1. Durand-Ruel’s early years

Paul-Marie-Joseph Durand-Ruel was born on 31st October 1831 in Paris.

His career as an art collector began with his parents, Jean Durand and Marie Ruel, who owned an art supplies and print shop. Jean met Marie when he was working as the chief assistant in the shop on Rue St Jacques. She purchased the business and they married in 1825.

Durand-Ruel's parents

Jean exhibited works by Eugene Delacroix, Jean Baptiste Camille Corot and Théodore Géricault in the shop, selling and renting pictures to his customers. Over time, the shop developed into a meeting point for artists and collectors, becoming a gallery in its own right.

As the gallery side of the business became more popular, the Durand-Ruel concept moved to a more elegant Parisian neighbourhood on the rue des Petits Champs, next to the Place Vendôme in 1839.

Jean recognised that tastes could change and with them the prices that collectors were willing to pay. He backed unpopular artists, gradually generating interest in their works and encouraging collectors to his gallery. This was undoubtedly one of the key foundations of his son’s career to follow.

Paul takes over the family business

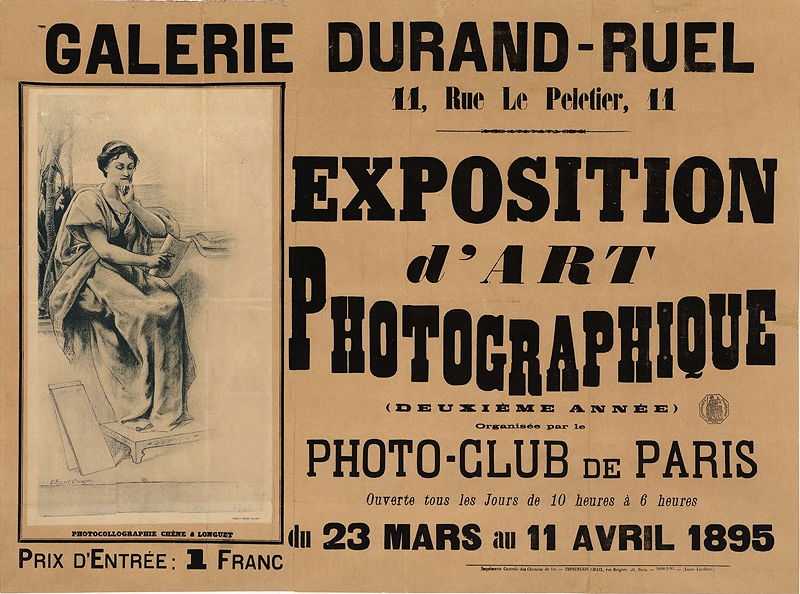

When his father passed away in 1865, Paul inherited the gallery. Though sources suggest he had originally planned to become a missionary, or join the military, he quickly established himself as a dealer and art expert in Paris. He moved the gallery to 16 rue Laffitte/ 11 rue Le Peletier, known as ‘la rue des tableaux’ or the street of pictures. This was the center of the Paris art scene.

Durand-Ruel worked to build up a network of international galleries and business contacts, seeking to promote the work of artists he respected and admired. This led Durand-Ruel down an even more adventurous path than that of his father, taking bigger gambles on as-yet unknown artists.

Personal life

As a Catholic monarchist, Durand-Ruel attended mass every morning. He married Eva Lafon in 1862 and the couple had five children together. His sons were educated at the new Jesuit school of Saint-Ignace, located on the rue de Madrid in Paris, and his daughters went to the Couvent de Roule on the Avenue Hoche.

Tragically, Eva died at the age of just 30, leaving Durand-Ruel to bring up their young children alone. He never remarried and his art dealership became the primary source of passion in his life.

2. Durand-Ruel and the Barbizon School

As an art collector, Durand-Ruel’s earliest focus was the artists associated with the Barbizon School in France.

This included now famous names like Camille Corot, Jules Dupré and Théodore Rousseau who were outsiders from the French art establishment. When his father was alive, the Durand-Ruel gallery had a strong association with many Salon artists.

To lend the Barbizon artists greater legitimacy, Paul exhibited the paintings of both schools side by side, helping to promote the Barbizon paintings in the eyes of collectors.

