1. Courbet’s early life

The artistic career of young Courbet appears to have come about through sheer determination.

He was largely self-taught, following his own rigorous and thorough schedule in order to learn how to paint like the Old Masters of European art.

Courbet chose not to enrol in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts or to learn to paint under any of the great classical artists of the period. Instead, he preferred to pursue his own form of artistic education, spending hours on end in the Musée du Louvre.

Courbet's childhood

Growing up in the small town of Ornans, near the French Alps, Gustave had an idyllic childhood. Born in 1819, he was the eldest child and only son. His family was supportive and close and he spent most of his time with his school friends and sisters, outdoors and in nature.

His father, Eléonor-Régis, was a wealthy farmer and landowner with large estates in the Franche-Comté region of east France. He encouraged his children to appreciate the natural world, following the Courbet family tradition as wine growers and farmers in the area.

Régis was also creative and eccentric, spending much of his time inventing new methods of farming and technological innovations. By all accounts, his inventions were very poor. His local nickname was ‘cudot’, a word in the dialect of the region to describe someone with pipe dreams.

His mother, Sylvie, had family in the law profession, including a Professor of Law based in Paris. Gustave received some training in pre-law but decided to pursue drawing and painting instead.

Courbet's early works

There is evidence to suggest his entire reason for going to Paris to study law was merely a pretext for him to pursue his dream of becoming an artist, which he had been moving towards since childhood. No matter how hard his father tried to dissuade him, Courbet found a way to do what he wanted.

Sylvie ran the farm and kept the family afloat, organising Régis and minimising the fallout from his failed inventions. She also played the flute and encouraged musicality in her children. Gustave painted his younger sisters often, including in ‘Young Women from the Village’ from 1852. Of his three sisters, Zélie played the guitar and Juliette played the piano. Zoé is also featured in the painting.

Much to Courbet’s dismay, this painting was heavily criticised by the Salon in 1852 whose panel stated that it was tasteless and “ridiculous”. This was partly due to the traditional perspective of the painting and the innocent country scene it depicted. One critic called the landscape attractive but said that the figures were vulgar and ugly, whilst deriding the diminutive size of the cows in the scene.

Art historians have stated that Gustave’s upbringing made him a man of the soil, giving him determination and robustness but also a certain ‘roughness of character’. This interpretation can perhaps best be explained by his first painting accepted by the Paris Salon in 1844. This was a self-portrait titled ‘Courbet with a black dog’ from 1842.

This naturalistic work showed the artist in a rocky landscape, wearing the clothes of a traveller complete with a walking cane. At the same time, Courbet presents a somewhat contradictory image. Though he is dressed in rural clothing, his expression is haughty and superior, even while his surroundings suggest a vagrant lifestyle.

The influence of his parents and his upbringing can perhaps explain this unusual work. His mother’s teaching gave him a certain thoughtfulness and sensitivity but from his father he inherited pride and the endless pursuit of glory. These traits would reveal themselves repeatedly throughout his artistic career and shape his legacy.

2. Courbet and Realism

Moving to Paris in 1839, Courbet ignored his father’s plans for his career and chose instead to follow a bohemian lifestyle.

He began studying in lesser-known artist’s studios and dedicated himself to painting and repainting works of the Old Masters, focussing on Rembrandt in particular.

Delacroix

Like so many artists around this period, Courbet was heavily inspired by Eugène Delacroix. Delacroix experimented with optical illusions in his artworks. He played with simultaneous contrast, building up layers of complementary colours to lend his paintings greater vibrancy and drama. Delacroix’s studies of colour would also go on to inspire the Impressionists and Neo-Impressionism in particular.

