1. The Degas Debate

Much like the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition, the planning for the Seventh Impressionist Exhibition began with a debate surrounding Degas.

The discussion centred on whether or not Degas’s preferred group of artists should be allowed to exhibit with the Impressionists; a name that came up numerous times was realist artist Jean-François Raffaëlli, who had dominated the previous two exhibitions.

Caillebotte's frustration

In a letter to Camille Pissarro, Gustave Caillebotte described his struggle to convince the stubborn Degas to follow the group’s sole request: that only Impressionist artists be allowed to exhibit at the Seventh Impressionist Exhibition.

Caillebotte wrote with frustration of how:

“Degas won’t give up Raffaëlli for the simple reason that he is asked to, and he’ll do it all the less, the more he is asked to do so.”

In other words, Degas was - not for the first time - being a difficult bugger.

Gaugin backs Caillebotte

Pissarro, who had previously gone along with Degas' demands, subsequently wrote to Paul Gauguin to inform him of the dilemma.

Gauguin, perhaps to Pissarro’s surprise, agreed with Caillebotte. He confessed:

“Last night Degas told me in anger that he would hand in his resignation rather than send Raffaëlli away. If I examine calmly your situation after ten years during which you undertook to organise these exhibitions, I immediately perceive that the number of impressionists has progressed, their talent increased, their influence too. Yet on Degas’ side - and thanks only to his volition - the tendency has been getting worse and worse: each year another impressionist has left and been replaced by nullities and pupils of the Ecole. Two more years and you will be left alone in the midst of these schemers of the worst kind.”

In this letter, Gaugin also submitted his resignation to Pissarro, firmly stating that he could not “continue to serve as buffoon for M. Raffaëlli and company.”

Gaugin signed off by noting that Armand Guillaumin felt the same way.

Pissarro in a Pickle

Pissarro was left with a dilemma.

The state of Degas’ position meant that vital Impressionists were leaving the group at an alarmingly increasing rate. If Pissarro continued to remain loyal to Degas, he would be left as the sole Impressionist, potentially along with Berthe Morisot, though her position had not yet been made clear.

Paul Cézanne, Sisley, Renoir, Monet, Caillebotte, Gauguin and potentially Guillaumin had all been pushed out by Degas and his followers.

Pissarro therefore decided to follow Gauguin’s advice and agree with Caillebotte that only Impressionists should be allowed to exhibit.

2. Organising the Seventh Impressionist Exhibition

After the decision had been made to ignore Degas’ demands, the artists moved quickly to organise the Seventh Impressionist Exhibition.

Caillebotte proposed a new exhibition featuring Pissarro, Monet, Renoir, Cézanne, Sisley, Morisot, Gauguin and himself.

He also suggested they include Mary Cassatt, if she would agree to exhibit without Degas.

Gauguin's Encouragement

Gauguin continued to support Pissarro in his decision, perhaps because the good-hearted Pissarro felt a sense of betrayal in his decision to leave behind Degas.

In another letter to him, Gauguin wrote, “You will say that […] I want to hurry things, but you will nevertheless have to admit that in all this my calculations were correct.”

He went on to say,

“Nobody will ever convince me that, for Degas, Raffaëlli is merely a pretext for a break; that man […] destroys everything. Think about it all and let’s act. I entreat you.”

Getting Morisot on-side

Following Gauguin’s advice, Pissarro went to visit Morisot to invite her to exhibit with the group once again. Incidentally, Morisot was in Nice at the time, so she was received by her brother-in-law, Édouard Manet.

In a letter written to Morisot, Manet revealed,

“I have just been visited by that difficult fellow Pissarro who talked to me about your next exhibition; those gentlemen do not give the impression of being of one mind. Gauguin plays the dictator, Sisley […] would like to know what Monet is to do. As for Renoir, he hasn’t yet returned to Paris.”

Caillebotte received a similar impression to the one summarised by Manet - his letters to Monet and Renoir suggest that he was not sure that he could count on them to commit to the exhibition.

The individual who stepped in to help at this uncertain time was Paul Durand-Ruel.

Durand-Ruel

In 1882, Durand-Ruel was the only dealer embedded in the affairs of the Impressionists and he was as irritated by the disputes as Caillebotte.

He had a vested interest in organising a joint exhibition to help him to sell some of the many artworks he had amassed over the years. The financial crash in 1882 had left a number of his wealthy investors bankrupted, including his friend and key benefactor Jules Feder, which placed a great deal of pressure on Durand-Ruel to pay back his debts.

As a result, Durand-Ruel wrote to Monet and Renoir himself in order to force their hand. Renoir agreed to follow Durand-Ruel’s advice but was disinclined to have anything to do with the other artists. This was partly because plans for the show had already been put into place without his input and he had been excluded from the previous three exhibitions as a result of his participation in the Salon.