Out on a limb

Unafraid of stepping out on his own, Durand-Ruel was the sole dealer to purchase artworks by the Barbizon School in the early days. He used sales from the works of the Salon artists to finance this project. Later, when the Barbizon school was more established, Durand-Ruel did the same to support his purchases of Impressionist works.

In particular, Durand-Ruel was a strong supporter of Théodore Rousseau and in 1848 he bought every painting the artist had made thus far. This leap of faith was a considerable financial risk, especially when taking into consideration that the paintings did not sell for the next 20 years. He made an agreement with another dealer to raise the funds necessary for the purchase.

Nonetheless, this long-term strategy enabled Durand-Ruel to achieve enormous profits many years later. His dealings with Rousseau were indicative of his forward-thinking commercial strategy that accompanied all his art collecting and that would serve him well in his career to come.

Durand-Ruel was the principal buyer and source of emotional support to the Barbizon School from the late 1860s onwards. There is also strong evidence that Durand-Ruel was a very generous mam paying above what the artworks were worth.

Millet

He supported Jean-François Millet, one of the founders of the Barbizon school, for many years. He advanced him money and acted as the sole support for much of Millet’s career. Throughout his career he also organised loans for artists who needed them, providing funds to pay for rent, doctors fees, tailors bills and even food.

These financial considerations were the beginning of his process towards innovating art dealership, which he would hone throughout his career. The monopolisation of certain artists’ works was a deliberate strategy to raise prices and enable him to organise solo exhibitions. He also excelled at using the biography of the artist to generate interest in their works.

Art journals

Durand-Ruel recognised the need for independent art critics to offer a counter-narrative to the mainstream critical press and he established two art journals of his own ‘La Revue Internationale de L’Art et de la Curiosité’, founded in 1869 and ‘L’Art dans les deux mondes’ in 1890.

He hired writers to delve into the body of works produced by the artists he supported, encouraging the public to look at the artists in their entirety rather than just judging single pieces separately. The journals included interviews with the artists in their studios, painting an intimate picture of the individuals behind the works and cultivating their personas.

Copying Bankers and the USA

This method of promotion was borrowed from the financial world where bankers and industrialised started their own journals to promote their business practices and encourage investment. Durand-Ruel used this method to stimulate interest in untested artists and raise the prices that their artworks could be sold for.

Similarly, Durand-Ruel championed the Barbizon School in America, promoting their Realist, natural works. They became popular with an American audience and continued to sell well for many years to come. In 1885, a three-day auction of Barbizon paintings in New York sold for $406,910 in total. This showed the power of the transatlantic market and what it could mean for all of Durand-Ruel’s artists.

3. Durand-Ruel and the Impressionists

Already a keen collector of the Barbizon School, Durand-Ruel was introduced to Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro around the early 1870s when he was in London.

The three men had fled to England to escape the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war in France. In exile, Pissarro and Monet continued to paint and Durand-Ruel purchased a number of their paintings in London.

First meeting

Their initial meeting was arranged by Charles-François Daubigny of the Barbizon School. This was a turning point in Durand-Ruel’s career, creating lasting ties with some of the most prominent Impressionist artists of the movement to come.

Shortly after their initial meeting, Durand-Ruel established an exhibition featuring Monet and Pissarro’s works. The show was held, ironically, at the German Gallery on New Bond Street.

Durand-Ruel had bought his collection of Barbizon artworks with him when he fled to London. Thus, in this show of established artists including Corot, Millet and Daubigny, he also slipped in the works of Monet and Pissarro. In doing so, he leant these unknown individuals status and legitimacy.

London exhibitions

These exhibitions continued in London until 1875. Some of the works exhibited at the gallery were Monet’s ‘Green Park’ and ‘The Thames Below Westminster’, both from 1871. These dreamy, hazy works of iconic London landscapes are some of Monet’s masterpieces, perfectly capturing the city in its fog-laden beauty.

Once again, Durand-Ruel bucked convention by purchasing works by Auguste Renoir, Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas and other impressionist artists when he returned to Paris. This was a bold move at a time when most critics, dealers and collectors were highly condemnatory of the movement.

