1. Degas vs Caillebotte

Caillebotte was initially the driving force behind the organising of a sixth group exhibition.

By the New Year of 1881, he was already asking around to see which artists would be willing to exhibit under the banner of the Impressionists again. However, the rest of the group was heavily resistant to the idea.

Discussions around the exhibition

When it came to the decision of which artists to invite, Caillebotte was insistent that there would be no more Realists permitted into the Impressionist exhibitions.

He was determined to enforce tighter requirements than the previous year, when Degas had included a large number of artists in the Fifth Impressionist Exhibition who were barely Impressionist at all.

In a letter to Pissarro, Caillebotte wrote,

“I ask […] that a show should be composed of all those who have contributed real interest to the subject, that is you, Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Mme Morisot, Mlle Cassatt, Cézanne, Guillaumin; if you wish, Gauguin, perhaps Cordey, and myself. That’s all, since Degas refuses to show on such a basis.”

Caillebotte could not forgive Degas for imperiously dismissing Claude Monet and Auguste Renoir from the group because they had submitted work to the Paris Salon.

He was also adamant that Jean-François Raffaëlli should not be allowed to exhibit with the Impressionists again, after he had dominated the previous exhibition with an overwhelming number of realist style paintings. One critic, Jules Claretie, in praising his work had gone so far as to state that Raffaëlli was, “no Impressionist at all.”

Pissarro's Position

However, Caillebotte was mistaken in thinking that Pissarro would be sympathetic to his opinions. Pissarro stood by his opinion of Degas:

“He’s a terrible man, but frank and loyal.”

He also reminded Caillebotte that it was Degas who had first introduced him to the Impressionist group, stating that Degas,

“brought is Mme. Cassatt, Forain and you.”

Pissarro was of the opinion that it was not necessary to pine after Renoir and Monet, he believed that the Impressionists should be a unified group of artists and he did not want to include individuals who clearly did not want to be included themselves.

The inclusion of Gaugin

Caillebotte was willing to allow Gauguin to take part in the exhibition. He had been highly praised during the Fifth Impressionist Exhibition and his work showed a faithfulness to Pissarro’s teachings and influences from Renoir’s work, which made him Impressionist enough to bear the title.

However, Gauguin also jibed at Caillebotte’s plans to include more of the original Impressionist artists, namely Monet and Alfred Sisley, joking,

“we can’t flood the place with rowing boats and endless views of Chatou.”

The constant contradictions left Caillebotte exhausted and irritated. He wrote exasperatedly that,

“It’s very naive of us to squabble over these things.”

It seemed that he was unable to organise the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition if he could not find anyone to agree with his plans. In his reply to Pissarro, he confessed,

“I don’t know what I shall do, […] I don’t believe that an exhibition is possible this year. But I certainly shan’t repeat the one held last year.”

Degas and Gaugin assume command

The primary barrier to the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition was that by this point, the group lacked cohesion and seemed to have little common ground that they could agree upon.

Eventually, Degas and Gauguin assumed control of the arrangements for the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition. They sought out an exhibition space on the boulevard des Capucines at number 35 and began making arrangements on Degas’ terms.

The exhibition was planned to take place in April 1881. Their chosen exhibition space was an annex of Nadar’s old studio, where the First Impressionist Exhibition had been held. Unlike the previous exhibition, however, they rented a collection of five smaller rooms in lieu of one large studio.

Both artists agreed that they needed to get Caillebotte back and convince him to lend his organisation skills - and funds - to the exhibition. They also had the task of inviting artists to exhibit with them. By this time, the group had fragmented and many were occupied working independently on their own projects.

The Sixth Impressionist Exhibition was titled ’6e Exposition de Peinture par…’ and the room was crowded with paintings in a mixture of Impressionist and Realist styles. They hung over 170 works in total in the small space. Once again, the building was under construction and the lighting was poor - it was just a shadow of the earlier Impressionist exhibitions.

2. The Artists and their Paintings

The Sixth Impressionist Exhibition featured work mostly by the new generation of painters associated with Degas - Charles Tillot, Gustave Vidal, Victor Vingnon, Federico Zandomeneghi and most controversially, Raffaëlli.

These artists Caillebotte described as “a fighting squadron in the great cause of realism!!!!”

Once again, Raffaëlli exhibited more paintings than anyone else in the group, a factor that did not go unnoticed. His popularity among the critics also did nothing to help his popularity among the other Impressionist artists.

