1. Manet's early years

Manet was not academic: at school he achieved average grades in everything except art and gymnastics.

This displeased his father, who wanted his eldest son to follow him into the law.

Manet’s artistic desires were instead encouraged by his mother, with whom he was very close, and his maternal uncle, Édmond Fournier (who often took Manet and his best friend, Antonin Proust, to the Louvre).

The navy?

Manet’s refusal to study law led to arguments with his father and, eventually, a compromise by which it was agreed that Manet would become a naval officer.

But the 16 year-old Manet failed his naval exams and ended up on a merchant ship, called Havre et Guadeloupe, bound for Rio de Janeiro (8 December 1848 to 13 June 1849). The idea was that Manet would study for his re-sits on board.

Interesting fact...

The crossing was eventful. Manet was tossed around the ship during storms; spent days watching the water and the clouds; engaged in a maritime ritual for sailors passing the equator for the first time; went to the Rio carnival; was bitten by a snake; drew caricatures (which the ship's captain used as Christmas presents); and gave the crew painting lessons. He also resolved not to be a sailor.

On his return, Manet duly failed his re-sits and was eventually allowed to enrol in a painting school run by the classical landscapist Thomas Couture.

Couture's studio

Manet spent six years at Couture’s, between 1850 and 1856. Over this period he copied old masters and started to develop his unique technique. He respected Couture, who encouraged his students to develop their own style.

Did you know?

On occasion Manet and Couture quarrelled. Once, Manet stormed out of Couture’s studio in protest about a critical remark and refused to return for a month!

After leaving Couture’s in 1856, aged 24, Manet opened his own studio and after a few years produced his first major work: the Absinthe Drinker. It is a grand painting depicting a poor Parisian drunkard. And it was Manet’s first submission to the annual Salon (Exhibition) organised by the influential Academy des Beaux Arts (Fine Arts Academy).

The Salon

In a time where there were few private exhibitions, the Salon was critical to the success or failure of an aspiring artist. Acceptance by the jury and positive reviews in the papers would lead to commissions and sales. Rejection or negative commentary could stop a career in its tracks.

The 1859 jury did not take to The Absinthe Drinker, which received the approval of only one the twelve jurors (that of the romantic painter Eugène Delacroix).

When Manet turned to Couture for comfort he got none. Couture remarked that:

“the only drunk around here is you!"

2. The 1860s

The 1860s started well for Manet: he won an honourable mention in the 1861 Salon.

But things went downhill from there. His entries for the 1863 and 1865 Salons attracted downright hostility. By 1867, he was so desperate to show his works that he paid for the construction of his own pavilion so that his works could be seen by the worldwide audience attending the World Exhibition in Paris.

The 1861 Salon: signs of promise

For the 1861 Salon, Manet submitted two works: an unsentimental portrait of his parents (Portrait of Monsieur and Madame Monet), and The Spanish Singer.

The former shows his father looking stern and authoritative, though it was actually produced the year after he had suffered a severe stroke. The latter, of a slightly gormless looking street entertainer, won an honourable mention—probably because Spanish subjects were fashionable at the time.

Manet was not to receive any further praise from the jury for another two decades.

The 1863 Salon: Luncheon on the Grass

Manet tried again in 1863, this time with a painting called Le Dejeuner sur l'herbe (Luncheon on the Grass).

Even to a modern eye, this is an unusual work: the foreground shows two well-dressed Parisian men eating a picnic with a naked female. A partially dressed woman bathes in the mid-ground. And the four figures are pictured under a coarsely painted tree canopy.

Interesting fact...

To the Salon’s jury, however, Luncheon on the Grass was an abomination. They were used to historical, mythological and religious scenes. Some still life might occasionally be acceptable, though even this was considered second-rate. But modern scenes of dandies (fashionable young men) and perhaps even prostitutes were beyond the pale. The jury rejected the work.

The Salon des Refuses

Manet then had a stroke of luck.

The jury for the 1863 Salon was particularly harsh, rejecting two-thirds of the works that had been submitted. News of discontent amongst artists reached Emperor Napoleon III who, sensing a political opportunity, declared that an Exhibition of the Refused should be held so that the public could judge the rejected art for itself.