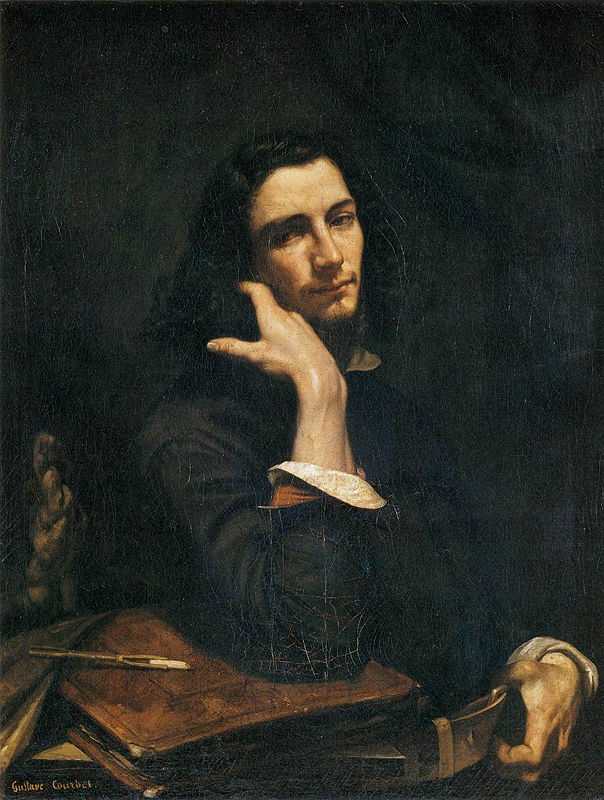

The Desperate Man

At first, Courbet’s paintings adhered to Romantic ideals. ‘The Desperate Man’ from 1843-45 is a classically Romantic self-portrait, typifying the Romantic image of the struggling artist.

Courbet stares out at the viewer with wild eyes, grabbing at his hair with his hands. The painting is thick with emotion and Courbet portrays himself as a strangled, feverous animal. However, it should be noted that this is also a very flattering portrait of the young man and he bristles with masculinity and passion.

This was one of a number of self-portraits Courbet undertook during the 1840s. In later paintings such a ‘Man with a pipe’ from 1848, the image is far softer and the Romantic tropes are heightened further.

Courbet presents himself as a mysterious, poetic character who appears to have been taken directly from a Romantic novel or verse of poetry. These self-conscious portrayals can be understood as Courbet attempting to find his place in the artistic community of Paris, even as he faced rejection from the mainstream art establishment.

Stonebreakers and Burial at Ornan

Perhaps it is no surprise then that Courbet would radically shift towards Realist styles in the years after this work was completed. Whilst visiting his family in Ornans the following year, Courbet painted two of his best known paintings that would come to define his career - ’The Stonebreakers’ in 1849 and ‘Burial at Ornan’ in 1850. These paintings depict ordinary peasants and labourers in a highly realistic way.

The first thing that strikes the viewer of ‘Burial at Ornan’ is that it is enormous. The figures gathered at the funeral are life-size. They are imposing and raw. These works portrayed the emotions and hardships of the lower classes, dramatically breaking with Romantic conventions from the time. The peasants are not venerated in any way; the depiction is gritty and dark. Hence, these works marked the start of Courbet’s journey into Realism.

The Artist's Studio

One of the best examples of Courbet’s Realist painting came later in the 1855 work ’The Artist’s Studio’. This cinematic painting depicts a busy studio complete with a nude model draped in cloth and a landscape painter, Courbet himself, in the centre of the throng.

According to Courbet’s own interpretation, on the right of the composition are the “friends and art lovers” and on the left is “everyday life” with a priest, a beggar and an unemployed worker included in the mass of figures.

The enormous scale of ‘The Artist’s Studio’ echoes the grandness of history paintings. However, Courbet plays with the subject matter, placing the artist as the central hero in the scene.

This painting was rejected by the Universal Exhibition in 1855 and so Courbet organised his own exhibition in a site nearby, separate from the official event. Here he showed forty works under the banner of ‘Realism’. Though it was unsuccessful, this event demonstrated Courbet’s courage and irreverence, as well as foreshadowing the Impressionist Exhibitions to come.

Which branch of Realism?

At the end of the 19th century, Realism had spawned several different schools of thought, each of which had their own effect on art and politics. These can be divided into different sub-categories with different interpretations of the central ‘Realist’ theme.

The first was the Classical or Academic position that sought to reflect the world as idealised and picturesque, removing controversy and ugliness from portrayals of the world.

In contrast, the Romantic position sought to represent feelings and emotion, championing individuals and extremes. On the other hand, the basic Realist aesthetic was to show life in all its variability, ugliness and contradictions. This form sought to represent reality in a way that included death, illness and ageing. The final school of thought relied on light and optical fact. It was this aspect of the movement that would give rise to the Impressionists.

3. Courbet and the Impressionists

Courbet, along with his contemporaries like Camille_Corot" Corot and the Barbizon School, exchanged radical ideas that paved the way for the impressionist movement.

The impressionists embraced the concept of realism and objective observation of the everyday world, moving away from the historical painting of earlier eras of French art.