Cornering the impressionist market

Durand-Ruel’s approach to Impressionist art was novel - instead of buying a few pieces and seeing how they fared on the market, Durand-Ruel bought up large numbers of artworks within a year of meeting Impressionist artists. This was a brave approach, following his dealings with the Barbizon school but it ultimately allowed him to corner the market and establishing his position at the centre of Impressionism.

On the other hand, Durand-Ruel would often not pay for the impressionist paintings he was buying up-front. He instead doled out the price on a monthly basis.

Durand-Ruel and Manet

As well as his visionary approach to Impressionist artworks, Durand-Ruel was also an extremely patient, unshakeable individual. Many of the works took between 10 to 20 years to be sold as the market was highly resistant to the Impressionist style. This did not stop him. He bought 23 paintings from Édouard Manet on the first day they met in 1872.

Before then, Manet’s works had barely sold at all. Durand-Ruel spent the next 30 years selling pieces gradually as collectors emerged. Some of these works are now extremely well-known including ‘Moonlight at the Port of Boulogne’ from 1868 and ‘The Battle of the U.S.S. Kearsarge and the C.S.S. Alabama’ from 1864.

Durand-Ruel the counsellor

Another important aspect of Durand-Ruel’s approach to business was his sensitivity and generosity, often at his own expense. A series of letters between the dealer and Monet demonstrate this nurturing relationship. Monet despairs at his paintings of the Norman coast, stating that he has plans to destroy the canvasses.

In response, Durand-Ruel begs Monet

“Please don't do that. I'll send you money. Just send me the canvases in return.”

He offered emotional support to the struggling Impressionist artists, acting as a voice of encouragement even while the French art establishment was shunning their works.

Too much power?

On the other hand, accounts from the time suggest that some artists were uncomfortable with Durand-Ruel’s power and his monopoly of their works. Concerns were raised by Pissarro and Sisley in particular. Similarly, the fiercely independent and wealthy Mary Cassatt was also less wedded to Durand-Ruel’s methods than many other Impressionists.

Introducing the impressionists to the USA

In 1886, Durand-Ruel travelled to New York City to exhibit the works in his collection at the National Academy of Design. He was invited by James Sutton, the director of the American Art Association, and Durand-Ruel negotiated for the Art Association to pay for the shipping, advertising, exhibition and insurance expenses in their entirety. He could not speak English but in New York he sold paintings that had taken over 20 years to be recognised in France.

The show was a roaring success with the 300-strong collection selling out almost completely in a few weeks. The response from the American market was so impressive that Durand-Ruel decided to establish a branch of his art dealership in New York. He opened a gallery on Fifth Avenue in 1887.

This was instrumental in introducing Impressionist art to a wider North American audience, further promoting the movement and shaping the artistic legacy that it holds today.

The fervour created by the American show also spurred interest in Europe with more European collectors approaching Durand-Ruel to purchase Impressionist works. The fallout from this exhibition enabled the Impressionist artists to finally achieve financial security, driving up the prices of their works from 50 francs to 50,000 francs in some cases. Similarly, Durand-Ruel was able to pay off all his remaining debts.

Financial success and security could have dampened the enthusiasm of some of the impressionists. But Monet used the cash to buy and then enlarge the property he had been renting in Giverny, engage gardeners, and continue painting water lilies for another three and a half decades.