The public attended the “Salon des Refuses” in their droves. But they came to be entertained and not to admire. Manet’s painting was singled out for particular ridicule, with critics questioning whether it had been painted with a mop and whether the work was Manet’s idea of a practical joke.

The stinging criticism might have knocked a lesser man but Manet would not back down. He even revelled in his notoriety. And he remarked to a friend:

“if they want a nude, I’ll give them a nude.”

He was planning perhaps the most controversial painting of all time: Olympia.

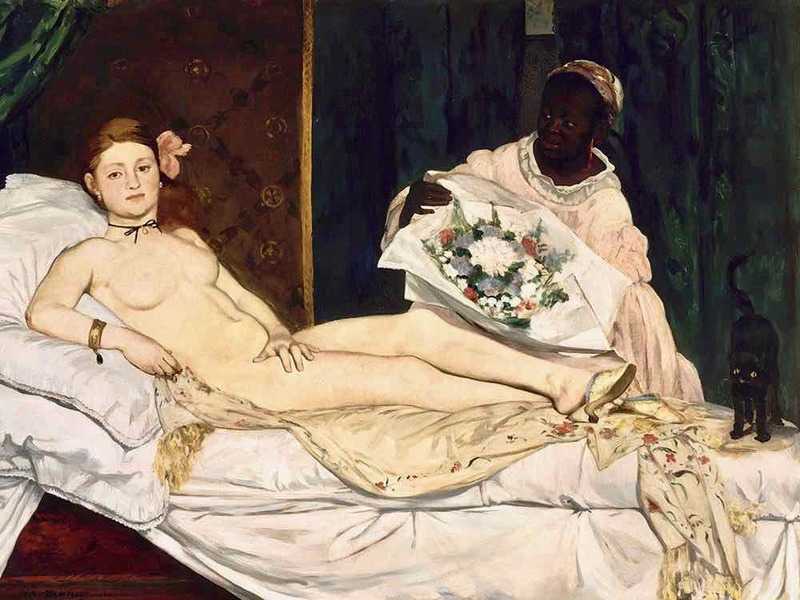

The 1865 Salon: Olympia

Olympia features a Parisian prostitute on her bed staring unapologetically at the viewer.

There can be no doubt about her profession: (i) the name Olympia was associated with courtesans; (ii) so too were black cats (see the far right of the picture); (iii) Olympia wears a provocative black necklace; and (iv) Olympia's maid appears to be bringing her a bouquet from a satisfied customer.

In fact, the real surprise is that Olympia was accepted by the jury for the 1865 Salon. Perhaps they thought that the criticism Manet would inevitably receive would chasten the young man.

Reaction to Olympia

The public were shocked and the critics harsh. The Salon’s organisers even had to protect the painting from being slashed or punctured be offended viewers. As for the papers, one wrote

“never has a painting received more laughter, mockery and catcalls”.

Another said Olympia resembled a female gorilla. A lot of the criticism was hypocritical: at this time many aristocratic men visited prostitutes on a regular basis.

Manet complained that

“insults are beating down on me like hail”

and travelled to Spain to escape.

But Olympia was not all bad: Manet had shown that he was willing to stand up to the establishment, which encouraged the other impressionists to do likewise; and now everybody in Paris knew his name.

Dejuner sur l'herbe and Olympia feature in our selection of the best 10 impressionist paintings.

1867: Manet’s own pavilion

In 1867, Manet received a double rejection: from the Salon’s jury and from another jury formed to select works for the 1867 World Exhibition being held in Paris.

His reaction was to build his own pavilion, at a cost of 17,000 francs (advanced by his mother) to display his major works. He even penned an emollient foreword to his exhibition catalogue. But few came, and even fewer came to admire.

The foreword was Manet's attempt at conciliation with the conservative art establishment. He said this:

"The artist today is not saying 'Come and see my faultless work' but 'Come and see my sincere work'. ... Monsieur Manet has never wished to protest. Rather, people have protested against him. ... Monsieur Manet presumes neither to overthrow earlier painting nor to remake it. He has merely tried to be himself."