Optical Fact

A key concept in realist art at the turn of the 19th century was the prioritising of ‘optical fact’. This led to an emphasis on light and colour - the way in which different light levels and natural light in particular can affect the optical reality of the world around us.

This was where painting ‘en plein air’ became important. The only way to portray true reality or optical facts was to observe and capture them as they happened in the natural world.

In Courbet’s paintings, depictions of the natural world were largely centred on the Franche-Comté region of France where he grew up. However, in 1865, he began a series of paintings on the other side of the country in the Normandy region. These were his most important works in relation to the Impressionist movement.

Seascapes

The paintings Courbet produced in Normandy were seascapes, capturing the changing skies and varying currents of the coast. The end result was a stunning collection of sensitive, emotive paintings that perfectly rendered the differences in light and form of the coastal landscape.

The series portrays the seas of the English Channel at different times of the day, some with towering grey waves and others with blushing pink skies.

There can be no doubt that these seascapes inspired Impressionist artists who sought to capture a fleeting moment in time, whilst privileging light and colour over form. The paintings themselves demonstrated Courbet’s inventive, spirited style, thick with impasto paint that made the physical works as dynamic as the seas they were based on.

Realism vs Impressionism

Whilst Courbet’s work was a key starting point for the Impressionists, they also diverged from his Realism in many ways. Taking Monet’s work as a key example, the artist moved from attempting to capture ordinary life in its immediate image moved towards an ever more abstracted and transitory reality.

His scenes of lakes covered in lilies, complete with wealthy French patrons enjoying their leisure time, gradually transitioned into blurs of reflections and colours on the water. These later images rejected form of any kind but ultimately came to represent the Impressionist movement.

Of course, Moneti s just one example of the Impressionist movement. Other artists followed Courbet’s example more closely, favouring Realist styles throughout their career. These artists included Gustave Caillebotte and Edgar Degas.

Similarly, Henri Fantin-Latour was a student of Courbet for a short time in 1861, though ultimately his style of realism was more discreet than Courbet’s and the two artists parted ways.

Beyond impressionism

Similarly, the neo-impressionists adopted scientific techniques in their form of impressionism, moving closer towards an objective reality that championed the importance of optical blending and human perception of colour.

Conversely, their paintings also became more abstracted in the process. The Pointillist techniques of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac comprised of hundreds of tiny dots of colour which built up the image, eventually these gave way to looser and more garish paintings as the movement developed.

One of the most important aspects of the Impressionist movement was the artists’ attempts to capture natural light and the variations therein. They were fascinated by light and colour, seeking to champion this aspect of their paintings above all else. It was this concept, partly inspired by Courbet, that saw the movement move towards abstraction as their subjects became ‘dematerialised’.

4. Courbet’s legacy

Courbet’s colourful life came to an abrupt end in 1877. He died in Switzerland, succumbing to liver disease caused by heavy drinking.

Exile

Whilst he continued to paint until the end of his life, Courbet lived in exile, unable to return to France.

His exile was rooted in political shifts in his home country. After the Prussian War and the fall of the French Empire, communists seized control of Paris and established the 'Paris Commune'. Courbet was named chairman of its Republican Arts Commission.

During his tenure, the Place Vendôme Column built by Napoleon I was destroyed. In a twist of politics and fate, Courbet was put on trial for the crime despite his involvement being unclear.

He was sentenced to prison for six months before being commanded to pay thousands for the replacement of the column. Unable to find the necessary funds, Courbet fled the country.

Legacy

This abrupt ending was the final tragic act in a life filled with drama and ostentatiousness. Throughout his career, Courbet was a larger-than-life figure, known for his grand shows of ego and his continual courtship of outrage.

In 1870, Courbet was award the Legion d’Honneur. He turned it down. He accompanied his rejection with an open letter asserting that

“Honor is neither in a title nor in a ribbon, it is in actions and the motivations for those actions. Respect for oneself and for one's ideas constitutes the greater part of it. I do myself honour by staying true to my lifelong principles.”

In spite of his theatrics, Courbet’s art speaks for itself. In many ways, he paved the way for the impressionist movement and the post-impressionism that followed, championing realism, depictions of ordinary life and immediacy.

Courbet also went on to inspire artists in Russia, Belgium and Germany. At the same time, his public disdain for the Paris Salon and the wider French art establishment served as an example for later artists desperate to break away from the strict conventions imposed on them.

This legacy did not go unnoticed by the impressionists to come.