Gaugin

Gauguin showed seven paintings, including a nude portrait of a girl as his most notable contribution. This painting showed an obvious progression from the soft landscapes he had displayed at the Fifth Impressionist Exhibition, which were modelled largely on Pissarro’s style. Instead, this new work was freer, painted with daubs of bright blue and yellow and featuring an exotic rug hung on the wall behind the figure. This was the first indication of what Gauguin’s style would morph into in the coming years. He also contributed two sculptures to the show.

Original group members

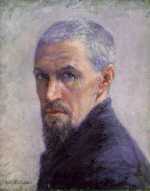

Only Morisot, Pissarro and Degas remained of the original Impressionist artists. Caillebotte declined to take part in Degas’ exhibition. Degas himself exhibited fewer than ten artworks, most of which were just sketches. Morisot also contributed only a small number of works. Pissarro was represented by 27 paintings and pastels, the largest collection from the Impressionist group and he displayed his works in frames of complimentary colours.

As in the Fifth Impressionist Exhibition, a glass case placed centre stage in the exhibition remained empty for much of the show’s opening. However, at some point, a small sculpture of a dancer was placed there. This was the long awaited sculpture by Degas that he had been working on for many months.

Degas' Dancer

The sculpture featured Marie van Goethen, a 14 year old dancer from the Opéra, posing in fourth position with one leg pointing forward.

To make the work, Degas had asked van Goethen to pose naked for him in several sessions whilst he modelled her body in extreme detail, before then posing fully clothed in her dancer’s attire.

He added the tutu and bodice on top of the body using real fabric, even modelling the dancer’s hair with human hair, possibly clipped directly from her head.

Mary Cassatt

Meanwhile, Mary Cassatt also consolidated her reputation in the Parisian art scene with her submissions to the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition. In particular, she chose to exhibit a number of works featuring children, posed in entirely natural ways. ‘Lydia Crocheting in the garden at Marly’ from 1880 and ‘The Cup of Tea’, also featuring her sister Lydia and from 1880-81, are two clear examples of the influence of the Impressionist style on Cassatt’s work.

Her bold, vigorous brushstrokes and complementary colour palette are very much in keeping with the work of her colleagues.

Much like Morisot, Cassatt focussed heavily on soft, pastel scenes often set within the home. Her portraits of Lydia reveal the everyday social rituals and pastimes of fashionable upper-middle-class women during that time, the perfect representations of the ‘Parisienne type’. ‘The Cup of Tea’ was purchased by Durand-Ruel, along with many more of Cassatt’s paintings following the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition.

3. Acclaim from the Critics

The divisions in the group did not go unnoticed by critics reviewing the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition.

Émile Zola’s deduction that the Impressionists no longer existed seemed to have some force. He questioned what would become of the original Impressionist artists, especially Monet, Renoir, Sisley and now, Caillebotte.

Recognition for Cassatt

For Cassatt, the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition brought her widespread recognition in the press. The reviews were very positive, with critics praising her portraits of Lydia, with their subtle colour palette and elegant Parisian style.

Indeed, Gustave Geffroy described one of her portraits as “exquisitely Parisian”, writing in another article that one finds “a very elegant taste of things” in Cassatt’s work.

Her paintings of children were also well received, the ever opinionated critic Joris-Karl Husymans commented, “How those portraits have made my flesh creep, time and time again” but finally he was saw,

“likenesses of enchanting tots in calm, bourgeois scenes, painted with an utterly charming, delicate tenderness.”

He further stated that she possessed a “special inherent talent” to be able to paint “French women for us” as an American.

This attention was very favourable for sales of her paintings, as described in a family letter to her brother, Aleck, describing how Mary, “has sold all her pictures or can sell them if she chooses.”

The exhibition was undoubtedly the most successful so far for Cassatt but more important than the critical acclaim was the praise she received from her colleagues whose opinions she held in high regard.

Praise for Pissarro

Pissarro was also commended for remaining faithful to the Impressionist cause. This was aided by his impressive collection of works at the exhibition, which drew the eye of anyone visiting the cramped studio space.

Husymans agreed that “One fact is dominant, the blossoming of Impressionist art which has reached maturity with M. Pissarro.” He went on to write that:

“M. Pissarro may now be classed among the number of remarkable and audacious painters we possess. If he can preserve his perceptive, delicate, and nimble eye, we shall certainly have in him the most original landscapist of our time.”

The decision to hang his paintings in coloured frames was also a novel approach that did not go unnoticed; even Jules Claretie in his column in Le Temps stated that,

“the greatest originality of these revolutionaries consists in the moldings around their pictures, which are white, gold frames having been abandoned by them.”