Monet and Renoir

It appeared that Monet and Renoir were both of the same mind - they disapproved of the so-called ‘Indépendants’, distrusted Gauguin and Pissarro and refused to exhibit with any artists who were not from the original Impressionist group, excluding Caillebotte who Monet was indebted to.

On the other hand, both artists were well aware of what they owed to Durand-Ruel. Durand-Ruel had been the sole supporter of the Impressionists for many years and had personally kept Monet afloat during his darkest moments, so both artists felt that a compromise must be reached.

Consequently, Renoir and Monet both agreed to take part in the exhibition, though not without plenty of to-ing and fro-ing.

Indeed, Monet received a pleading letter from Pissarro stating,

"We barely have time left. Please reply immediately if you are joining us. […] For Durand-Ruel as well as us this exhibition is a necessity. […] We owe him so much that we can’t refuse him this satisfaction. Sisley absolutely agrees with me”.

Monet replied that he would only accept if Renoir was also willing.

Logistics

Once the list of artists had finally been agreed upon, Caillebotte and Pissarro began working feverishly to bring the Seventh Impressionist Exhibition to fruition:

- The exhibition date was set for 1st March 1882, in a studio located at 251 rue St.-Honoré. This space had been organised by Henri Rouart and it was large and bright, perfect for the exhibition they hoped to stage.

- The catalogue, in contrast with that of previous exhibitions, was an amateur, hand-written document.

- This did not stop the crowds from coming. Records suggest that about 1,900 attended on the first day, with about 350 per day attending for the rest of the month (the exhibition closed on 31 March 1882).

3. The Artists

After an exhausting run-in to the 7th Impressionist Exhibition, Caillebotte, Pissarro and Durand-Ruel were successful in convincing a number of the original Impressionist artists to exhibit.

Among them were Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Pissarro, Caillebotte, Morisot, Gauillaumin, Victor Vignon, and Gauguin.

Vital statistics

In total, nine artists showed 203 works:

- Pissarro showed 25 oil paintings and 11 gouache works, including Study of a Washerwoman and Young Peasant Woman Drinking her Coffee.

- Monet exhibited 35 paintings, including Sunset on the Seine, Winter Effect, and Debacles.

- Renoir submitted 25 works. They included The Luncheon of the Boating Party, one of Renoir's most famous and enduring works, Two Sisters (On the Terrace) and Jugglers at the Cirque Fernando.

- Sisley sent 27 works, including Saint-Mammes, Cloudy Weather, which Pissarro described as “canvasses of a very British savouriness.”

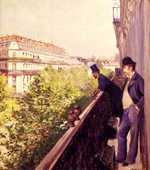

- Morisot had a more modest contribution of just nine paintings, Gauguin had 13 (including At the Window, Still Life) and Caillebotte 17 works (including Rising Road and Balcony).

For the first time in several years, the Impressionists were able to successfully stage a show that was fully Impressionist. There were no outside artists and no last minute additions from Degas.

Pissarro wrote with happiness to Georges De Bellio, who was in Romania at the time, confiding that,

“you would have been pleased with the over-all aspect of our show, for this is the first time that we do not have any too strong strains to deplore.”

It was a triumph.

Renoir

Renoir - who had severe respiratory problems - was too ill to attend the exhibition but his paintings were there in his place. In March, he returned to Morocco, which he had fallen in love with on a previous visit, instead of making the journey to Paris.

Degas Deserts

Degas refused to exhibit with the Impressionists under the new terms. To put it bluntly, he threw his toys out of the pram.

Only Mary Cassatt and Henri Rouart chose to follow him. Rouart made the decision to stand by Degas, despite having already paid rent on the premises in which the exhibition would be held!

Cezanne

Another face missing from the Seventh Impressionist Exhibition was Cézanne.

It is likely that Durand-Ruel had not insisted on his involvement as he had with Monet and Renoir as the dealer had not shown any particular interest in Cézanne’s work to date.

However, it is also possible that Cézanne had excluded himself from the exhibition as he still held a hope that he would be included in the Salon and was not “ready” to show his works in both.

Missing Manet

Once again, Manet declined to exhibit with the group, despite the fact that he could now do so in addition to exhibiting at the Salon because Degas was no longer in control. He instead showed his Bar at the Folies Bergeres at the Salon.

There is evidence to suggest that Manet wavered in his decision. In a letter to Morisot, his brother Eugène wrote,

“Pissarro had suggested to Edouard that he take part in the exhibition. I believe he now bitterly regrets to have declined. He seems to have hesitated a good deal.”

Manet visited the exhibition once preparations were under way and wrote to Morisot, who was still travelling and had sent her works in absentia. He praised the exhibition and the artists gathered there, declaring,

“I found the whole brilliant crowd of impressionists at work hanging a great many pictures in an enormous room […] Degas remains a member, pays his subscription, but doesn’t exhibit. The association keeps the name, Indépendants, with which he adorned it”.