The venture was a failure in financial terms. The most that can be said about it is that it solidified Manet’s position as the leader of the impressionists, a man who was happy not to conform.

The Execution of Maximilian

Manet could not help being controversial.

He was an opponent of Napoleon III and, when his puppet ruler of Mexico, Emperor Maximilian, was executed and the French 'empire' of Mexico collapsed he could not help but produce a painting recording events.

In total, Manet produced three large canvasses and a smaller study.

- The earliest work relied on press reports and is historically inaccurate (for instance, the firing squad are shown wearing sombreros).

- The second and third (pictured) are more accurate, depicting Maximilian and two of his highest-ranking officers (Generals Miguel Miramón and Tomás Mejía), six members of the firing squad and their sergeant (who, no doubt deliberately, resembles Napoleon III).

- All owe their inspiration to Goya's The Third of May, a painting of Spanish civilians being shot by French soldiers in 1808.

The second work was cut up (probably by both Manet and by his relatives after his death), reassembled by Degas, and now hangs in London's National Gallery.

Since criticism of Napoleon was not allowed, Manet could not exhibit the paintings in France (though one of the large canvasses appeared in America) and Manet was refused permission to make lithographs of them.

3. Manet's personal life

Manet's personal life was anything but straightforward.

There was the illegitimate son born when Manet was 20 to his piano teacher, whose existence was kept secret from Manet's father; there was his public personality: urbane, witty and fashionable; and there was his love for Berthe Morisot and almost certainly lots of other women in addition to his homely wife Suzanne Leenhoff.

Leon and Suzanne

Manet struck up a relationship with Suzanne Leenhoff in about 1851. Suzanne was a young Dutch girl hired by Manet’s father to teach him and his younger brother the piano. By 1852 Suzanne was pregnant, with Leon born early the next year.

There is little doubt that Leon was Manet’s son, though Manet does not appear on Leon’s birth certificate and paternity was not expressly acknowledged during Manet’s lifetime. The evidence is compelling:

- Leon appeared in a number of Manet’s paintings (The Fifer is pictured, but also Luncheon in the Studio, Soap Bubbles and Boy Carrying a Sword),

- Leon lived with Manet and Suzanne after they married in 1862 (the year following Manet’s father’s death), and

- Leon was the main beneficiary of Manet’s will.

Interesting fact...

As for Suzanne, she was an unlikely companion for Manet. He was wealthy, witty, and enjoyed the latest fashions and cafe culture. Suzanne was plain in both looks and personality. It may be that Manet, who had a number of affairs over the years, found her presence grounding given his turbulent public life—for there is no doubt the two had genuine affection for each other.

Cafe culture

Manet loved Paris and going to its cafes.

He adored people, people watching, debating political and artistic ideas, and making people laugh. The impressionists frequented two cafes in particular: the Cafe Guerbois and later the Cafe Nouvelle Athens.

It was here that a number of the members of the impressionist circle could be found in the early evening. In addition to Manet, they included Renoir and Degas (and sometimes Monet), and writers such as Emile Zola.

Berthe Morisot

The Manet and Morisot families were in the same social stratosphere. The matriarchs of both families got on. And Manet was taken with the intellect and looks of the Morisot’s elder daughter, Berthe.

The two became very close in the late 1860s and beyond, though how close remains debatable.

Interesting fact...

Manet appears to have fallen in love with Berthe, and certain of her correspondence appears incriminating (whilst many letters written by Berthe to her sister, Edma, were destroyed at Berthe’s request).

Ultimately, Manet’s way of moving on was to engineer Berthe’s marriage to his younger brother Eugene, which took place after an on/off courtship in 1872.

Over this period Manet repeatedly painted Berthe. The results were sometimes flattering, sometimes not, and on one occasion unusual and indeed sensual (Berthe is captured lying provocatively on a feinting couch in Berthe Morisot Reclining).

4. The 1870s

The 1870s was a varied decade for Manet

He duelled with a friend and art critic; he joined the army and defended Paris from the Russians in late 1870-early 1871; he had his most popular success with Le Bon Bock (the Good Beer); and he painted some of his best art, including the Masked Ball and Nana, provoking outrage amongst critics and being yet again rejected by the Salon's conservative jury.