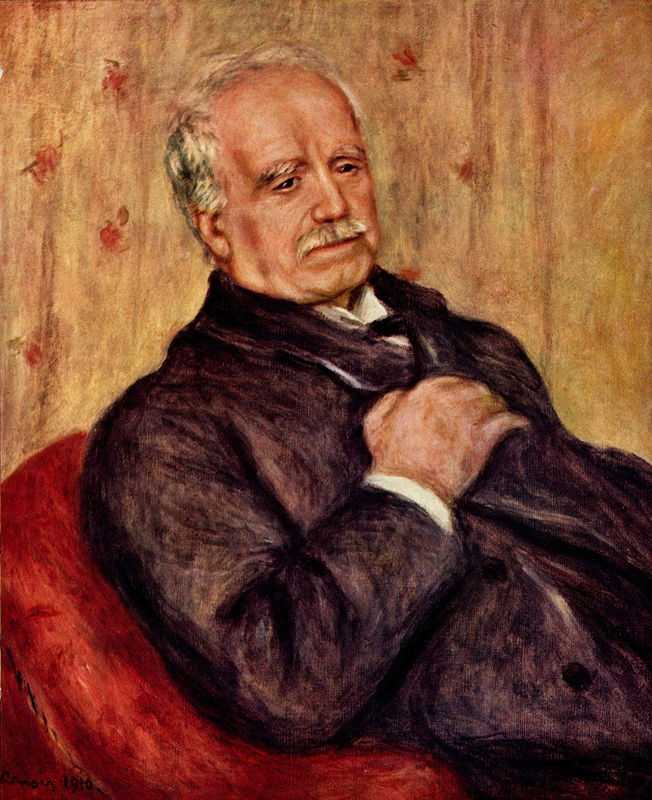

4. Portraits of Durand-Ruel

One of the Impressionist artists closest to Durand-Ruel during his long career was Renoir. Indeed, Renoir painted the artist and his family several times.

‘The Daughters of Paul Durand Ruel (Marie Theresa and Jeanne) from 1882 is a glowing and happy portrait of his two daughters seated in a sun-kissed garden setting. The dappled light and vibrant colour palette is indicative of Renoir’s painting style during the later 1870s.

Other portraits include one of Durand-Ruel’s oldest son, Joseph, and a portrait of his younger sons, Charles and Georges. His three sons followed him into the art business and Charles eventually ran the New York branch of the Durand-Ruel empire.

Durand-Ruel’s most important portrait was a solo painting created by Renoir when he was already 69 years old. The elderly gentleman is seated, looking at ease and enjoying his success after many decades of hard work and precipitous risk. The portrait is understated but affectionate, reflecting Renoir’s friendship with Durand-Ruel.

Many of these portraits were hung in Durand-Ruel’s Parisian home, which also functioned as a gallery space. He would admit people to visit his home and allow them to view the works by Renoir, Monet and others displayed there.

In doing so, he presented the paintings of his artists as they would appear in a bourgeois setting, cementing their validity in the minds of potential buyers.

5. Durand-Ruel’s legacy

There can be no doubt that Durand-Ruel was a focussed and intelligent businessman. The small stationary shop owned by Jean and Marie grew to become one of Europe’s most prestigious art galleries, the Galerie Durand-Ruel.

As a supporter of the Barbizon School and the impressionist movement, Durand-Ruel was a key figure in the continuation and rise of both movements.

He bought over 5,000 Impressionist artworks in total including some 1,000 Monets, 1,500 Renoirs, 800 Pissarros, 400 Sisleys, 400 Cassatts, and about 200 Manets. His fearlessness and determination, as well as his foresight, meant that he became the principal agent for Impressionism and a key vehicle for the success of its artwork.

Durand-Ruel devised creative solutions to market resistance and unceasingly sought to promote the Impressionist movement in every way possible. One of the pioneers of contemporary art dealers, he innovated in merging the economics and fashion of art in Paris. He promoted solo exhibitions, free and open access to exhibitions and created a global brand.

By the time of his death Durand-Ruel had branches of his dealership in London, New York, Paris and Brussels. He received the Légion d’Honneur on 5th February 1922. This recognition by the French state was not received for his contribution to art but to foreign trade.

He died in 1922 at the age of 89. The words spoken very to his death perfectly summarise the life of this extraordinary individual:

"At last the impressionist masters triumphed […] My madness had been wisdom. To think that, had I passed away at 60, I would have died debt-ridden and bankrupt, surrounded by a wealth of underrated treasures.”

Instead, Durand-Ruel became the most important and successful dealer of both the Barbizon School and the impressionist movement, helping to grow and promote key artists and change artistic tastes forever.

!['Woman Ironing', by Edgar Degas, begun c. 1876, completed c. 1887, purchased by Georges Durand-Ruel [1866-1931]. The painting probably remained in the Durand-Ruel family collection from Georges' death in 1931 until at least 1947, when it was exhibited at the Durand-Ruel Gallery in New York.](/static/1bafd3fb6d779387840160602fb90e8e/aabdf/durand-ruel-edgar-degas-woman-ironing.jpg)