4. The response to the Seventh Impressionist Exhibition

Durand-Ruel had contributed the vast majority of paintings not held by the artists themselves. He was one of very few lenders listed in the exhibition catalogue.

His efforts in organising the exhibition paid off and he was able to sell a great number of the Impressionist works on display.

Positive Reviews

Similarly, the critical response was also less derisive than in previous years. There was evidence that the press was now more respectful of the works, possibly because the exhibition was being orchestrated by Durand-Ruel.

In another letter to Morisot, Eugène Manet included comments from a recent review of the exhibition,

“Théodore Duret, who knows what he’s talking about, says this year’s exhibition is the best your group has ever had. That is also my opinion.”

He further sent her a thorough review of his own, detailing for his wife the different submissions from each artist:

“Sisley is the most complete and shows great progress […] Pissarro is more uneven, however there are two or three figures of peasant women in landscapes, vastly superior to Millet in the voracity of draftsmanship and coloration. Monet has some weak things next to some excellent things […] Gauguin and Vignon are very mediocre […] Caillebotte has some figures, blue like ink, very boring, and several excellent small pastels of landscapes. Durand-Ruel is taking care of everything and seems to have worked on the press. Albert Wolff has shown and praised the exhibition to some friends; he asked for your pictures.”

And negative ones

In contrast, a review by the fabled Joris-Karl Husymans disagreed entirely with Eugène Manet’s summary. He lamented the loss of Degas and Raffaëlli, concluding,

“To thus deny admission to a group under the pretext of obtaining a greater homogeneousness of works […] one fatally arrives at monotony of subjects, uniformity of methods, and, to say it bluntly, the most complete sterility.”

He then went on to dismiss most of the artists who did take part in the exhibition, apart from Pissarro and Monet.

Interestingly and somewhat strangely, Husymans’ review of Renoir’s works was favourable except for his portraits of young women. Of those particular contributions, he wrote that, although they were

“spruce and gay, [they] do not exhale the odor of Parisian girls; they are vernal harlots freshly arrived from London.”

Clearly he had opinions that went beyond his role as an art critic!

As he had done for previous exhibitions, Jules Clarterie also wrote a review of the Seventh Impressionist Exhibition in which he poked fun at the “squabbles” of the group.

Like Husymans, Clarterie mourned the absence of Degas and Cassatt, as well as Raffaëlli, stating that “These are artists of rare talent whom the Independents will be unable to replace.”

He summarised the exhibition with a few carefully selected lines:

“[They are] people with right ideas and wrong colours. They reason well but their vision is faulty. They show the candour of children and the fervour of apostles. One might be tempted to admire them, these naifs!”

Both Paul Signac and Georges Seurat attended the Seventh Impressionist Exhibition, though they did not know each other yet. Félix Fénéon, who would go on to become an art critic and coin the term ‘Neo-Impressionism’, was also in attendance.

5. The Aftermath

The Seventh Impressionist Exhibition was a glorious return to the former days of the Impressionist Exhibitions, complete with all of the movement’s original artists, excluding Degas.

It demonstrated Pissarro and Caillebotte’s determination to see the movement succeed, whatever it took. However, it was Durand-Ruel who was largely the saving force of the exhibition. He was able to enact a plan that took control of the strong personalities in the group and bring them all together.

Cézanne had chosen not to exhibit in the Seventh Impressionist Exhibition but that same year he achieved success for the first time in submitting his works to the Salon.

This was thanks to Antoine Guillemet on the Salon jury who helped Cézanne on the pretext that he was a student of his, and thus did not need a consensus from the jury to be allowed in the show. As a result, Cézanne was listed in the catalogue as: “pupil of Guillemet”.

The Salon of 1882 - which featured Manet's Bar at the Folies Bergeres - was marked by a definite move towards brighter colours than previous years. This did not go unnoticed by a number of critics, with Edmond de Goncourt remarking,

“One thing strikes me at the Salon, that is the influence of [Johan] Jongkind. At the present, any landscape of any value derives from that painter”.

However, the true and accurate statement that should have been made, and was later pointed out by Henri Houssaye was that,

“Impressionism received every form of sarcasm when it takes the names Manet, Monet, Renoir, Caillebotte, Degas - every honour when it is called Bastien-Lepage, Duez, Gervex, Bonpard, Danton”.

He went on to list more Salon painters who were enjoying the fame that had eluded the Impressionists for so long.

That Salon artists were beginning to adopt an Impressionist palette was evidence of the spread of Impressionism’s influence. Though some critics continued to ridicule the Impressionists, even after the Seventh Impressionist Exhibition, many more wrote detailed reviews of their artworks. Moreover, buyers were beginning to show more of an interest than ever before, which promised a more fruitful year to come.