Duel with Duranty

Strange as it may sound, Manet duelled with an art critic friend of his, Louis Edmond Duranty, in February 1870.

Interesting fact...

The altercation started when Duranty penned an ambiguous review of Manet's submissions to the Salon that year. Manet was furious: if he couldn't count on his friends to write positive reviews, the impressionists had no chance. He burst into the Cafe Guerbois, slapped Duranty, and demanded a sword-duel.

It took place the next day, in the Forest of Saint-Germain. Neither man was adept at fencing. And after Manet managed to wound Duranty in the upper chest, the duellers' 'seconds' (ie the men who would take their place in the event of injury) declared that honour had been satisfied.

Manet and Duranty became friends again before too long.

The Siege of Paris

In late 1870, Napoleon III embarked on a misconceived military campaign against the Prussians.

The ill-equipped French forces were soon defeated and Paris surrounded. But the proud Parisians would not give up their city without a fight. They barricaded themselves in.

Did you know?

Not everyone stayed. Whilst Manet refused to leave, and indeed joined the army, other impressionist colleagues were not so patriotic. (Cezanne refused to be conscripted and hid from the authorities in a fishing village near Aix in southern France; and Monet, Sisley and Pissarro moved to London.) In contrast, Renoir was conscripted (though he did not see action) and Bazille was killed in battle.

The Prussians were supremely confident, joking that:

"The Parisians won't last a week without their cafe au laits!"

How wrong they were: Paris lasted over four months before she eventually surrendered (between 19 September 1870 and 28 January 1871). All faced hardship (even the elephants at the zoo were slaughtered for meat) and many died of starvation, disease or from the incessant shelling.

Manet, having done his duty, went to the seaside town of Archachon, near Bordeaux, to recuperate.

The 1873 Salon: The Good Beer

For the 1873 Salon, Manet submitted a portrait of a working class Parisian man smoking his pipe and enjoying his beer.

Called Le Bon Bock (The Good Beer) Manet for once judged the mood of the jury and the public.

The work was seen as an icon of solidity and solidarity in the uncertain times following the disastrous Prussian war and the fall of the Third Empire. Soon, it started appearing all over Paris, including in gift shops and as the name of a pub.

Manet also managed to make a rare sale, to the opera singer Jean-Baptiste Faure for the very considerable sum of 5,000 francs.

1874: Manet paints with Monet

Manet had been seen as the leader of the impressionists from the mid-1860s. He stood up to the establishment, socialised with and was admired by the rest of the group, and often doled out money when needed.

Manet was initially reluctant to paint en plein air (outdoors): even though his works use broad strokes, he was a perfectionist (often requiring models to sit on scores of occasions for a single work). But Berthe Morisot persuaded him to give it a go and in 1874, Manet painted with Renoir and Monet at the latter’s house in Argenteuil.

Interesting fact...

The result was that Manet’s paintings became lighter and brighter, though he did not abandon his use of black (a colour eschewed by the other impressionists). Indeed, some of Manet’s open air paintings bear a striking resemblance to Monet’s works.

Despite this pollination, and his financial and pastoral support for the group, Manet never exhibited at the eight independent impressionist exhibitions held in and after 1874. He instead continued to challenge the Salon’s jury.

1874: Masked Ball at the Opera

The 1873 success enjoyed by Manet turned out to be an aberration: the next year the jury rejected one of his most important works, Masked Ball at the Opera.

True it is that Manet was, through this painting, having a dig at the establishment. The masked ball was a high society occasion of low morals: it was attended by actresses, showgirls and courtesans. The jury probably worried that they would be identified among the male revellers (who in fact are modelled on Manet himself and his friends).

But the work is an absolute masterpiece. It has the shimmering black of top hats and dinner jackets; it evokes feelings of movement and merriment (even debauchery); it uses splashes of bright colour; and it has the usual tongue-in-cheek finishing touches (see the stockinged legs hanging from the balcony).

1876: Manet’s own show

Manet’s two submissions for the 1876 Salon were once again rejected. One member of the jury is reported to have said:

“we have given Manet a decade to turn over a new leaf, but he refuses to do so. In fact, he grows worse”.