Though this was obviously intended as a biting critique, it did demonstrate the effectiveness of Pissarro’s plan.

Morisot is also praised

Though Morisot had contributed only a small number of paintings to the exhibition, she received the accolade from one reviewer that,

“No one represents Impressionism with more refined talent or with more authority than Morisot.”

She remained close to Renoir and Monet, despite their absence from the exhibition and wrote to them regularly.

Degas' Dancer

The highly anticipated sculpture of ‘La Petite Danseuse de Quatorze Ans’ or ‘The Little Fourteen-Year-Old Dancer’ by Degas, garnered a great deal of attention in the press.

The sculpture was simultaneously strange, intense, unsettling and difficult to ignore. Mary Cassatt’s friend Louise Elder described the sculpture as appearing as though the soul of an ancient Egyptian had entered the body of the girl, such was its eery quality.

The Paris-Journal described groups of, “male and female nihilists, fainting with rapture” at the sight of Degas’ sculpture.

Similarly, the painter Jacques-Emile Blanche recounted Whistler’s presence in the group of awestruck viewers,

“wielding a painter’s bamboo mahlstick […] emitting piercing cries; gesticulating before the glass case that contained the figuring”.

In a review of the exhibition by the Gazette des Beux-Arts, Paul Mantz praised the naturalist power of the sculpture and its lifelike pose. He described,

“the instinctive ugliness of a face upon which all vices imprint their detestable promises.”

Of course, Husymans also had his own comments for Degas’ sculpture. In his characteristically emphatic style, he asserted that,

“The fact is that with one blow, M Degas has overthrown the traditions of sculpture, just as he long since shook the conventions of painting.”

Rapture for Raffaëlli

Raffaëlli was also praised by critics and visitors to the exhibition. Albert Wolff reviewed his painting ‘Les Déclassés’ or 'the Absinthe Drinkers’ in the Figaro. The painting, which echoed Manet’s earlier work, led Wolff to state that,

“Like Millet he [Raffaëlli] is the poet of the humble. What the great master did for the fields, Raffaëlli begins to do for the modest people of Paris. He shows them as they are, more often than not stupefied by life’s hardships.”

4. The Aftermath

For Pissarro, years of faithfulness to the Impressionist cause finally paid off as he achieved recognition for his contributions to the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition.

Around this time, Paul Durand-Ruel had acquired a new source of funding from his friend, Jules Feder, the director of the Union Générale bank. This enabled him to purchase several paintings from Pissarro and support his work more regularly, providing Pissarro and his family with much needed financial relief.

Durand-Ruel gets back involved

Durand-Ruel’s financial improvements also led him to organise an independent exhibition of Impressionist work. He corralled the original Impressionists into a group, including Monet and Renoir, whose works he chose from his own extensive collections.

Monet had not submitted work to the Salon or the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition and was somewhat unwilling to help Durand-Ruel with his project.

As a result of the confident manner in which Durand-Ruel organised the exhibition, with the mindset of a dealer who needed to sell his wares rather than a group of artists trying to find an accord, this independent show was polished and cohesive.

Indeed, it was far closer to the original Impressionist exhibitions of the 1870s than the one organised by Degas and Gauguin. With his characteristic astuteness, Durand-Ruel listened to Monet and Renoir’s requests to only include the core Impressionist artists in the exhibition.

Crucially, he did not invite Degas to exhibit.

Cassatt Gains an Agent

Durand-Ruel also took on the role of Cassatt’s agent following the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition. Once Cassatt had established herself as a worthy Impressionist artist in her own right, she also began to become more involved in collecting works painted by the group.

This she did on behalf of Aleck Cassatt, shipping the paintings to Philadelphia in the U.S. Cassatt was well aware that these works, and the ones she encouraged Louise Elder to purchase, were the first of their kind in North America.

She wrote to Aleck,

“if exhibited at any of your fine art shows, they would be sure to attract attention.”

Out of the Ashes?

Thus, the Sixth Impressionist Exhibition was marked by both success and collapse. The exhibition staged by Degas had successfully served to unveil his show-stealing sculpture and given Pissarro a platform to receive well-deserved praise and recognition for his works.

However, the majority of artists who had contributed their work to Degas’ exhibition were not Impressionist at all. Many of the original Impressionists had been excluded. In contrast, Durand-Ruel’s private exhibition the same year was far more Impressionist in its contents and nature.

Both exhibitions led to new opportunities for the impressionist artists, including at a Seventh Impressionist Exhibition to be held the next year (1882).