour, which they then translated into their paintings. As well as horticultural tips, the two artists also exchanged seeds and cuttings between them.

One painting in particular, ’Dahlias, Garden at Petit Gennevilliers’ from 1893, offers an evocative image of what Caillebotte’s garden would have looked like. So too does ‘Roses, Garden at Petit Gennevilliers’ from 1886, whilst works like ‘Blue Irises, Garden at Petit Gennevilliers’ (1892) and ‘Sunflowers, Garden at Petit Gennevilliers’ hint at Caillebotte's enthusiasm for individual plants. Unfortunately, unlike Giverny, nothing remains of what he created.

In letters between them, Caillebotte discusses the details of his irrigation system and the building of his new greenhouse. There is also evidence of the strong bond they had, formed through their mutual love of gardening. For instance, in a letter of apology for cancelling their lunch, Caillebotte explains:

“I am growing a stanhopea aurea (an orchid) which has been in flower since this morning. The flowers only last three or four days, and will not bloom again for another year. I cannot let it go.”

Monet's planting patterns

Monet also plans Caillebotte’s visits around the patterns of his own garden, writing phrases such as,

“My dear friend, don’t forget to come Monday as agreed, all my irises will be in bloom, later some will be over. This is the name of the Japanese plant which I obtained from Belgium: Crythrochaete. Be sure to talk to Monsieur Godefroy about it and to give me some information about its cultivation.”

Interestingly, Caillebotte’s interest in plants in his artwork developed earlier than Monet’s. In many of Monet’s still-life works from the late 1890s, there is evidence of the influence of Caillebotte’s paintings. He clearly draws on elements of earlier works by Caillebotte, including his use of shadowy forms to represent foliage, which has the effect of making the flowers appear as though they are floating.

Caillebotte's plant paintings

Caillebotte used a range of brushstrokes to evoke the different textures of certain plants: thick, impasto for irises; short, animated flicks for chrysanthemum petals; and long, sweeping strokes for foliage. These forms inspired Monet’s later still-life paintings too. The influence is best seen in the contrast between his paintings from the 1890s compared to the more static still-life pieces from the 1870s and early 1880s.

Monet’s admiration of Caillebotte’s work was no secret. He hung Caillebotte’s ‘White and Yellow Chrysanthemums in the Garden at Petit Gennevilliers’ (1893) on the wall of his bedroom at Giverny. Caillebotte had painted the work from flowers cultivated in his garden at Petit Gennevilliers and Monet’s own series of chrysanthemum paintings clearly reflect the impact of Caillebotte’s style on his. In particular, he draws on Caillebotte’s tendency to paint the blossoms closely packed together, using a range of radiant colours.

John House, an expert on Impressionism, described Monet’s Chrysanthemum works, including ‘Bed of Chrysanthemums’ from 1897-98, as

“some of the most lavish still-lifes produced by the Impressionist group and some of the most radical challenges to a long-standing still-life tradition”.

Most notable is the way the blooms fill the canvas, hinting at the spatial experiments Monet would later employ in his later Water Lilies paintings.