The offending works were The Laundry (a heart-warming work of a mother and daughter sorting washing in the garden) and The Artist (a portrait of the Bohemian Gilbert Marcellin Desboutin).

Manet’s reaction was different from before: he decided to stage his own exhibition at his studio. Formal invitations were sent with the motto

“Make it truthful and let them say what they like.”

Four thousand people came. But only a few minds were changed.

One of the few was Mary Laurent, a famous actress, who became close friends with Manet and posed for a number of his paintings.

1877: the Nana scandal

In 1877, Manet returned to the subject of prostitution.

His work, Nana, depicts a famous grand-cocotte, Henriette Hauser, in a corset and petticoat looking at the viewer. She is in her boudoir applying make-up. The painting is life-sized and all the more shocking because Henriette was the mistress of the Prince of Orange (a principality in southern France).

Debating point....

Though not as brazen as Olympia, Nana is in no way apologetic. She is seemingly getting ready for a night out and ignoring a well-dressed gentleman—her client?— sat on the painting’s far right.

After its rejection by the jury, Nana was displayed in the window of an art dealer, Giroux, in the Boulevard de Capucines. Hundreds flocked to see it and the police were called when it looked like a riot would break out.

5. The 1880s

Manet died in 1883, but not before he had won a medal at the Salon, received an honour from the French state and exhibited one of his most important and puzzling works: the Bar at the Folies Bergere.

The 1881 Salon: recognition at last

Manet did not exhibit at the impressionist exhibitions because he craved official recognition. He wanted to take on and beat the art establishment; and he wanted, almost two decades after his father’s death, to justify his controversial career choice.

Recognition finally came in the form of a second class medal awarded by the 1881 jury, for a portrait of a previously exiled revolutionary called Henri Rochefort. Eight other second class medals were awarded, with no entry considered first class material.

The award also allowed Manet's boyhood friend, Antonin Proust, to award him the legion d’honneur in December 1881. By this stage Proust was minister for fine arts. The award came just in time: the government fell months later and Proust lost his position!

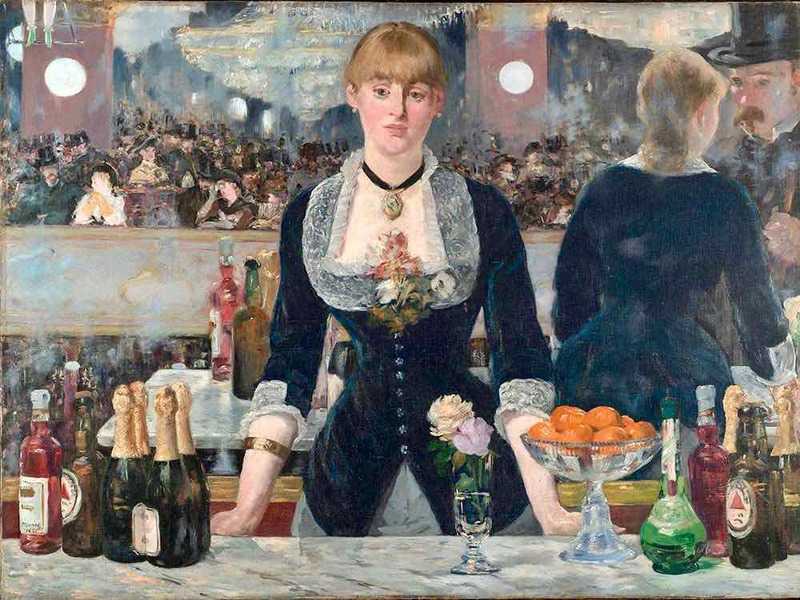

The 1882 Salon: the Folies Bergere

Normal service was resumed in the 1872 when Manet submitted the Bar at the Folies Bergere to the Salon.

This was his last major work and is classic Manet: predominantly a portrait, it shows electric lighting and one of the hottest new nightspots in his beloved Paris, with bright colours, broad brush strokes and a dollop of enigma.

The thing that confounded critics and the public at the time and still puzzles is the reflection of the barmaid, Suzon, in the large mirror found behind the bar. It seems to defy the laws of physics!

But it was quite intentional and Manet’s way of being controversial and introducing the top-hatted gentleman in seemingly intense conversation with Suzon.

Interesting fact...

Who is the man in the Folies Bergere: a patron, lover, disapproving father or someone else entirely?

The Folies Bergere was painted from a specially constructed bar in Manet’s studio. He was, by 1882, too ill to travel to the bar for sittings.

1883: Manet’s last illness

By the time he submitted the Folies Bergere, Manet’s health was failing.

Though he had denied it for a number of years, he had tertiary syphilis that was robbing him of his motor skills. The regimens prescribed by his doctors, which mainly involved bathing in spas, had not worked. And by late 1882 he was struggling to walk. He painted still lifes—mainly flowers—in his last months, socialised and read books to take his mind off the pain.

In the end, his left foot became gangrenous and his left leg was amputated below the knee. He struggled on for another fortnight, dying on 30 April 1883 aged 51.

Manet’s pallbearers included Monet, the critic and writer Émile Zola and Manet's lifelong friend Antonin Proust.

Following the procession, Edgar Degas was heard to remark:

“he was even greater than we thought."

6. Manet's Legacy

Manet was in many ways the leader of the impressionists.

Manet's legacy

He showed them how to believe in their new ways of painting in the face of official opposition and ridicule from the critics. It helped that Manet was slightly older than most of the others; that he was independently wealthy and so able to provide financial support when times got tough; and that he was fashionable, urbane and witty.

Manet's own output is unique. It plays with colour, perspective and the laws of physics. It challenges social conventions. Many of his works—for instance Dejuner Sur l'Herbe, Olympia, and the Bar at the Folies Bergere—are world famous today.

Indeed, most experts agree that Olympia was the first true work of modern art.

The slow road to recognition

In the year after his death, a Manet retrospective was held at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris.

Then, in 1890, Monet organised a public collection to acquire Olympia from Manet's widow Suzanne. That was no mean feat: Monet sent scores of letters to obtain donations of almost 20,000 francs; and then had to enter into correspondence and meetings with the authorities to decide where Olympia would be displayed.

It was not allowed to enter the Louvre immediately, being hung in the Musee du Luxembourg between 1890 and 1907, when it was finally hung at the home of French art. Olympia is now to be found at the Musee d'Orsay.

The most expensive Manets

These days, most Manets are held in the world's leading art museums. But they occasionally come up for auction.

In 2014, his Springtime (Le Printemps, 1881) was sold by Christie's in New York for $65.1 million. The previous best price, $33.1 million achieved by Sotheby's in London in 2010, was for Manet's Self Portrait with a Palette.

These two works are, respectively, the eighth and tenth most expensive impressionist paintings ever sold. But they languish far behind the sale value of works by Cezanne, Monet and Degas.

Top 10 Manet paintings

Here's our selection of the top 10 Manet paintings:

- Music in the Tuileries

- Dejeuner sur l'Herbe

- Olympia

- The Railway

- The Execution of Maximilian

- Masked Ball at the Opera

- Berthe Morisot Reclining

- Nana

- Printemps (Spring)

- Bar at the Folies Bergere

Was Manet an impressionist?

Now here is a difficult question to answer. It is fair to say that Manet did not usually paint outside and that he shunned the impressionist exhibitions.

On the other hand, he painted modern scenes with broad unblended brush strokes, two of the hallmarks of impressionist painting. And he may not have exhibited at the impressionist exhibitions but he gave his friends the courage to take on the establishment and supported them with friendship, encouragement and by doling out money when times got tough.

So our answer to the question 'was Manet an impressionist' is a resounding 'yes'!

Manet resources

The best stand-alone volume on Edouard Manet is Beth Archer Brombert's 'Edouard Manet: Rebel in a Frock Coat' (1996, 528 pages). This in-depth and beautifully written biography captures Manet's varied and complicated life. For a shorter and more general introduction to the impressionists, we suggest Sue Roe's 'The Private Lives of the Impressionists' (2006, 368 pages).